Portrait of an Amherst Poet: Eliot Cardinaux and The Bodily Press

Eliot Cardinaux is an Amherst-based poet, jazz pianist, publisher, and composer. Staff writer Luchik Belau-Lorberg ’28 spoke with him to learn more about his life and the art that informs it.

“Literary Amherst,” what the college likes to call its storied history of associations with prominent local poets and writers, was a prominent factor in my choice to attend the school. But where (and who) is Literary Amherst, really?

For many, the poet is, at best, a monumental statue, gazing vaguely across the Quad from a pedestal beside Memorial Hill; at worst, a disembodied voice droning in verse while you doze off in your 8:30 a.m. lecture. Despite the college’s historic associations with nationally-recognized writers like Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and Richard Wilbur, many current students stand unaware of the vibrant literary scene contemporary Amherst has to offer.

But a recent conversation with a real-life poet has confirmed my hopes that Amherst poets do exist. If you’ve frequented Amherst Books in recent months, one may have even handed you your change. Next time you’re there, look for poet, jazz pianist, and composer Eliot Cardinaux in his stylish tweed cap.

Aside from his job behind the counter at Amherst Books, Cardinaux is the founding editor of The Bodily Press, an independent press for poetry and record label for improvised music based in Amherst, MA. What began in 2017 as a way for Cardinaux — having just moved to Western Massachusetts — to self-publish his poetry booklets, or chapbooks, is today a home for poetry, music, and art collections by a diverse host of artists from around the world. Thanks to a small grant from the Amherst Cultural Council, Cardinaux hopes to expand the press’ portfolio of poets and artists with marginalized identities.

“I found it quite frustrating that the people who feel comfortable reaching out to someone like me are mostly white men, so I’m trying to work on diversifying things a little bit,” he shared.

Forthcoming from the press is a collection of chapbooks and recordings by a cohort of female and non-binary poets, including works by poets Shana Bulhan and Suzanne Mercury, musician and singer Deja Carr, and painter Tasha Robbins. Other works include poet Nathaniel Mackey’s new chapbook, “By Bent Light; THE ETCETERA VARIATIONS” by Denver Butson; and “A Smudge. Attenuated” by Iranian-born, Toronto-based, queer poet and translator Khashayar Mohammadi.

Brought together by The Bodily Press, this diverse collective of artists represents a meaningful artistic community for Cardinaux. “I like being around creative people,” he told me. “Everyone thinks of a poet, or an artist, or even a composer, sitting up in a room somewhere with their head in a score, or a typewriter, or a book, or a laptop, as it were. But so much of this artform, this poetry, is a very social thing.”

Shortly after we sat down at a lounge table inside the Boltwood Inn, Cardinaux handed me two of the press’ recent publications: a collection of his poems and an improvisational jazz CD recorded by Cardinaux and Gary Fieldman. Having developed a fierce passion for piano performance and jazz music in his teens, Cardinaux never paid much attention to poetry until his early 20s.

“Growing up, I kind of thought of poets as these dead old men from previous centuries,” he said. Around the age of 15, Cardinaux, who had a musical upbringing, “figured out [he] could improvise” and quickly committed to jazz as his “life calling.”

At 18 years old and fresh out of high school, Cardinaux moved from the suburbs of Dayton, Ohio, to attend the Manhattan School of Music and get into the New York jazz scene as an aspiring pianist. His first foray into poetry came in his third year of college on a nationwide road trip with a group of music school friends.

Cardinaux, at the time intensely focused on jazz music, tried his hand at lyric writing to “keep up” with his amateur songwriter friends. Dropping out of college at 21 to play jazz gigs in New York, Cardinaux continued experimenting with language, journaling in his spare time.

Things took a major turn in 2008. Feeling as though he had failed to “make the cut” as a musician, Cardinaux moved from New York to Western Massachusetts. It was then, in 2008, that Cardinaux was diagnosed with severe depression. While it is now something he experiences as a “low-level, dysthymic constant,” Cardinaux’s depression was, at the time, inhibiting his ability to function or participate in society. “I needed something to pull me out of it,” Cardinaux told me.

Still lacking any formal training in poetry, Cardinaux threw himself into the artform, reading everything he “could get his hands on.” He started with “The Wasteland,” by his namesake, T.S. Eliot, which led to the other modernists: Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, Marianne Moore, and later Elizabeth Bishop. Soon, the Atlantic gave way to the Continent, and Cardinaux — a native French speaker — moved on to the Russians and the French: Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, Paul Celan, and René Char.

