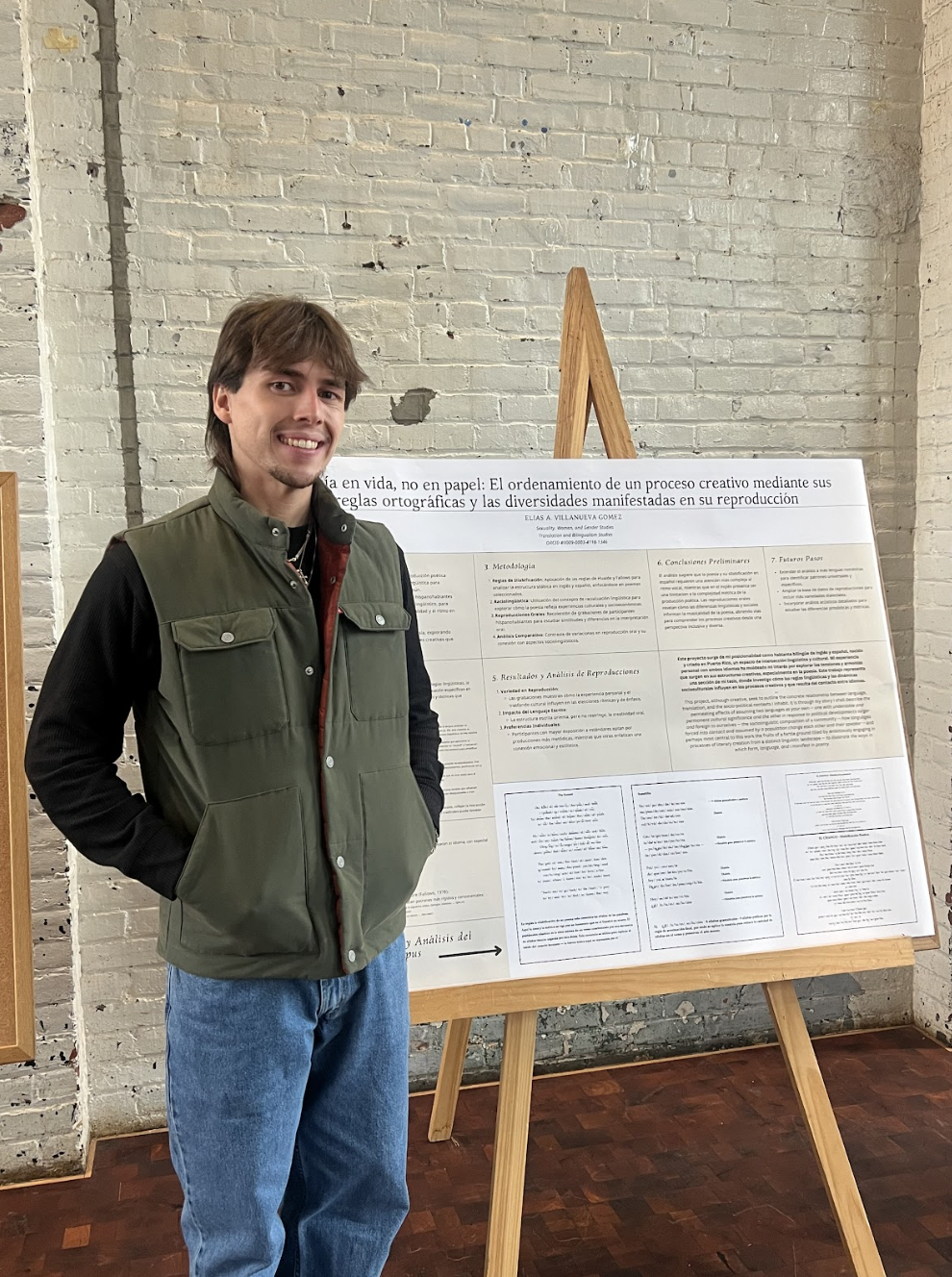

Thoughts on Theses: Elias Villanueva Gomez

Elias Villanueva Gomez ’25 is a senior double majoring in Sexuality, Women’s, and Gender Studies and an interdisciplinary major, which focuses on translation and bilingualism studies. His thesis explores philosophies of translation, sociolinguistics, and translanguaging.

