A Study on Student Perceptions of ACPD and Changemaking

Contributing writers Olivia Fajardo ’23 and Sydney Ireland ’23 recap their study about student perceptions of the Amherst College Police Department and the effectiveness of student activism in creating change.

Police forces are endemic to college campuses: around 95 percent of institutions in the United States with at least 2,500 students have their own campus police force. Furthermore, 70 percent of universities partner with their local community police forces. That doesn’t mean those forces are popular, however. The racist histories that define colleges and police forces alike have often remained unaddressed, prompting various forms of student protests to reform campus police. Initiatives from petitions to walkouts by college students across the United States advocating for the abolition of campus police forces. Despite that effort, few colleges have followed their students’ calls— many university police forces remain on their campuses to this day.

Amherst College in particular has been called on by students in recent years to abolish their armed police force and rely on the Town of Amherst Police Department instead. Still, besides an abstract “restructuring” campaign, very few changes have been made within the Amherst College Police Department, indicating to us a lack of desire to listen to students’ voices. So we conducted research to better understand students’ views of the ACPD and student demand for change.

Our Research

As part of our psychology course, “Stereotypes and Prejudice,” we issued a survey to students about their perceptions of the ACPD and of the students’ ability to create change at Amherst. Twenty-five Amherst students participated in the study, representative of all class years and split relatively evenly across the race and gender spectrum.

