Old News: This Week in 1920

Each week in Old News, I use a random number generator to select a year in the college’s history and take a look at The Student’s issue from this week in that year.

This Week’s Year: 1920

This week’s Old News takes us to Oct. 4, 1920, exactly 103 years ago. It was the start of the 1920-21 school year, a later month of which I covered in an Old News last March. I had the opportunity to read this issue of The Student from a beautiful bound book of every issue from Volume 53. The book was a graduation gift to then-Editor-in-Chief L. Sumner Pruyne ’1921 from his editorial board. Upon his death, Pruyne gave the book to his son Robert E. Pruyne ’56. Robert’s widow, Carolyn Pruyne, recently bestowed the bound edition to the current editorial board of The Student, which we were delighted to receive. It was particularly meaningful to read from L. Sumner Pruyne’s copy of the newspaper he helped to produce.

This edition of The Student immerses us in the historical context of the early 20th century with casual mentions of things like Ellis Island and a booming Wall Street, in addition to small details about alumni’s post-grad careers and reports on scientific talks. One of the most interesting stories covered the college’s 1920 endeavor to begin a “labor college” in collaboration with local labor unions, which provided night classes, taught by Amherst professors, to both male and female workers in the area.

As I read this edition of The Student, I thought about Amherst’s exclusivity in the 1920s which framed every student competition, class event, and academic activity. Amherst was all male, almost entirely white, and very wealthy — as evidenced by the fact that in 1920, students of certain prep schools had guaranteed admission to the college, no entrance exam required. The student body’s seeming camaraderie and community were fueled by its prejudiced, albeit selectively looser, admission guidelines.

Labor union collaboration: The front page of The Student announced that the college was collaborating with labor unions in Holyoke and Springfield to “offer practical instruction” to union workers at a “labor college.” The article included a list of classes, taught by Amherst professors, that would be offered to members of the Central Labor Union of Holyoke, the Central Labor Union of Springfield, and the Railroad Brotherhood. The classes were offered to both men and women, over 50 years before Amherst became co-ed.

“The labor college is an expression of the belief that a liberal education should be available to all who feel the need of it,” The Student reported. The college would give “the working man or woman an opportunity to meet more intelligently the issues of the day,” and would “make it possible for professors to study labor conditions more directly.”

The catalog included courses about state governments, social psychology (“Special attention may be given to the process by which radicals and conservatives are made”), industrial physiology and sanitation (“A scientific and critical study of the ways in which industrial processes affect the bodies of men, women and children”), and a variety of practical English, economics, and math courses. One class was called “Current Economic Problems” and focused on the “rise of modern industrialism and the wages system” and issues like unions, child labor, “the work of women,” and “the law and its relation to labor.” “Industrial History” offered “a study of how society came to be organized as it is at present, of the differences between its present structure and the way in which it was organized before the coming of the machine; of the rise of business organization and capitalism.”

In her book “Eye, Mind, Heart: A View of Amherst College at 200,” Nancy Pick ’83 described the labor college as an effort on the part of President Alexander Meiklejohn, who, over the course of his tenure, “reshaped [Amherst] into a place known for its its excellence and intellectual seriousness” as opposed to its previous “devotion” to Christianity and its description by the Amherst Student in the early 20th century as “an agreeable, leisurely, semi-educational country club.” Pick reports that many conservative alumni were outraged at the initiative and called it “bolshevist.”

Elaboration on the labor college can also be found in the 1920 pages of another college newspaper: The Harvard Crimson, which on Oct. 15, 1920, reported “Amherst Instructs Labor.” The Crimson article reported that each class would self-govern its business matters, including the required fees. The Student, as quoted in The Crimson, said: “This is the first attempt in this country to work out a policy whereby a college, as such, offers its services for the education of labor.”

Survival of the fittest: Roughly half a century after Charles Darwin published “The Descent of Man,” a “Professor Tyler” gave a speech to students on the concept of the “Survival of the Fittest.” Tyler “showed how the types that were dominant at various periods disappeared or retrograded while man was developing,” and explored a variety of scientific theories about how the animal kingdom had changed over time.

Alum killed in Wall Street explosion: The Student reported that alum Harold Lusk Gillies ’1916 was killed in the 1920 Wall St. bombing, which was carried out via dynamite and a horse-drawn carriage and which is unsolved to this day. While standing in a doorway on Broad St. in New York City, Gillies was mortally injured by the blast. He was memorialized in The Student as an involved community member who made his mark on the Glee Club.

Alumni careers: A selection of alumni updates offered a glimpse into the lives of post-grads in 1920. Reverend Jason N. Pierce ’1902, composer of the song “Cheer for Old Amherst” and other college tunes, moved to a new church in D.C. Meanwhile Owen T. White ’1918 was now vaguely “on the stage in New York City.”

Most jarringly, Harold E. Jones ’1918 was “at present engaged in Psychopathic work on Ellis Island.” This refers to the Psychopathic Ward at Ellis Island, which was added to the island’s hospital complex in 1906 and served as a facility “for the observation and treatment of mentally ill immigrants,” those who had failed medical examinations at Ellis Island and were prohibited from immigrating to the United States. These immigrants were held and observed in the Psychopathic Ward until deportation and return travel were possible.