Q: Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and your journey to Amherst?

A: [Growing up,] I didn’t know about Amherst. The liberal arts colleges were just a figment [of] my imagination. And then one day, my aunt was just like, “You should apply to Amherst, it’s a really good school.” And also, “ if you get in, it’s, like, super need-blind so you could probably get a full ride.” And I wasn’t really gonna try, but she kept pushing. And I was like, “Okay, I’ll do it.”

Long story short, I applied to Amherst. I got the acceptance … and yeah, I ended up here. [Being from San Juan, Puerto Rico,] it was the first time I had ever come to New England, or this part of the States in general … It was really hard at first. In my freshman year, there were more shocks and differences than I expected. I came here with the idea that language won’t be an issue, and because I know American culture, this wasn’t going to be anything too crazy. It was completely crazy. Bonkers. [By] mid-November, I wanted to leave.

Q: Why did you want to leave?

A: I had really small interactions that kept adding up … It would be small things like, “Oh, I noticed an accent. Where are you from?” And then the minute you have to explain yourself: “Oh, I’m from Puerto Rico, I live in San Juan,”… It just shifted my relationship to the place where everything felt like, “Oh, if I can’t place you somewhere and just call you something, then I have no way to interact with you.” So that, in and of itself, was very jarring.

I was ready to leave. I applied to transfer back home … It wasn’t until my sophomore year that I thought, “Wait, this is the last day: I have to either enroll back home or stay at Amherst.” And I stayed at Amherst … And it took a minute, but slowly, I’ve come to love this place. Part of being a senior is that you look back on everything so fondly … I think in typical Amherst student fashion, I wanted an Ivy, I wanted to be the best. I wanted to pursue some type of recognition or validation for all my hard work in high school. And I didn't know it at the time, but ultimately, that is what I accomplished and I feel very positive about what's to come.

Q: How would you describe your thesis in a nutshell?

A: A statement that I really enjoy about the thesis is, “Can we use language, or, in this case, the term hybridity, to capture linguistic realities and also socio-historical, cultural contexts.’ I think, through the language of hybridity, we can offer a multi-spatial framework to understand language as both scientific and a product of sociological interactions. Yeah, that’s my spiel.

Q: You are a Sexuality, Women’s and Gender Studies (SWAGS) and interdisciplinary studies major, correct? And your thesis is in your interdisciplinary major?

A: In my interdisciplinary studies proposal, it says ‘translation and bilingualism studies: the transdisciplinary study of language hybridization and bilingualism.’ When I wrote it, I was very focused on the actual mechanical act of translation … And as I’ve progressed [within] the major, where I am now — especially with my thesis — is the field of sociolinguistics. That is, not only the mechanical linguistics of language, where we talk about elision or the isonomic meter of the syllable, but the “socio” part, where I bring in this SWAGS discipline where we analyze context. Like, where exactly are we generating knowledge from? Is it experience or are we theorizing in a void? Are we in conversation with scholars or with a community?

And a vein of thought that I've exploited is this idea that I cannot talk to you about the science of linguistics without talking to you about what groups of people hybridize[d] and fuse[d] to create what we know now. If I want to talk to you about Puerto Rican Spanish, I have to mention the Spanish of the Canary Islands. I have to talk to you about the Spanish of Andalusia. I have to talk to you about the Yoruba languages of the slaves that were brought to Puerto Rico. I have to talk to you about the Arawak that the Taino spoke, because all of these little puzzle pieces ultimately gave birth to my language. And even [in] contexts that are so similar, like the Dominican Republic, [Spanish] manifest[s] so differently. It's not only racial and historical context, but also geographic context — what about the land has informed the language.

Q: How does this idea inform your thesis?

A: All these theories and linguistic ideas describe something, but never physically. In my thesis, I want to propose something that is both a description but also an active mechanical process … because in speaking of hybridity — the term I coin/posit in my thesis — you talk about the description of language contact, but you also talk about larger, more active processes, which are slightly atemporal and always umbrella term-y. That’s what I’m working on in my thesis.