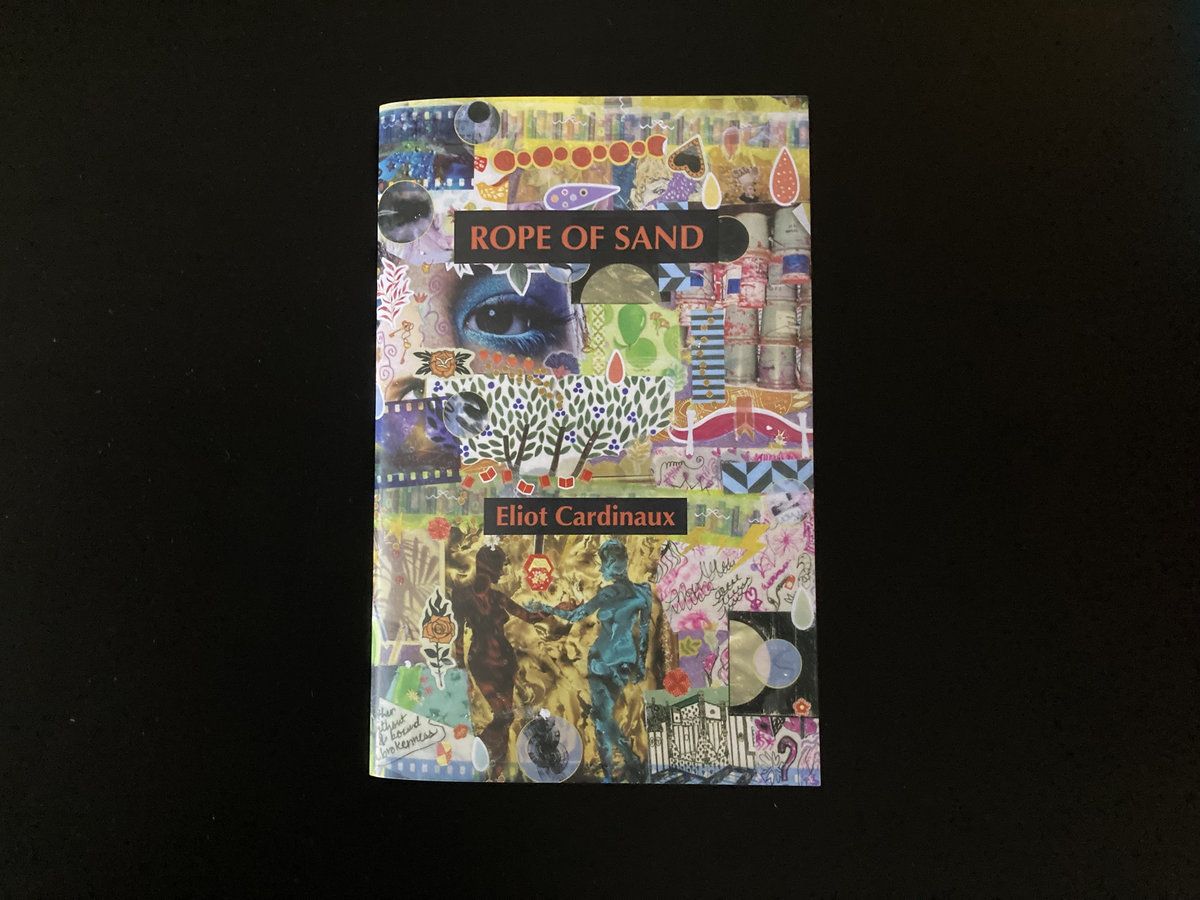

Cardinaux described the work of Osip Mandelstam, in particular, as a continual source of solace: “Here’s someone who’s been sentenced to death, and only by some bureaucratic miracle, has been sent into exile, has attempted suicide, and is now writing the most unearthly, beautiful verse that I’ve ever come across. And it made me feel like … I didn’t get to just give up on life, that suffering is not the art — it’s the overcoming of suffering.” Cardinaux’s 2024 chapbook, “Rope of Sand,” is a 24-poem sequence of consecutive “Miles,” which might be aptly described in its own words as “Obsessive forms, / preoccupied impressions // of collapse & fade. In failure / to abstract they differ in // particular and number, each / of a form in series.”

The book’s opening poem, “Mile Zero,” reads, “Sad, do you notice? / how these objects have // served their purpose.” I find Cardinaux’s placement of the interrogative at the end of “notice” rather than “purpose” particularly noteworthy. Interpreted as the line’s subject, “Sad,” (or “sadness”) becomes the question’s implied addressee, rather than a disjointed adjective. From the journey’s outset, the poet addresses us as his transient reader and as the “Sad” which has been a constant throughout his life.

