Student Cinema Stuns at Premiere Showing

Piper Mohring ’25 and Caden Stockwell ’25 showed their short film this past Saturday, Sept. 17, to a full house in Keefe Theater. Jacob Young ’25 reviews the film, which was narrated in French by Community Service Officer Merouane Daffar and filmed in Paris.

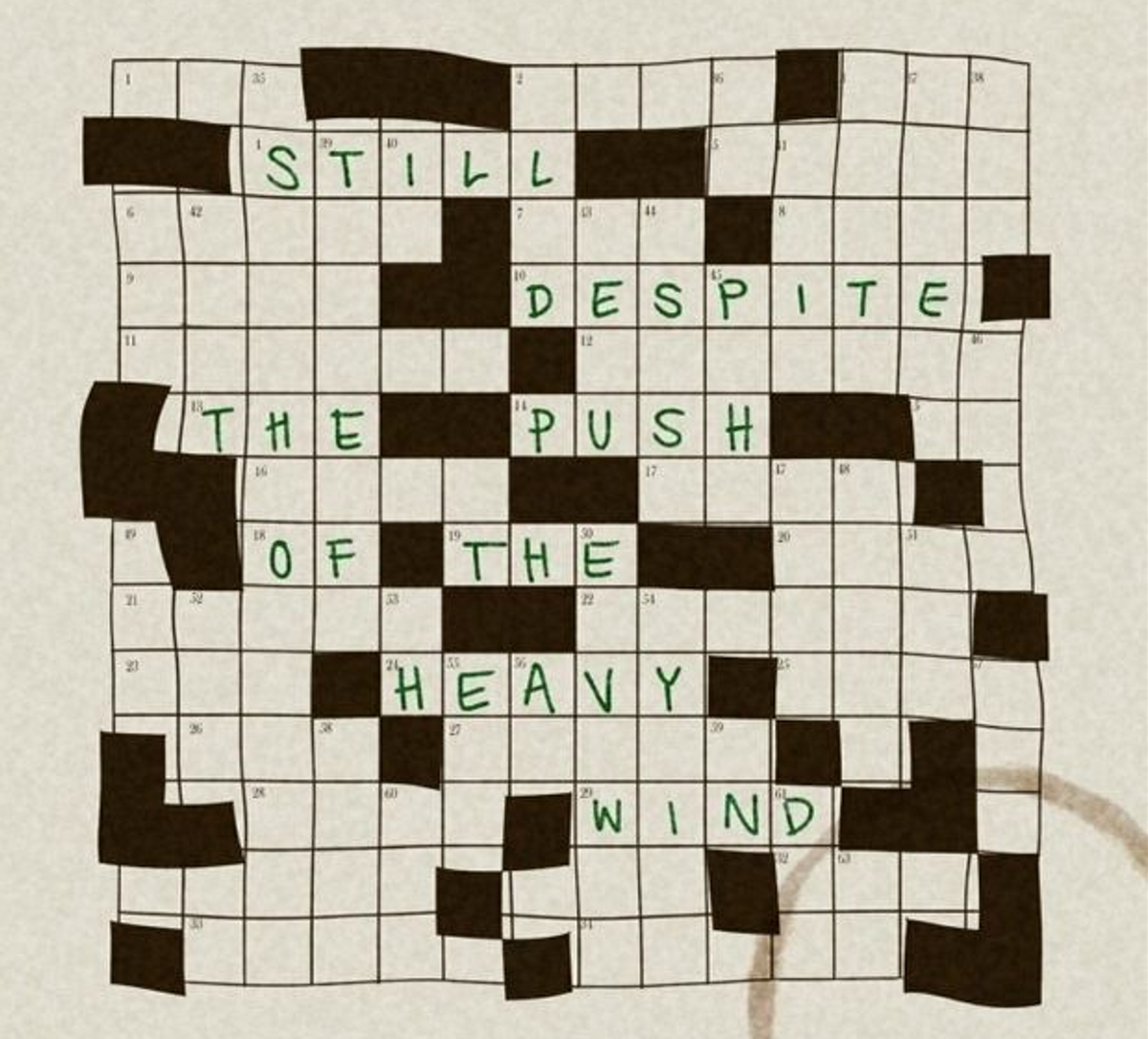

Excitement ran high in the Keefe Campus Center Theater on Saturday, Sept. 17, where a sizable portion of the Amherst College community excitedly gathered for the premiere of “still (despite the push of the heavy wind).”

The film, just under half an hour long, was written, shot, and directed by Amherst students Piper Mohring ’25 and Caden Stockwell ’25. The principal photography took place this summer in France while the directors were taking a Hampshire College course in Paris. The course was in Super-8 filmmaking, but this film was shot on a digital camera that the two lugged with them on each of their outings and during the week after the course ended. The film is narrated in French by Community Service Officer Merouane Daffar, who ran the college’s quarantine program at the Rodeway Inn last year.

