Bird Deaths Prompted by Collisions With Science Center Windows

A recent study by two professors at the college revealed that at least 46 birds died over a 90-day period after flying into the building’s glass edifice. The study, conducted by Professors of Biology Jill Miller and Ethan Clotfelter, has prompted the facilities department to begin further investigating bird-strikes around the science center.

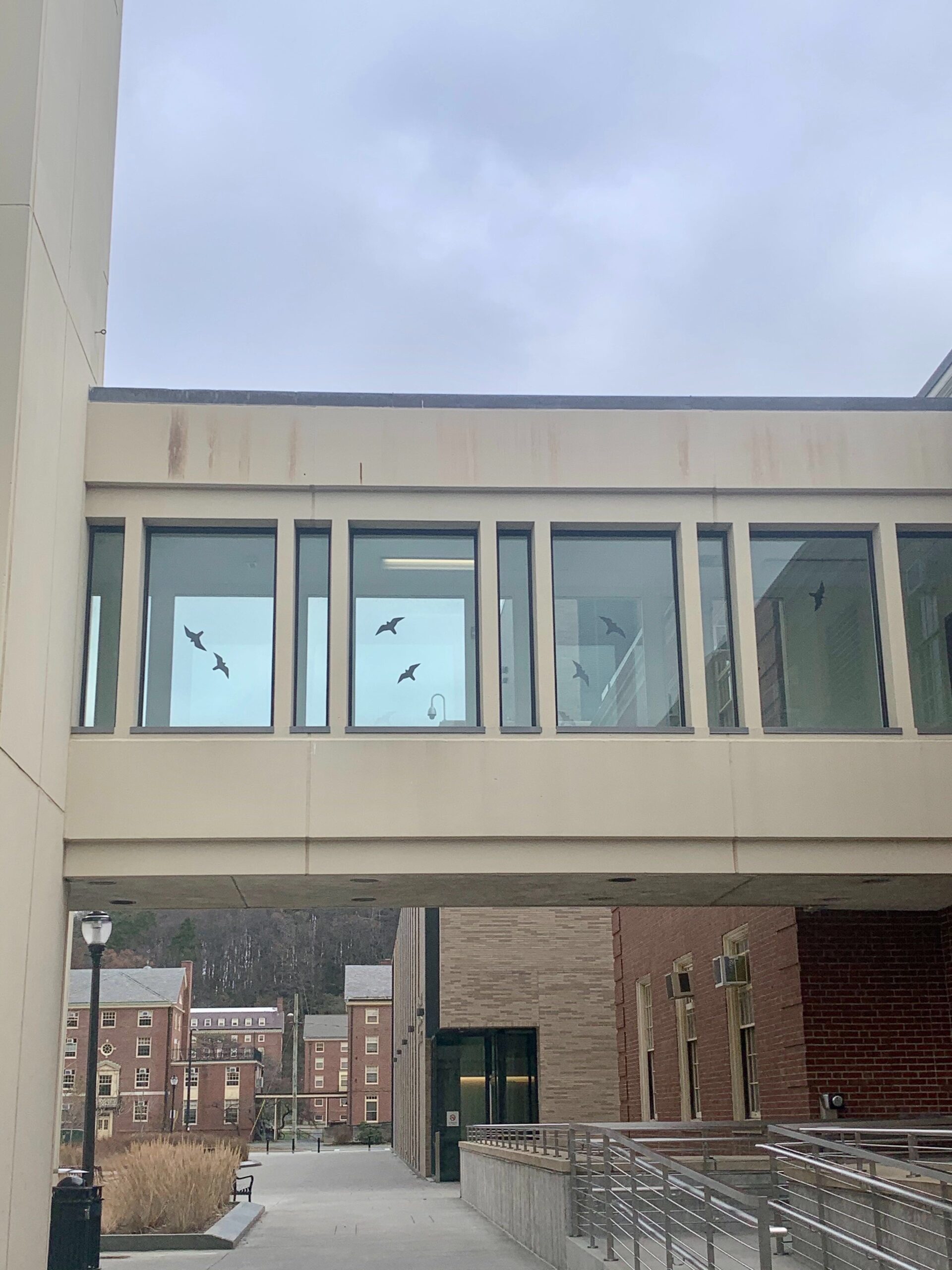

Last fall, Chief of Campus Operations Jim Brassord frequently noticed dead birds surrounding the perimeter of the science center. He worried that the building’s large glass windows were confusing birds, causing them to fatally crash into the windows. The science center, which opened in fall 2018, has multiple large windows on each side of the building, with its front face largely made of clear glazed silicone.

This trend is not isolated to the college. As universities across the country are turning to glass in constructing more environmentally sustainable buildings, many have seen similar increases in bird deaths. In 2016, students at Smith advocated for the installation of a safety net on the glass entrance of their indoor track and field building after noticing several dead waxwings around its perimeter. The University of New England saw similar waves of activism, in which students circulated a petition to amend the university’s plans for a glass building in hopes of limiting potential bird-strikes. Similar concerns about bird-strikes have been observed at other institutions including Northwestern and the University of Pennsylvania, according to a 2018 article in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

According to Miller, the bird strikes have posed a problem for a while. Miller, whose office is in the science center, often saw bird carcasses on the building’s overhangs, indicating that the birds flew into the windows above. During family weekend last fall, she noticed alarmed parents looking at the multiple dead birds surrounding the science center.

“It was embarrassing,” she said.

Brassord and Tom Davies, director of design and construction/facilities, began monitoring the bird situation at the start of September.

Facilities staff walked the perimeter of the science center three times a day and noted the position, time and frequency of the bird strikes. Brassord and Davies are collaborating with biology faculty to examine the data and brainstorm solutions.

Since September, Miller and Clotfelter have analyzed the data from the facilities team’s field work. The team collected data over a 90-day period from late July to late November. In that time frame, they found 46 dead birds. Based on the average rate of bird strikes during this time period, around 260 birds have died due to flying into the science center since the building opened.