I have [my thesis] divided into almost three sections, drawing from SWAGS, indigenous studies, and interdisciplinary studies … [One is] the experiences that inform content — where I learn from; [one is] the theory, what I posit, which is a process and a mechanical description but is also critical; and [one is] an application. Because ultimately, I can go on with my theoretical mumbo jumbo, but if I can’t apply my theory and show you how it’s working, then it’s lost in the void, and I get lost in the sauce, as I like to say. So the first three chapters establish that experiential basis, the description, and then also the theoretical maneuverings. And the remaining three chapters are case studies in how this process of hybridity… manifest[s] in poetry, specifically in poetic form … I talk about the nuances between having a sonnet in English and a sonnet in Spanish, which are fundamentally different.

Q: How are you distinguishing between the English and Spanish forms?

A: I’m zeroing in on the fact that the iamb is possible in English, but it’s impossible in Spanish. If we boil it down in linguistic terms, it’s because English is time-stressed, and Spanish is syllable-stressed. English has inconsistent phonetics — only in the act of speaking do you know where the inflection goes. And then Spanish is so consistent grammatically that the written language informs how you speak. Like, we wouldn’t know how to speak English if it weren’t for the fact that [the spoken language] survived. So of course I talk about those minute, scientific differences. And then, in the cultural tradition of poetry, English has a less rigid but more rhythmic and liberatory practice of poetry while in Spanish, the form is so rigid and so metric and so mathematical, that it could sound dissonant and almost cacophonous — but if the numbers check out, the scholars are eating that up.

Once I introduce form, I look at the sonnets in parallel. I’m drawing from a lot of critical studies and this idea of research through practice … So I currently have about 15 sonnets, and they’re all written by me. I think it’s seven in English and then eight in Spanish, or vice versa.

I look at the Spenserian Sonnet and “el sonetillo,” coined by Federico Garcia Lorca. And then you have the traditional Italian romantic sonnet … I also look at Garcilaso de la Vega, who draws from Petrarch and creates the sonnet in Spanish as we know it. I have hybridized forms of sonnets where I look at the differences between English and Spanish. I also zero in on the similarities and try to create rhyme between languages and to fuse form.

For example, English has 12 vowel sounds. Spanish has five. But it so happens that those that exist in Spanish are also present in English. So through this exercise, I’ve managed to preserve traditional Spanish poetic meter and rhyme [while writing in English.] Within this theoretical framework of language fusion and hybridity, there is actually so much freedom. English can adopt so many things, from syntax to inflection, from Spanish, and vice versa.

And then to counterbalance this, I’m looking at the concrete philosophies of translation — what it means to translate content versus translate form in the Spanish poetic tradition. That one is slightly more challenging to draw a narrative thread through, because it’s not one singular form, but rather four out of the five classic Spanish forms.

The idea of translation as a bilingual and hybrid mechanism is present throughout what I have tried to construct in sociolinguistic terms. And the cherry on top, to conclude but also throw everything away in a way that’s very SWAGS major-esque … I end my thesis on an analysis of translanguaging to speak on how bilingualism and language contact is heavily informed by context and by geography, history, [and] culture. Through translanguaging, I look at free verse as a way to encompass the liberatory practice of analyzing everything through both linguistic and sociological terms. A big factor in the sociology of it all is raciolinguistics, which is this idea that the violent encounters of colonialism are innate factors in understanding why people sound the way they do.

Q: What have you learned from this thesis that has surprised you?

A: I’ve gained a profound appreciation for language and the orality of it all. I’ve learned that every context is so unique and irreplicable, that we really have to zero in on the importance of preservation. We also need to make sure these small differences are accounted for and celebrated. Do you ever think about all the humans that have ever lived that no one knows existed? You may not know them, but you’re thinking of them. The way I’m speaking is not me, but rather, hundreds and millions of people that have come into contact, and through this random, aleatory combination resulted in you, specifically, because you don’t sound like me and I don’t sound like you. We may have similarities, but everyone has their own dialect … My first chapter is an autoethnography. It’s how my life also reflects society. We live in a society and there's so much theory that goes into that, but it’s also my story … I think we are in the golden age of experiential learning, where finally we can say … that we learn from our daily lives.

Comments ()