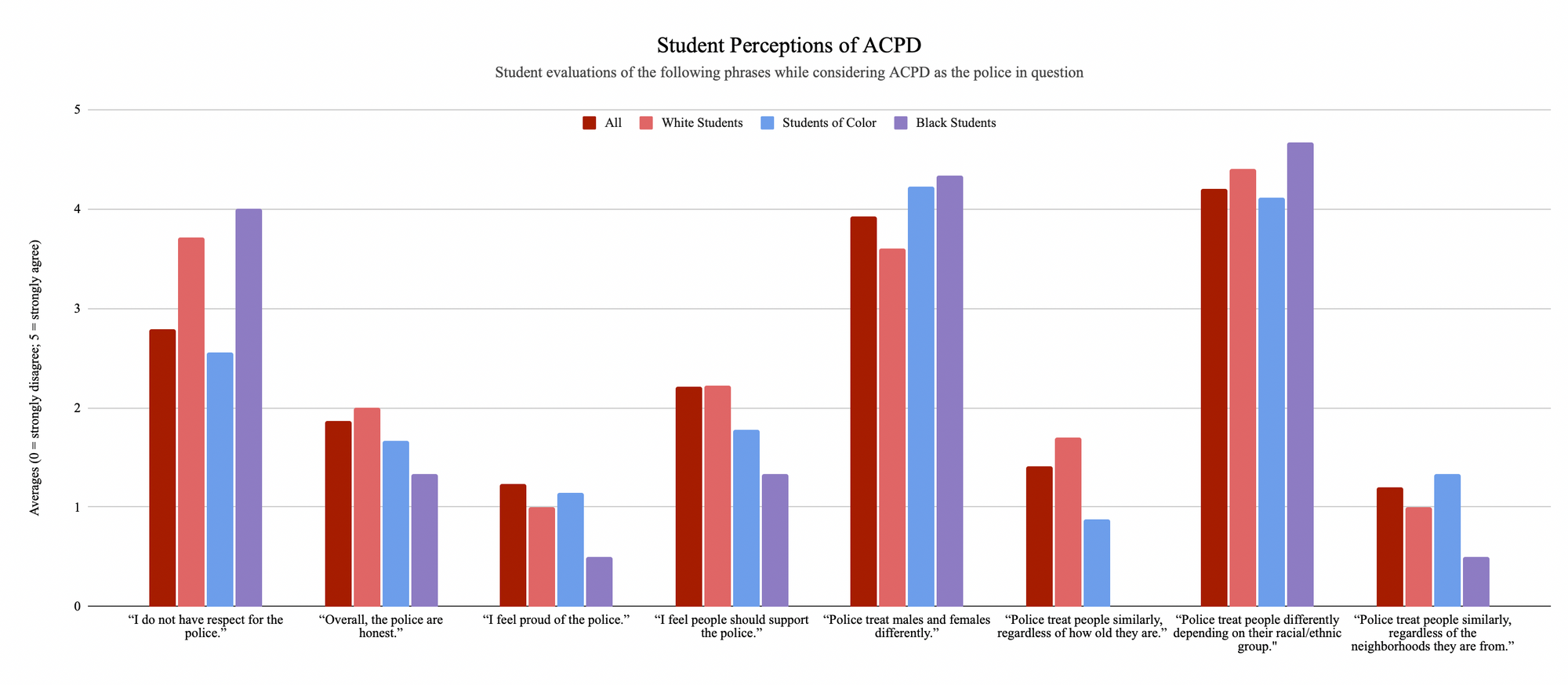

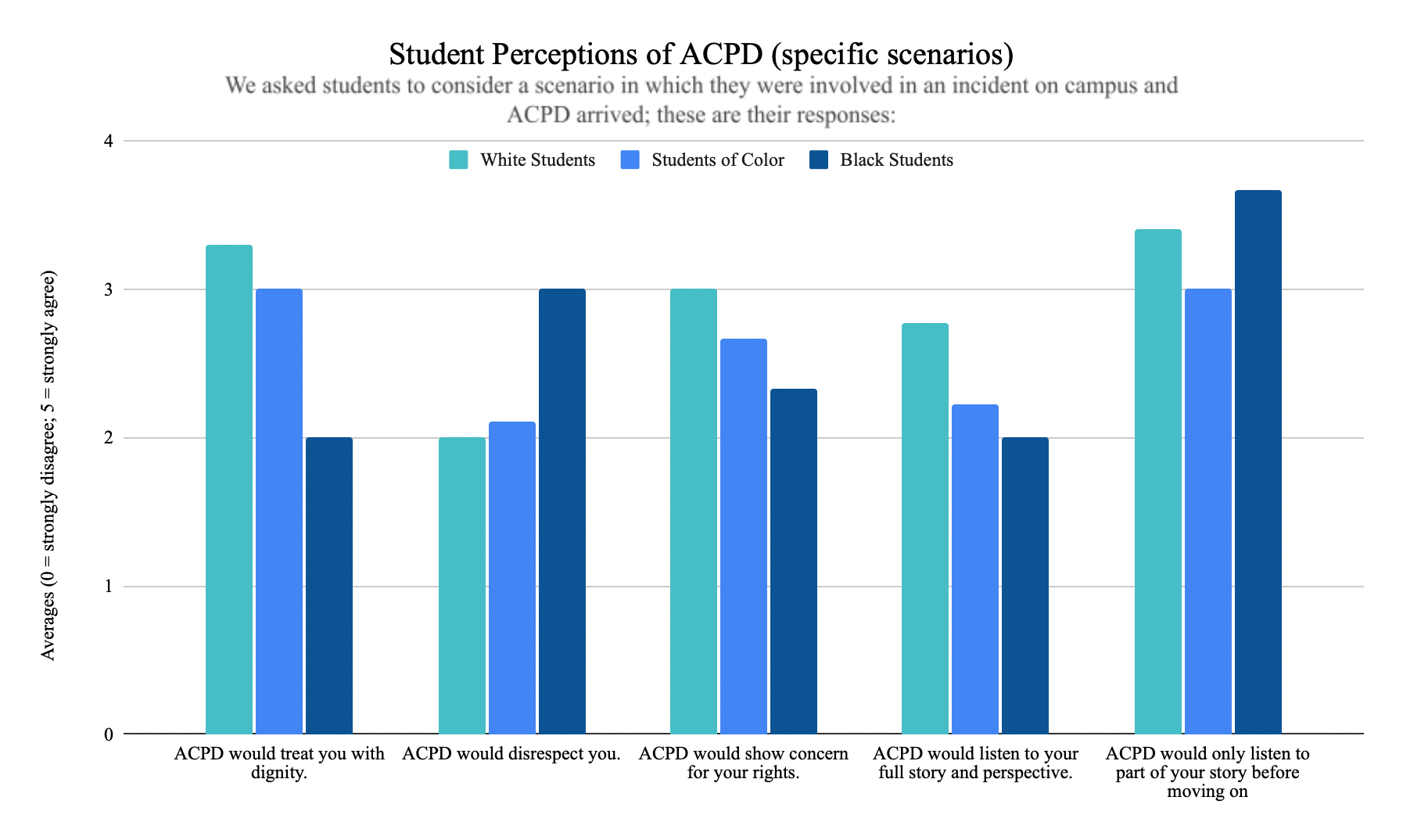

The results of this experiment indicate that Amherst students’ views on ACPD range primarily from neutral to negative (Graph A). All participants reported that they believe ACPD treats individuals of different genders, ages, and racial/ethnic groups differently. 77 percent of participants also strongly disagreed with the statement that they felt proud of the police. However, when asked to consider a scenario in which they were involved in an incident on campus, White students generally felt that ACPD would respect them while students of color were more likely to report that they felt ACPD would disrespect them (Graph B). Additionally, when asked whether ACPD would listen to their full story and perspective during this scenario, 75 percent of students of color strongly disagreed that ACPD would do so while 60 percent of White students agreed that ACPD would listen.

