“Twin Peaks: The Return” Revives Lingering Questions of its Past

“Twin Peaks: The Return” tells the story of FBI agent Dale Cooper, who in the original series was assigned to solve the murder case of Laura Palmer, the high school homecoming queen in the town of Twin Peaks, Wash. Over the course of the original two-season run on ABC, Agent Cooper unraveled the mystery of the killer only to find himself entangled in a greater, older, cosmic mystery involving demons, hell and heaven; a mystery whose indelible images constantly refused to cleanly classify themselves as reality or metaphor. By the end of the original run, Cooper found himself trapped in one of these literal/allegorical hells. Now, 25 years later, he is released under mysterious conditions and circumstances to a changed world, armed only with the knowledge that his doppelganger is wreaking secret havoc. Ever the upstanding agent of the law, Cooper navigates his return to the world, and his inevitable return to the deceptively comely town where all this chaos began.

“The Return” and its forerunner are, by design, impossible shows to summarize, but perhaps the best place to begin is with the latter and that subtitle. It is difficult to speak of “Twin Peaks: The Return” without talking about the idea of the ‘return,’ and it is doubly difficult to speak of returns without speaking of origins. The influence the original two seasons of “Twin Peaks” have exerted on American television is as overwhelming as it is surprising. It was an eclectic show, possessing little to none of the grit and tonal control of contemporary prestige television, preferring to hit every viable beat within every viable genre. Writer Mark Frost brought the tunes of his “Hill Street Blues”, headquartering the drama once more in a single police station beleaguered by a many-faced mystery. Frost’s police procedural was but a chassis for the eccentricity of co-writer and occasional director David Lynch.

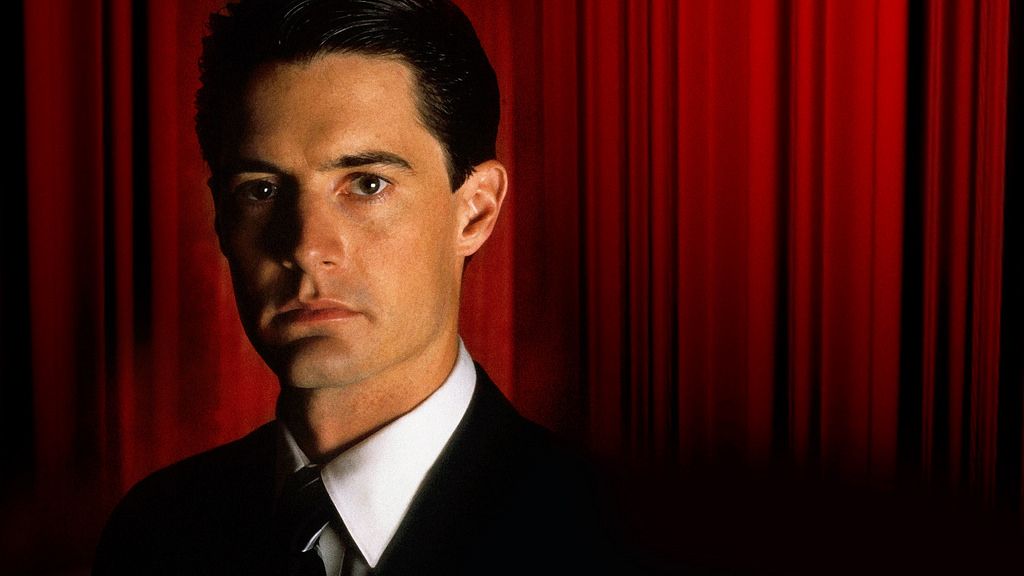

Lynch’s fixation on the insect-ridden underside of the white-fenced, white-faced, post-war American prosperity all but confirmed that the town of Twin Peaks was but a lost highway away from the sordid affairs of his earlier work “Blue Velvet.” The heart of this mystery was yet another of Lynch’s beautiful blonde femmes, except this time she was dead. The FBI agent assigned to resolving her murder had neither the training nor interest in forensics — he skims the corpse for immediate clues with his naked eyes, then closes them, famously transporting himself into the nightmarish Red Room in the first season’s third episode, making clear his preference for dreams, demons and doppelgangers in solving the mysteries of the waking world. In true Lynchian fashion, though, that waking world was never quite awake either.

