Seeing Double: F*ck You, Foucault

It’s hard for me to be an idealist at Amherst College. Principles like justice and freedom, which once seemed unambiguously good, seem unattainable or even undesirable after three years here. My moral compass feels like it has lost its magnetic pole. One might feel tempted to blame the detachment caused by the pandemic, but I think the reason for the apathy so many of us feel goes beyond Covid. Much of it comes from things we learn in our classrooms.

A specter is haunting Amherst — a specter known as postmodernism. In essence, postmodernism argues that all supposedly objective truths — morality, instinct, and even many sciences — are constructs built on social and historical processes. Postmodernism challenges what people think to be universal truths as instead relative to the historical moment in which those truths live. I am not here to argue that postmodernism is wrong or should no longer be taught, but rather that when misinterpreted in undergraduate settings, postmodernism has the potential to breed apathy and nihilism. It’s not hard to see why. If our ethics, beliefs, and values are all entirely contingent on historical conditions, how can any action be objectively good? If postmodernism is correct, how should we live our lives?

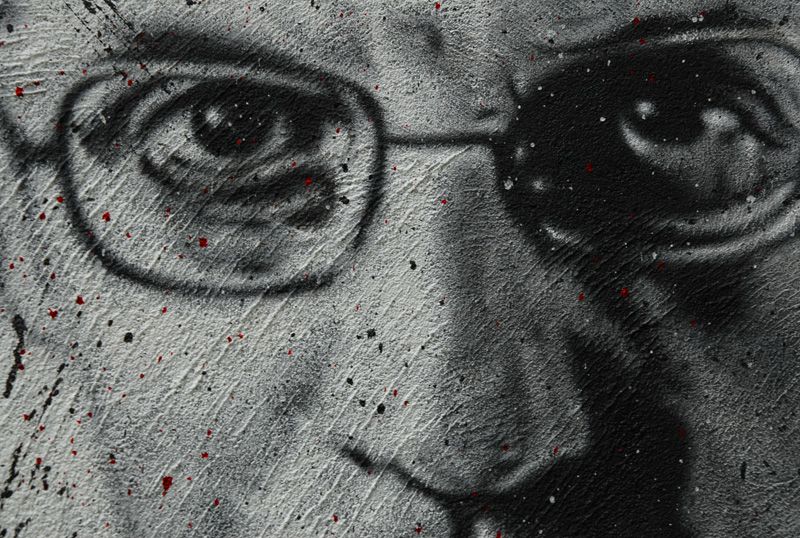

One classic example of the way postmodern philosophy might inspire nihilism is the classic 1971 debate between postmodernist legend Michel Foucault and famous anarcho-syndicalist Noam Chomsky. In the debate, the two thinkers discussed what a perfect human society might look like. Or rather, Chomsky did, describing in detail his goals of justice and “the realization of the essence of human beings.” Foucault, on the other hand, proposed no ideal society, but with Gallic aplomb denied the existence of any true concept of justice or human essence.

After the debate, Chomsky described his shock at the cynicism of Foucault’s argument: “He struck me as completely amoral, I’d never met anyone who was so totally amoral.” The assertion was probably unfair. Many philosophers have argued that postmodernism in no way entails amorality or nihilism. Indeed, I am not a philosopher (just like my sophist of a co-columnist) so I can’t speak to the intricacies of Foucault’s writings.

What I believe, however, is that just like Chomsky heard Foucault and imagined him existing in a world without morality, Amherst students may have difficulty squaring Foucault with any kind of moral framework. If it can happen to an academic with the pedigree of Chomsky, it can happen to an undergraduate, and speaking from personal experience, it has certainly happened to me. Worse yet, Foucault is everywhere in undergraduate humanities. He is far and away the most cited 20th century scholar in the humanities, to the point where I rarely have a class that doesn’t mention him at some point.

That’s worrying because a serious dissonance exists between postmodernism’s important place in academia and Amherst’s idealistic mission. Amherst as an institution marinates its students in the very universalist idealism that postmodernists critique. Even our motto, Terras Irradient, speaks of Amherst as a moral force for good not only in our own community, but throughout the world. That moralistic vision extends to today, when Amherst gives its speech competitions broad (and to a postmodernist, irresponsibly global) themes like Justice, Freedom and Truth. Yet at the same time, the postmodernist bent of its classes suggests to students that it is impossible to agree on the meaning of those very same ideals.

The problem is not postmodernism itself. Rather, it is the deconstructionist way in which people often interpret it. Instead of just tearing down all ideas of morality or society, we should emphasize the ‘what now?’ Many brilliant postmodernists, such as Jacques Derrida, have attempted to lay out a kind of postmodernist ethics, that explains how we can value principles while acknowledging that they are social constructs. We must ask the central question: how can we live good lives within a postmodernist framework?

Amherst College should produce idealists. Grounded and well-informed ones, to be sure, but idealists nonetheless. Yet the way we teach postmodernism has made idealism increasingly difficult. If even liberal arts students cease to be idealists, who will be?