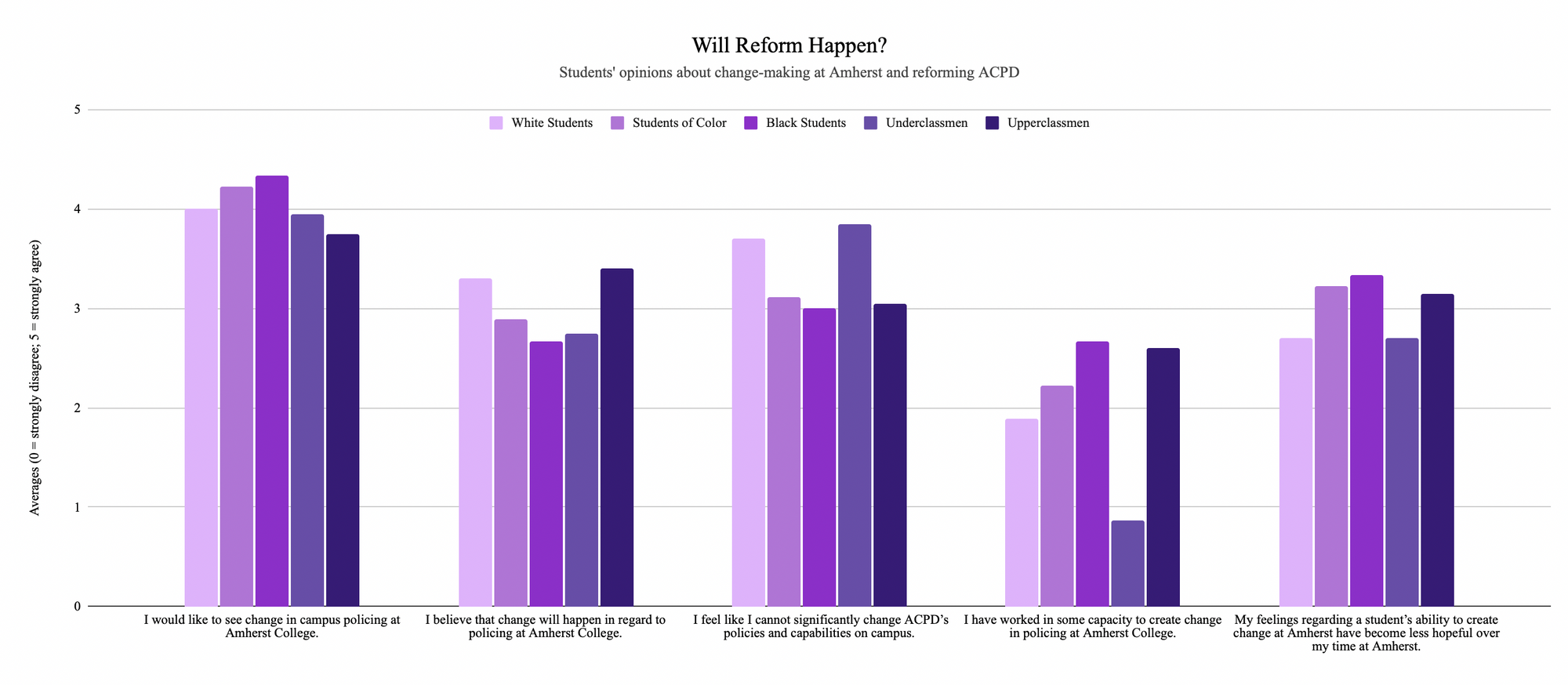

The findings of this study also suggest that students overall want to see change in Amherst’s campus policing: 85 percent of students strongly agreed that they would want to see change in campus policing at Amherst (Graph C). However, students of color were more likely to report that their feelings regarding a student’s ability to create change at Amherst have become less hopeful over their time at Amherst, with Black students specifically reporting being the least hopeful while simultaneously wanting to see this change the most. Though race was an indicator in the amount of hope a student had, there were no significant disparities in reported feelings of hope across class years.

Given these findings, we wanted to look at what Amherst College has done to support students who want to change policing, and how effective their efforts have been.

Current Efforts to Reform ACPD

We asked Suzanne Belleci, Director of the Center for Restorative Practices (CRP), to weigh in on how her office has aimed to address policing at Amherst. She stated that “Amherst College’s 19-Point Anti-Racism Plan includes an invitation for us to ‘reimagine policing,’ on campus. With that opportunity in mind, the CRP has been hosting a semester-long series of Restorative Circles.”

Restorative Circles are respectful and open spaces where community members come together to listen and converse about potentially polarizing issues. They are “rooted in Indigenous practices that center decision-making into the heart of the community,” according to the CRP’s website. Belleci explained how the Circles support the CRP’s mission: “The voices, ideas and suggested action steps are recorded and brought to the Campus Safety Advisory Committee [CSAC], who are tasked to gather information and report what they find to the college president and trustees.”

Maya Foster ’23 is a member of the CSAC and the director of the Office of Student Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. As the only Black student on the CSAC, she stated that her role in the Black Student Union (BSU) has been the most impactful position in terms of talking about campus police reform, and that the BSU has been a catalyst for change within Amherst policing. In April 2020, the BSU wrote an open letter for The Student entitled “Why We Must Integrate Amherst”. That letter followed another online letter and petition written by BSU stating a list of demands on how to proceed in addressing racism and racist actions at Amherst.

Foster believes that the college’s compulsion to create committees in response to problems is a way for the administration to avoid making substantial changes. However, Foster holds that the CSAC members are aware of this downfall and are actively trying to work against it. In response to student needs, Foster is fighting to more clearly define the purpose of ACPD so that their role is transparent to the community. She especially wants ACPD to address the negative impacts that firearms play regarding the mental well-being of Black students.

Making Change, Keeping Hope

While Foster is passionate about the crucial work that

she does at Amherst, she spoke about feeling fatigued by the amount of pro-diversity advocacy she undertakes. She stated that burnout “is definitely pretty common. I think people that pick one issue experience less burnout. Because my job is to look at equity and inclusion more holistically, it doesn’t feel like we are making as much of a difference even if we are making small, incremental changes. If you are trying to make change and you are coming from a privileged place, that change would be nice, but it’s not about your basic right to emotional or mental health and that causes much more burnout.”

Foster’s sentiments closely align with our study’s results. White students in particular experience more hopefulness in making change at Amherst while simultaneously reporting that they believe they could not significantly change ACPD’s policies and capabilities on campus, suggesting that White students see an issue but also seem to believe that the issue will fix itself without their action.

Despite these challenges, Foster is still hopeful and devoted to making change. She notes, “There have been significant changes in the structure of ACPD; they have fewer responsibilities than ever before.” While these reforms have not necessarily changed the culture of policing on campus, as the police officers are still armed, Foster is determined to continue to advocate for Black students at Amherst.

Our study shows that most Amherst students desire ACPD reform, and though White students believe change is likely, they also seem to be taking less action. These students in particular should work for the change they would like to see: attend restorative policing circles; join activist groups on campus; elevate the voices of student leaders of the ACPD reform movement, such as the BSU’s calls to action. Harness hope into actionable changemaking.

Comments ()