“Tuca and Bertie”: A Comedic Look at Modern Adult Life

Adult animation has had a resurgence on Netflix, including cult hits such as “Bojack Horseman” and “Tuca and Bertie.” Joe Sweeney ’25 reviews the latter, which follows two birds as they deal with adult problems, such as relationship issues.

Tell me if this has ever happened to you:

You’ve had a job for a while, but yesterday, you finally put your foot down. You’ve had enough of being exactly what people need you to be, at every moment of every day. Your work matters to you; your ideas about your work matter to you too. There comes a time when speaking up is the only remedy for the aching pain you’ve inflicted upon yourself through your silence. So, just this once: You speak up.

And everybody loves it! They think your idea is fantastic! So fantastic, in fact, that you’ve been put in charge of making it a reality! After that sensational meeting, your boss pulls you aside: “Say, [your name here], why don’t you speak up more often?” And you have no idea!

So now it’s off to the races: budgetary committees, investor meetings, board examinations. You’ve never been in a position like this, and right away you see that it is grueling. But this is what you wanted, right? This grind toward a goal that is truly important? Right!

Except the budgetary committee made a few cuts here and there … The investors are withholding their loan until until a few key things get done … The board said this part isn’t very “on-brand” ... It’s beginning to seem like the thing you’re doing all this work for is really gonna suck. But something is better than nothing, right? Right … or maybe you just have to believe that so you don’t have a nervous breakdown.

Alright, let’s really set the stage now. You’re doing the most important work of your life, but it’s important not for the reasons you wanted it to be, but because it’s your first experience watching your innermost dreams die, in real time, in-and-by your own hands — like a malnourished butterfly, too feeble to recover. You feel bad about telling your partner about all this because they’re having a tough time at work too, so you just don’t. Instead, you strike up a rapport with your “stall buddy,” because your daily pilgrimage to the bathroom is the only free moment you ever get. When you hang out with your stall buddy after work one night, you decide it’d be good to introduce them to your partner, as proof that your life is semi-normal and semi-stable. In the course of conversation, however, some choice opinions of theirs reveal they are, uh, a poopy person (everyone seems nicer on the other side of the stall).

Now your partner is kind of pissed at you. You don’t even have your stall buddy anymore — and you just can’t take it. So you go into work, burst into a megalomaniacal rant, and defecate on the floor. Because you just had to do it — but only because what you really want to do is go home and curl into a ball and never dream or care about anything ever again.

Has that ever happened to you? Something like it, maybe?