Yet there is also an almost compulsive search for pairings in Cardinaux’s writing, a pattern of abstract nouns coupled by ampersands that he called a “a tick, a sort of obsession.” Sometimes, the pairings inhabit the same line: “collapse & fade.” Other times,a line break leaves an ampersand dangling like a grace note: “Tremor / & alm.” But, when an ampersand begins the stanza, we may be left with an incomplete pairing: “& what of the houses / gone to pieces?” In cases like this, Cardinaux asks us to leap across gaps to find the estranged pairing, or counterpunctual.

When asked about the prevalence of these pairings in “Rope of Sand,” Cardinaux told me about a formative experience that happened when he was 39. “This book was written not long after I tried to move to Denmark to be with a beloved, and this person decided, six weeks in, that she didn’t want to live with me after all and left me stranded in Copenhagen without my passport, with nothing. Her reason was that I was depressed.”

Describing a “heart laid open on a foreign beach & yours // in its bunker of amber,” in the poem “Mile Four,” Cardinaux evokes the film stills of Normandy. In its final stanzas, the poem blossoms into a diagram of dogfight aerodynamics — lift, thrust, and drag — a desperate struggle with an inexorable gravity.

“This poem was written grappling with the fact that because of my disability, I was sort of cut out of someone’s life,” he told me. “It was a bit of a wake-up call to understand that no matter how much I might try to assimilate into the sort of ‘normative world,’ I’m never really going to be the one with that privilege.” Still, the close contrasts of “self & losing;” “never // & retreat” represent the idea that “I didn’t really back down from who I was through all this, I was tied to this truth about myself, fettered to this element of my identity which to many people might seem undesirable.”

It is a poetics intensely concerned with esoteric personal experience, with the bounds of language, with the slippery slope from “perspicacity” to “precipitancy,” and with solitude. Like Paul Celan, one of Cardinaux’s most significant literary influences — a Holocaust survivor who battled depression until the end of his life — Cardinaux turns his sorrow into art.

Reminiscent of Celan’s elliptical neologisms, “Mile Nine’s” “Pink tendons of wordpair, knotted over each other,” have an epistolary ring to them, demanding the reader’s careful imagination, empathy, and consideration. “My ability to feel things deeply, to empathize with others who might be struggling — it gives me the charge of writing poetry … I thought, if there’s something to be said for shedding light on my own experience, it’s that someone else might stumble upon that experience,” said Cardinaux.

Throughout our conversation, Cardinaux was transparent about his artistic influences, collaborators, and partners, a long list of individuals spanning his entire life and generations prior. “There’s individuality in art, sure, but individualism is a trickier, slipperier slope, especially in a world with increasing courage to discard those who need special accommodations.” The encyclopedic arsenal of quotes Cardinaux readily deployed throughout our conversation — snippets of verse and mottos by his favorite writers and jazz musicians — struck me as a testament to the emotional solace that art can provide across space and time.

“I think poetry was always somewhat associated with therapy to me because therapy is where I first learned to articulate my emotions,” said Cardinaux. “So that’s what I’m trying to do — I’m trying to facilitate the movement of emotion, even if it’s not easy. Because I think a lot of us get stuck in our daily ruts and our daily routines, and poetry intrudes on that a little.”

With a potential move to Denmark to pursue graduate studies at the Rhythmic Music Conservatory in Copenhagen imminent, Cardinaux reflected on the future of The Bodily Press, which he called a “fraught question.”

“I’d like to continue to do this without driving myself into the ground financially,” he told me. Facing funding shortages in post-pandemic America, many beloved independent presses and bookstores — vital habitats for poets and other endangered species — have been forced to shut down. The Bodily Press itself has stayed in business due, in part, to the success of a crowdfunding campaign hosted in December, 2024. While the community’s support for The Bodily Press reflects an ongoing commitment to local artists, maintaining an independent press — even in the heart of the Pioneer Valley — remains difficult.

“It’s not exactly easy to convince some arts council panel that poetry is going to change the world. I don’t think poetry functions necessarily to end world oppression, but it does, in John Berger’s words, ‘incite a caring toward a particular thing that has been named,’” said Cardinaux. “And in doing so, you could say it raises awareness, but it also touches a place that no other language can touch. Music is also very beautiful in that way — and it does it without words somehow.”

For Eliot Cardinaux, founder of the Bodily Press, art is a vital antidote to grief and apathy. At its core, Cardinaux’s multifaceted work is about the joys and sorrows of human connection and care. If you see him at Amherst Books, ask for an autograph.

Comments ()