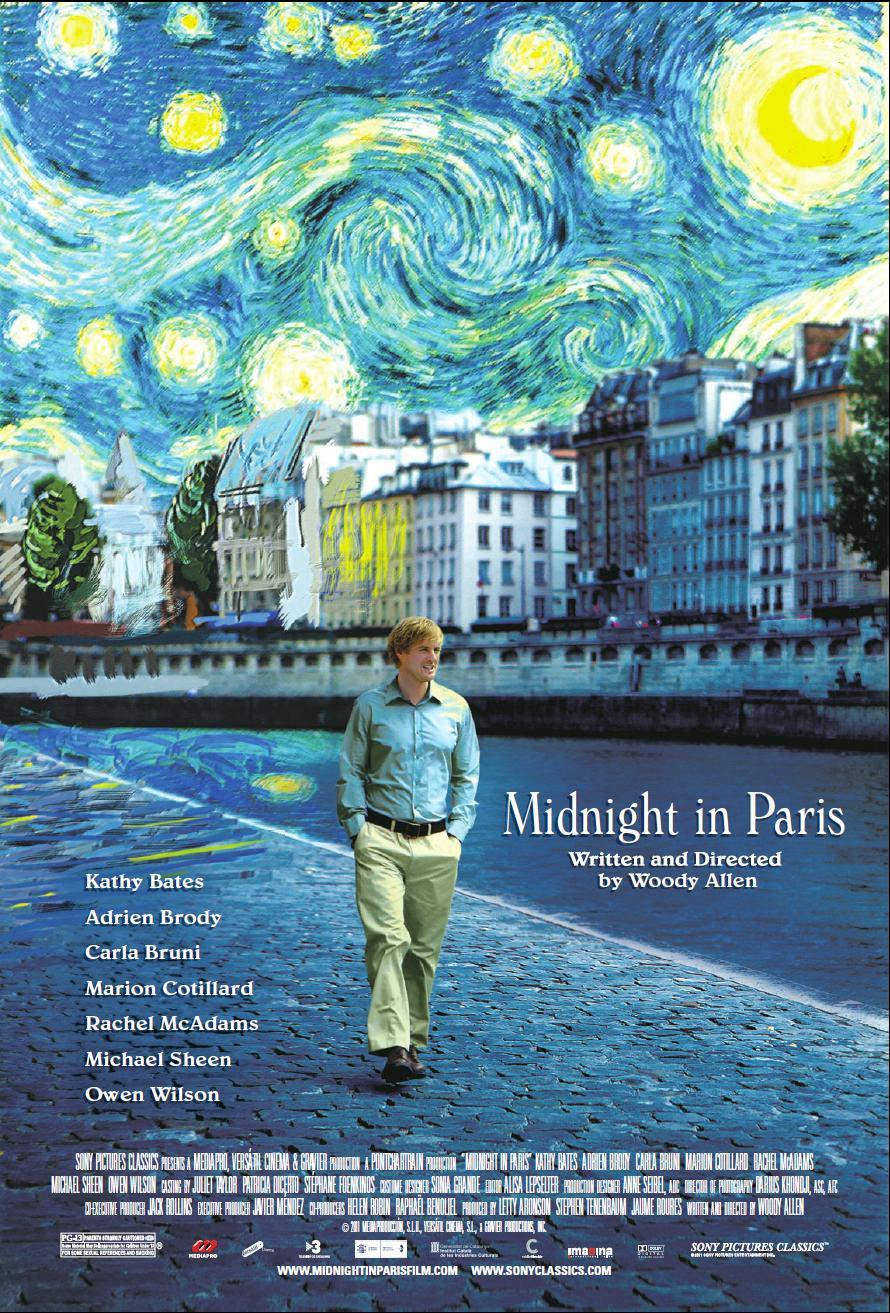

We'll Always Have "Midnight in Paris"

Warm, sentimental and funny, “Midnight In Paris” beautifully explores the clash of nostalgia and reality among fantastical encounters. Director Woody Allen takes us on an exquisite journey through time, spanning across the present, the 1890s and the 1920s — in the City of Light that reeks of wine, music, poignancy and genius, while effortlessly depicting conflicts inherent in the human nature. Only with such grace can the movie truly do Paris justice, and Allen doubtlessly did that, regardless of the extra crème layer on top.