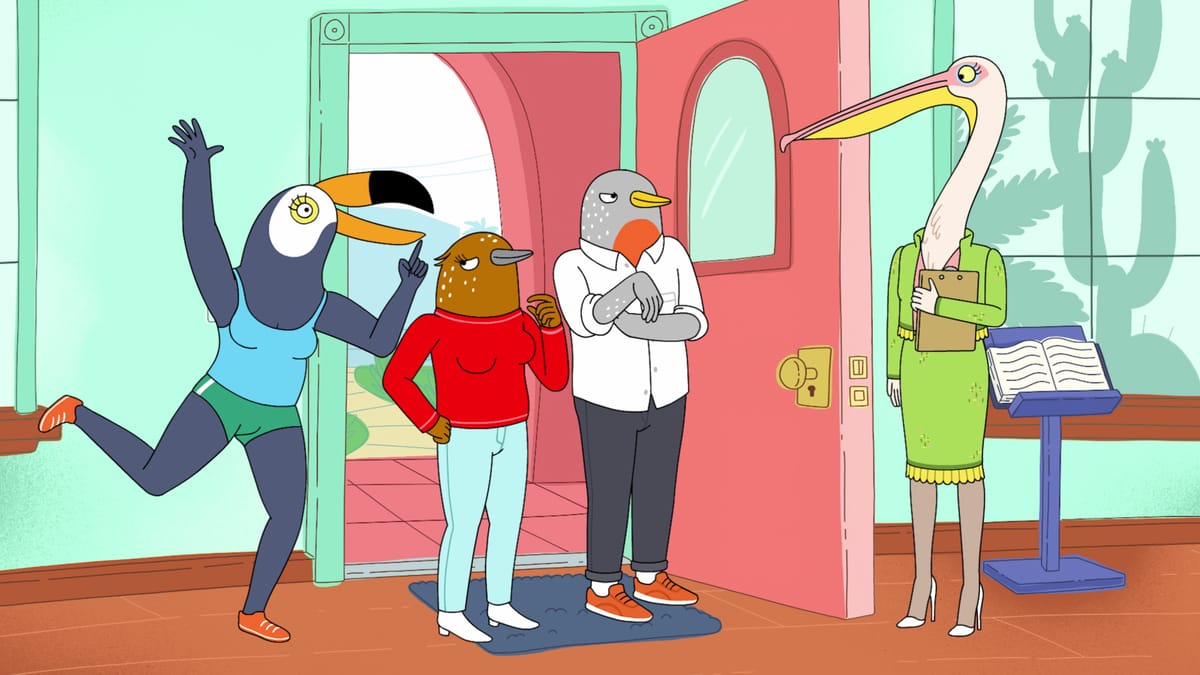

For me, “something like it, maybe” is the essence of “Tuca And Bertie.” The arc I just described concerns Bertie’s boyfriend and perpetual side character Speckle (voiced by Steven Yeun). The show is an animated comedy for adults which centers around best friends Tuca (Tiffany Haddish) and Bertie (Ali Wong) trying to figure out their 30s in the big city of Birdtown. It’s called Birdtown because most of the characters in the show are, in fact, birds (although some are animate plants).

The show was created by Lisa Hanawalt, who worked as a production designer and producer for “Bojack Horseman,” easily the most critically acclaimed adult animated series of the last decade. “Tuca And Bertie” has been met with similar praise; unlike “Bojack,” however, it’s had a turbulent production history. Released by Netflix in May 2019, the show was canceled in July of the same year, only to be picked up by Adult Swim in May 2020. A second season premiered in 2021, followed by a third in July 2022, which wrapped up on Aug. 29.

I’m going to use comparisons between “Bojack” and “Tuca And Bertie” to elaborate on the latter's central qualities. That being said, as much as I love “Bojack” myself, I don’t want to belabor the similarity between the two shows, not only because “Tuca And Bertie” is excellent in and of itself, but because the two really are very different.

The foremost of these differences between the shows is tonal. “Bojack Horseman” is commonly referred to as “the sad horse show”: it’s a dramedy about an aging, alcoholic, drug-addicted, traumatized ’90s-sitcom star who ruins the lives of everyone around him and is also a horse. Why is he a horse? I don’t know — why is anything, anything? This melodramatic absurdism, which toes a fine line between irony and sincerity, is both the humor and the pathos of the show.

On the whole, “Tuca And Bertie” is much lighter. Again, it’s a show about best friends, and so I feel that it must be, to an extent, a show relying on tropes. Bertie, a song thrush, is awkward, career-oriented, sweet, anxious, and generally a goofball in spite of herself. Tuca is a toucan, which is to say she is is unapologetically herself: brash, funny, and often sexually-driven. Many episodes are built around the ways their different personalities bounce off each other.

Admittedly, though, that bouncing is more explicit in seasons one and two. By the third season, both the content and the form of their friendship has been well-established. The third season experiments with both by sending each character into the world on their own and then seeing how they reconvene (form); how they reinvest in their relationship (content). In any case, there’s enough insanity in the world without having to worry about other people. In one episode, Bertie is devoured by a snake, and, continuing to go about her day-to-day life while protruding from its stomach, she makes broad gains at work because people mistake her new intimidating appearance for the confidence she never had. Tuca gets a job as a river tour guide and has to train her duckboats (which are alive) by giving them an outlet for their aggression (she uses Bertie’s boyfriend Speckle as that outlet, which results in him getting brutally stomped on — twice).