Before the movie began, I asked members of the audience what they were expecting. “It’s the greatest film of all time,” said Hunter Kloss ’25. “That’s what we’ve all been told.” Gracie Rowland ’25 thought that it would have a lot of symbolism and landscape shots.

The audience was also excited as the HDMI: No Signal box, which had been blinking around the movie screen for several minutes, appeared to be on a trajectory toward the exact corner of the frame. At the last second, however, it bounced off a higher-than-expected floor. This was the only disappointment of the night.

In “still (despite the push of the heavy wind),” the audience never sees the narrator/subject (Daffar), but we come to know him well because of the presence of his voice throughout the film. He monologues about the “monotonous movements that constitute all of existence” and meditates on his own memories and malaise. In the beginning, much of the film’s footage consists of simple handheld shots of street life in Paris, edited to match the images and ideas referenced in the monologue. Since we never see the speaker, it feels as though we are looking through his eyes; but due to the handheld, cinema verité style, we are also aware of the fact that we are looking through the lens of a camera at a replay of reality. This produces a feeling of intimacy between the viewer, the subject, and the filmmakers: We are all searching his memories for the source of his apathy.

Indeed, we find a multitude of potential sources in the recurring symbolic images of the film. When the subject-narrator says, “Some of us may be remembered long after we die. The overwhelming majority of us will not,” Mohring and Stockwell juxtapose a shot of a grave smothered in lipstick kisses at the Père Lachaise cemetery with one of a cat lounging on another gravestone next to a monument marked, Concession à Perpétuité (“Concession to Eternity”). The cat, presumably, is not aware of the meaning of its gesture. Ignorant and visibly content in the light of the day, it mocks the human desire to be eternally monumentalized.

Most of the film’s symbolic power, though, is not in the content and composition of its images, but in the manipulation of the medium itself. Some say that setting formal constraints on a project encourages artists to tell stories more inventively — that limitation breeds creativity. Mohring and Stockwell either did not hear them or decided to prove them wrong. Their film sets no bounds on cinematic expression, but rather manipulates formal aspects of film, like color, time, and frame, to tell the story of their subject’s alienation from and disillusionment with every aspect of life.

For the narrator, meaning does not come from the miracle of birth, life under the state, or the gravitas of death. When he relates the story of his own birth, he does not situate it in his personal or familial history, but rather in United States History with a capital ‘H’. He rattles off a list of dates: the birth of Osama bin Laden, the passage of a Wisconsin budget bill designed to suppress unions, the assassination of MLK. To represent just how little meaning he ascribes to these morally charged events, Mohring and Stockwell play clips of old newsreels at higher and higher speeds, creating a montage of military-industrial and governmental operations. The footage is in black and white, the frame size is smaller than the rest of the film, and the speed of the video and audio gradually speeds up until the newscaster’s voice is unintelligible, the motions are comical, and the subject informs us that “approximately 385,000 babies were born that day.”

All the while, Daffar’s tone is forlorn and faraway. Everything is equally meaningless to him. This message is explored further when Mohring and Stockwell split the screen into four smaller screens, each depicting a different image mentioned in the monologue or a different moment in the subject’s life. Unable to distinguish if any of it has mattered, each screen disappears until only a broken egg remains on screen, its yolk spilling into the gutter water.

In the middle of the film, when the subject describes walking around the city as a sort of living nightmare, streets and rivers ripple with the sped-up passage of time, and a carousel spins faster and faster — until the montage crescendos and he finds stillness in the Luxembourg Gardens. That stillness does not dispel his torment, though. He experiences the stillness of life as a rapid, violent succession of moments, so repetitive and meaningless that they begin to occur simultaneously.

The third portion of the film features increasingly intense superimpositions of images from all realms of his mind. As the narrator loses his grip on reality, the formal manipulation of the images intensifies: The colors are filtered more heavily, the human figures are fried or angrily scribbled out, time itself becomes turbulent and even reverses. After his mother dies, the narrator escapes from this whirlwind-nightmare only when it deposits him in a forest, “still despite the heavy wind.” He decides to buy a ticket to a part of France where he’s never been, thinking “maybe the best way to honor the past is by forgetting it.”

In the last scene of the film, the subject runs along a narrow path of vineyard, into the wind, and finally bursts out to look over an open vista. As the dreamy piano music decrescendos, it is up for interpretation as to whether or not he has found peace. I believe that the last line of the film is a declaration that he has accepted the mundanity and unhappiness intrinsic to being and grasps the essential commandment of life: Go forward into it, anyway.

All in all, “still (despite the push of the heavy wind)” is a compelling and creative film that will be enjoyed by the incurably adrift, the eternally doomed, and fans of Jonas Mekas and “How To with John Wilson.” It was made by people who love to mess with video editing. The end result is not a mess, however. If it was an HDMI: No Signal box, it would, without a doubt, hit the corner of the screen.

The film can be found online on Mohring’s YouTube page.

Comments ()