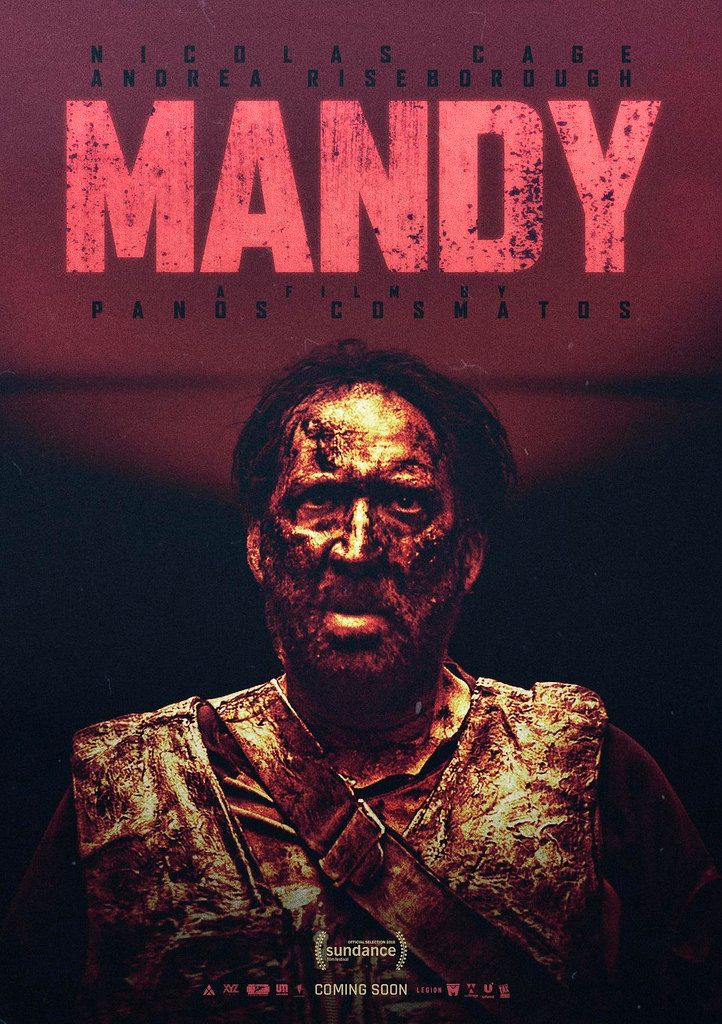

Demon in Red: Panos Cosmatos’ Film “Mandy” Fails to Please

Red Miller (Nicholas Cage) lives in the mountains with his artist-wife Mandy Bloom (Andrea Riseborough), hidden from the rest of society in deep and enduring love.

However, hints of the dangerous nature of their relationship surface: Red is a recovering alcoholic, and Mandy’s fantastical art sketches out the abstract contours of some undisclosed trauma.

On a regular day in the Shadow Mountains, they are visited by a dangerous cult that calls itself Children of the New Dawn — a gang of demonic bikers hungry for humans and hallucinogens led by one Jeremiah Sand (Linus William Roache).

This encounter soon leads Red to witness a tragedy that banishes all hope of recovery from his alcoholism, and soon he finds himself riding on the avenger’s path that is lined with the colors of hell.

There is little to recap in “Mandy,” director Panos Cosmatos’ alleged breakthrough and Cage’s alleged return to form. It certainly provides something: garish, neon and gruesome violence, reminiscent of the ‘80s and the aesthetic of excess attributed to that decade.

The plot, as a vessel for this throwback excess, is ironically simplistic: a man wants vengeance for being wronged, and he’ll brave hell and back for satisfaction. The lack of correspondence between form and substance appears to be the central conceit of the entire film, in which the threadbare plot draws attention to the almost undue overflow of apocalyptic imagery and thematic grandstanding.

Unfortunately, the appearance of mismatch between form and substance is all the film manages; every juncture of the movie strictly avoids any depth. In presenting one man’s life so comically and cosmically torn apart by a single event, the premise of the movie has the potential for a number of possibilities. Is the ensuing violence traceable to some selfishness that causes Red to view his life as more central to the universe than others? Can we call it selfishness if the cause of this violence was not one event, but a history of suppressed suffering activated by a moment?

Amidst this (lack of) choice between an instant’s offense and a resurfacing horror, where is the place for Red’s agency? Where is Mandy, who in her scarce presence throughout the movie, emphasizes its ill-fitting title? These are the questions Red’s warpath meticulously avoids.

Then, there is the issue of the warpath itself: how it is, how it looks, how it sounds. The film makes the curious choice in sound design to invert the background and the foreground. The wind whistling through the trees, the draining drone of electronica, the buzzing of satanic circles, the wailing of chainsaws: their collective wheeze swallows the dialogue whenever and wherever.

One might be tempted to find some clever excuse for such an intentional decision — the possibility of genuine connection and communication swallowed whole by the radiation of wrath and rancor.

But upon closer inspection, the muffled dialogue with a vaguely biblical sense of foreboding contains little of value. It is the film in microcosm: an empty aesthetic drowned out by boisterous noise.

The only aspect of filmmaking that flourishes is the aesthetic, but even this impresses for only the first two-thirds of the movie, at which point the elapsed time makes painfully clear the diminishing returns of the color red.

The color red is the primary mask for the film’s general emptiness, and the character of Red proves to be similarly disappointing. Cage stands out in virtue of everything else standing back. Riseborough’s Mandy shines her witchy visage from here and there, and the demonic bikers steal the scene when they are not obscured by the aforementioned flood of color.

Cage unleashes a character performance that can only be described as himself, or at least a knowing parody of the public’s idea of Nicholas Cage: unabashedly emotional, unfailingly intense and unwittingly hilarious. Cage has always been a canny actor, whose oft-cited vice for melodrama disguises the virtue of a tremendous emotional scope that is on display in films like “Adaptation” and “Left Behind.”

The character of Red Miller allows Cage to flaunt his underrated emotional range. When he kills demons from hell, he does it with glee that oversaturates everything in the room and briefly transforms the film into a comedy. When he sobs over the unending stretch of despair that is his life, the world seems to stand still in courtesy.

In a thinly-scripted film like “Mandy,” there is little buffer between actor and character. Unfortunately, the mindful depth of the former finds no transference in the latter, as the actor’s performance is unable to save the movie’s character.

Beneath the glee and the sobs, Red has no substance — no legible source of supposed trauma, no comprehensible psychological purpose to fulfill or fail. He, like his eponymous color, conquers the scene without any intent to govern. Two-thirds in, everything dies under red and Red.

One can only repeat at this point the pointlessness of this movie’s venture, whose only structuring insight is the basic, ironic mismatch between the what and the how, and the ignorance of the why. Unsurprisingly, the substance is trite, the method tired and the reason truant. Only the questions of when, where and who can be answered for this nothing-film: never, nowhere and for no one.

Comments ()