“Tuca And Bertie” takes “Bojack’s” absurdity a step further by letting a free range of possibilities develop indiscriminately in its world. The casual excitement of these unbelievable developments feels very true to the spirit of weary eagerness of many young adults: “Oh God, another new thing? Is this supposed to have some sort of deeper metaphorical significance? All I know is that it’s stupid and annoying … Well, OK. I guess it’s a little fun too.”

One of the strongest points of “Bojack” that has translated to “Tuca And Bertie” is a robust sense of visual comedy. There are so many scenes in “Bojack” that take advantage of its weird animal-human world to make a clever visual pun or gag. The world of “Tuca And Bertie” is alive with the same imagination. Giant snakes serve as trains for the city (there are regular snakes and train snakes). Crossing guards hold up traffic for a mama duck crossing with her children (there are people-ducks and regular ducks).

“Tuca And Bertie” has unerring confidence in its strangeness, making it a wonder for all to see. There’s a visual gag where Bertie shrinks every time her mom makes her feel insecure. In a later episode, Tuca needs a surgery, and her surgeon — a mole who climbs inside his patients to operate — gets lost in a hallucinatory dreamscape within Tuca’s uterus. To save Tuca, Bertie calls her mom so that she can insult her — thus shrinking her down to a size where she can climb into Tuca’s uterus and perform the surgery herself. Yes, relationships are strange, and sometimes that sucks. But because of that very strangeness, they can help us in ways that we could never expect; ways that don’t make any sense. Ways that become possible because they don’t make any sense. And that is wonderful, says “Tuca and Bertie.”

If I didn’t just make it clear, “Tuca And Bertie,” like many adult animated comedies, revels in vulgarity. But unlike some of those other comedies — e.g., “Family Guy,” “American Dad” — “Tuca And Bertie” rarely indulges in vulgarity simply to be provocative. In contrast, the crudeness in “Tuca and Bertie” is a manifestation of the overflowing good feeling which is at the core of the show. In one episode, Tuca is trying to rebound from a failed relationship. She becomes implicated in a prophecy: A chosen one will have sex with the entirety of a professional sports team (though the sport is professional raking, and all the athletes are middle-aged dads). She succeeds, thus freeing all who tried and failed before her of their eternal curse, which binds them to live in said professional sports team’s stadium. If that sounds insane, I would admit to you that it is one of the season's weaker subplots. Yet its simple fearlessness — embracing a moment that other shows would portray frivolously — allows the show to transcend itself even in this rare moment of mediocrity. It is the mark of a show that is deeply comfortable with itself; and what could be more worth watching, more worth waiting for to see what it has to reveal?

“Tuca And Bertie” is about fierce love: for the world and for your friends. Yet the show deeply tunes itself into the ways our inner love is unfit for the outer world. And so, in its darker moments — the grief of a failed romance, or of failed intimacy with one’s parents — the show reveals a world in which the love we receive from others is unsatisfactory and disappointing. I’ll always remember one scene in the first season where Bertie, on the twilight side of love, looks up at her apartment window from outside. The art style has changed with the night: All the buildings are only outlines of themselves. The only solid thing was the light from that window, and as I looked up with Bertie, I thought of the warmth of her home and its comfort. But I also wondered: Is this all there is?

In my own life, there are few things more valuable than looking for answers to questions like that.

After his work fiasco, Speckle comes home in season three to the same apartment — feeling distraught, and perhaps unforgivable. As viewers, it’s easy enough for us to see all he’s been through and expect an answer for it all: What are we supposed to do when love goes so wrong?

Instead, Bertie pulls out an imaginary “worry-vacuum” — think of one of those vacuums that is used for furniture, one that has a long tube that you hold the end of — and holds Speckle in her lap, softly working the vacuum over him, all while adjusting the “vroom” sound she makes with her mouth to his preference. No answers; only more love, in whatever shape it takes.

“Something like it, maybe” — if we’re lucky. The good thing is that we usually are lucky. More so than we might think, anyways.

Comments ()