Despite the show’s reputation as a forerunner of contemporary prestige television, the dialogue in “Twin Peaks” cheerfully creaked and croaked with words spoken less for their real meaning and flow than for their soapy sounds and textures. The tone slipped woozily and breezily from the legalese of a corporate takeover to the melodrama of two teenagers falling in love and back again; the composition of “Twin Peaks” wowed because it was so composed. And it was this quality that vanished when Lynch and Frost did. The last 10 or so episodes are best compared to an unfortunate stain on the velvet, to nuts and bolts flying everywhere in search of a lodestone. The machinery would only reassemble in the last episode of the initial run of “Twin Peaks,” perhaps the most troubling and terrifying hour of network television yet seen, least of all because it would hang the narrative on the proverbial cliff for a quarter-century.

Now, 25 years later, “Twin Peaks” reemerges as “Twin Peaks: The Return.” In many ways, this 18-part series stems directly from the seed of that final episode. If anything, “The Return” signals Lynch’s permanent repossession of his pet project from the network authorities that wrested creative control from him so many years back. Aided this time by collaborator Showtime and longtime collaborator Frost, Lynch directs and writes 18 hours of his famous and familiar surrealism, 10 years after his last feature, “Inland Empire.” But in many ways, something has not come back with the director. For all its innovation, “Twin Peaks” was very clearly designed for broadcast television, each episode having its dramatic beginning, middle and end that, over the course of a season, congealed into the bigger story. “The Return” does not return to this format. It makes total use of the crucial differences that make streaming services like Showtime viable today and consequently feels much more like an 18-hour feature film, split into episodes only out of perfunctory regard for the traditions of television.

This awkward formatting, this formal tension between new and old is the heart of this new and by all accounts final season of Lynch and Frost’s landmark project. What does it mean to return? Is a return really possible? “Twin Peaks: The Return” greets modern audiences among numerous kin. “Fuller House”, “Friends” and to an extent “Stranger Things”: these shows exist to revive an aesthetic and perspective, situating the waning decades of the 20th century as homely days, when housing was affordable, every movie and game was a magical adventure and the world was safe and innocent. Lynch as a filmmaker came to the cultural fore during the Reagan administration, when similar efforts were made to sanitize the fifties. Naturally, these selective chroniclers omitted key experiences: those of queer folk, of women and of people of color. Lynch stands faraway from explicitly engaging with such social issues (he’s far away from explicit engagement in general). But a significant dimension of “Twin Peaks” was the gendered nature of physical and emotional abuse, silenced and sublimated into the stiff picturesque American town. To answer the first question, perhaps “The Return” means the return to the oblique and Lynchian treatment of these issues that earned him and his work such titanic praise in the first place.

But this third season is not just a return to the ideas of “Twin Peaks” — it is the return to the show, its reputation, its place in history and the fandom that has only burgeoned between then and now. So one arrives at an interesting thought: does “Twin Peaks,” a show single-mindedly dedicated to exposing the “Upside-Down” of Americana, need its own exposure and subversion? The answer of the “Return” is a resounding ‘yes’, and the answer to that second question, “Is a turn really possible,” is a doubly resounding ‘no’. “The Return” throughout its run adamantly refuses to answer lingering questions and actively sabotages its own sense of world. The lovable ensemble cast of “Twin Peaks” has been curtailed to one Cooper. Their emotional troubles and extramarital affairs, fester in the margins of the story, occasionally peeping to sadly point out how their subjects are aging without wising. But Cooper himself is punished the most severely. The once incorruptible crusader seeking to deliver justice to the killer of a traditionally beautiful woman is haunted by a doppelganger who looks just like him. Is it him? Is it an evil part of him that he has suppressed for so long because its revelation would disturb the clean distinction between detective and criminal? These are new lingering questions that embolden the aforementioned tension between new and old, a dialectic that threatens to resolve itself in abject, meaningless despair as the possibility of return to any innocence evaporates, episode by episode.

All of this culminates in a two-part finale that resounds in my mind to this day. For all the baggage this 25-year-old show has, it is a recommendation easily made. A subversion of a subversion, television about television. To miss out is to miss out on the possibilities of the medium that can contradict itself.

Comments ()