The 100-minute fun ride opens with a heart-stopping montage of Pariscapes — cliché, yet luxuriously so. It is what a travel ad of France should look like, only far more delicate: static shots flip by like vintage slideshows, showcasing the tenderness of street corners, the Eiffel Tower, the Seine, people and, most importantly, rain. With the eyes of cinematographers Darius Khondji and Johanne Debas, we feast on dripping succulence and sensual glimmer. Nesting into Sidney Bechet’s “Si tu vois ma mère” jazz saxophone, we sway into an elegant dream that starts with Owen Wilson’s feverish rave about Paris and how romantic it would be to move there.

A contrast in tone? Maybe. A miscast? Far from it. Playing the film’s protagonist, Gil Pender, Wilson embodies the naïveté and enthusiasm of a Hollywood screenwriter who aspires to write a great novel. Enamored by the city, the fantasy-struck would-be novelist starkly differs from his spoiled Beverly Hills fiancée (Rachel McAdams), who dismisses his idealistic vision of Paris’ ambience and vainly idolizes the elitist pseudo-scholar Paul (Michael Sheen), who snottily rebuffs a Versailles guide played by First Lady of France, Carla Bruni herself.

After declining an evening dance invitation that his fiancée gladly accepts, a tipsy Gil meanders into the night, soon losing himself in myriad alleys. As the clock strikes midnight, an antique taxicab pulls up and a group of festive partygoers call him in. As he enters a bar with his company, Gil soon realizes the smoky, sophisticated bar, studded with literature and music stars like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Cole Porter, is a cultural hub of the 1920s, the era that he has been transported to. Upon hearing about Gil’s endeavors, Fitzgerald introduces him to Ernest Hemingway, who agrees to take Gil’s manuscript to Gertrude Stein (Kathy Bates) for critique. Wide-eyed, Gil rushes to fetch the manuscript, only to find the bar disappearing and himself sliding back to the present.

Over the next several nights, the midnight clock chimes and Cinderella’s pumpkin coach (or the reverse of that, really. No, she does not make a cameo appearance), brings Gil back to the golden age of Paris in his mind, the 1920s of Stein, Dalí, Picasso and Adriana (Marion Cotillard), Picasso’s lover, who appreciates Gil’s novel and to whom Gil is instantly attracted. As his novel becomes more polished, his relationship with Adriana develops and his real-life collision with his dissatisfied fiancée heightens. Gil finds his situation more complicated than ever when Adriana, now the girl of his dreams, is anxious to leave her times and is ecstatic when both of them are transported back to la belle époque, what Adriana considers the “golden age.” A sobered Gil learns that the nostalgic allure is always relative and unattainable, ironically resonating with Paul’s equation of nostalgia with denial. Facing the conundrum, Gil has to make a choice between past and present, his love and rationality.

Allen fine-tunes Wilson’s comedic prowess in Gil, who is bedazzled by dreams but grappling with the bitterness of reality. Gil is endearing, a protagonist we root for from the start. We forgive his follies, social awkwardness and occasional duplicity because of the overwhelming disregard he faces from all those around him, which is subtly yet unmistakably established by the scenes in which he is dragged away from writing by his fiancée to meet her parents, visit tourist spots with her friends and put up with constant sneering and isolation. In empathizing with Gil, we too could not help sinking into the haven he escapes to: the air of love, the fragrance of art and literature and the boisterous Bohemian laughter.

Though surely not as probing as his signature works, Allen knows better than to drench the plot in honey; for a reverie is only a reverie, but a movie embraces more than the remembrance of things past. Indeed, this film is a gentle reminder of the rest of the “dream-come-true” story. But the keyword here is “gentle”: even the confrontation scene — which takes place after Adriana helplessly drowns in the aftertaste of meeting Gauguin and Degas in the famed Maxim’s Paris restaurant — rounds up with soft edges and sentimental luster: no drama, no frustration, only the oozing melancholy choreographed with the strumming tunes of Left Bank guitar.

This is Woody Allen’s world: hopeful, imperfect and saccharine in a lovely way. Maybe the take-home message easily vanishes as soon as we step out of the cinema; maybe it is too palatable, too feel-good. But how can we complain about a gorgeous tour de force of vivid bygone past, wistful eyes and witty dialogues (Gil to T.S. Eliot: “Prufrock is my mantra!” Or on the movie his fiancée’s parents have seen: “Wonderful but forgettable. It sounds like a film I’ve seen. I probably wrote it.”)?

Yes, we get it. The present is dull. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Illusions are fleeting but true self remains. Hemingway thinks making love to a truly amazing woman immortalizes a man (duh). But the solace and pure joy of watching “Midnight in Paris” outweigh the discussion of existentialism, relativism or even time travel. Just cash some euros – 500 francs to buy a Matisse while it is still cheap, just in case you fall into the same ripple in time – and book your flight to Paris for spring break next year.