Student elections: Last week, we voted for new Association of Amherst Students senators; in 1920, students, listed by last name only, were also competing for a variety of offices. The senior class had some elections for more conventional positions like President, Vice President, Secretary, and Treasurer. But they were also campaigning for Class Poet, Class Historian, “Prophet on Prophet,” “Class Prophet,” “Chairman of Senior Hop,” and “Grove Orator.”

Inter-class sports competitions: Most of The Student’s coverage in this issue was devoted to athletics, including competitions with other schools as well as internal competitions among Amherst class years. Seemingly akin to today’s Fall Foliage and Cider Run, the “Annual cider meet” was closely contested between the freshman and sophomore classes, which were competing for a 40-gallon barrel of cider donated by the previous year’s losing class. Also announced were the sophomore-freshman tennis and baseball tournaments, and an inter-fraternity cross country race.

Just to add onto that friendly frat competition, The Student announced that the Treadway Trophy, awarded to a frat with the highest scholastic average, had gone to Chi Phi. That frat had the highest average among its members, beating out the college average. Additionally, a guest alum speaker announced that there would be a prize of 100 alumni-funded dollars for the winners of an inter-class singing contest.

Tax Day: “The student tax of $25 per man with no reductions will be collected this week,” The Student announced.

Admissions in 1920: A text box explained Amherst’s admissions process to all prospective students. In 1920, an entrance exam was held at Amherst in September for applicants. And graduates of certain preparatory schools were in luck, because they were “admitted on certificate without examination.”

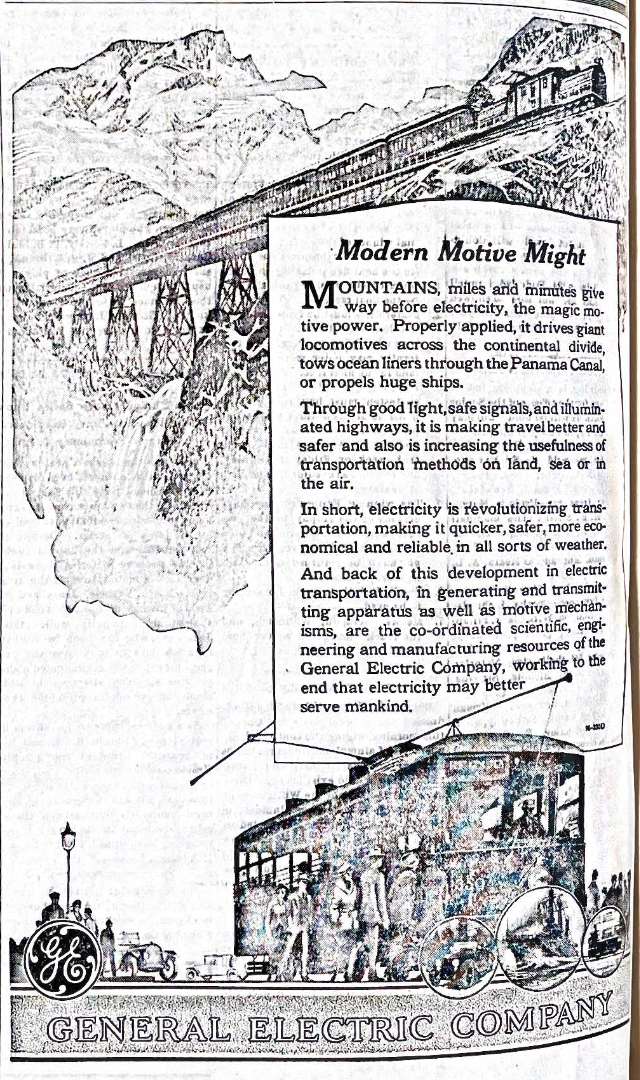

Ads: One ad for General Electric (GE), which boomed in the 1920s, lauded the advances of electricity in transportation. “Electricity, the magic mode of power,” GE wrote in The Student, “Properly applied it drives giant locomotives … [and] tows ocean liners … In short, electricity is revolutionizing transportation, making it quicker, safer, more economical and reliable in all sorts of weather.”

Another ad for college goods, including copies of The Student, was placed by beloved former mainstay A.J. Hastings, which closed just last year.

Pipe company W.M. Demuth and Co. used poetic and absurd-sounding language to entice student customers. It also included a word that then meant “spent” or “depleted,” but which is now offensive in a modern context. “A pipe’s the thing with men,” the ad read, “Under the spell of WDC Pipes men relax, fagged brains are relieved. The specially seasoned genuine French briar breaks in sweet and mellow.”

Other marketing efforts reveal some of the fashion expectations and trends at the time, including one that reads: “FRATERNITY INITIATIONS — Have you ordered your Tuxedo yet?” Society Brand Clothes, “for young men and men who stay young,” advertised new style changes for autumn that men should be on top of. “The long vent in the coat has gone,” they reported, referring to the slit in the back of blazers and suit jackets. Also, “body contours have changed. The high waist line and the pinched-in effect have gone. Society Brand assured Amherst men that they could provide new, fashionable options.