Miller found that most of the bird strikes occur at night. She theorized that the birds may have been disoriented by the lights inside the science center, along with the transparency of the building’s glass walls. Due to the science center’s many windows, there are several areas of the building in which it is possible to see through the glass from the front face to the back. According to Miller, the birds likely thought that they could fly straight through the building. Instead, they crashed against the windows.

The highest rate of deaths occurred from early September to late October, during which many bird species were migrating for the winter. Seventy-two percent of all dead birds were recovered during this period. At one point, the rate of death was over one bird per day.

“There is a high correlation between the strikes and the migratory patterns of the birds,” Brassord said.

According to Miller, climate change has significantly affected bird migratory patterns. Spring migration, which is usually longer and more spread out, usually lasts from mid-March to mid-May.

However, birds have begun to migrate earlier in the season, which might account for the longer period of time in which bird strikes occured.

The bird deaths are also cause for concern amid the nationwide decrease in native birds.

Since 1970, the number of birds in the United States and Canada has dropped by 29 percent, according to a report titled “Decline of the North American avifauna” in the journal Science.

The report concludes that the “loss of bird abundance signals an urgent need to address threats to avert future avifaunal collapse and associated loss of ecosystem integrity, function and services.”

Even common birds such as robins and sparrows have sustained steep losses. Scientists theorize that ingesting pesticides and flying into windows caused many of the deaths.

Miller and Brassord will conduct an empirical test during the birds’ spring migration. Beginning March 1, they plan to close all the shades and limit lights in the science center during the evening and night hours. The facilities staff will continue to survey the area each day and collect data on bird strikes.

“Bird strikes are of concern to us all, and it’s important to thoroughly research mitigation options with our architects and other experts,” Brassord said.

Miller hopes that these measures will stop the bird deaths. If not, she has other ideas, including adding decals to the science center windows so that birds will realize that the windows are solid surfaces.

“We will see what the data reveals,” she said.