Seeing Double: “What Is Amherst Uprising?”

Six years ago this week, Amherst’s campus exploded in a burst of student-led activism unsurpassed in recent history. Students occupied Frost Library and presented the administration with a list of transformative demands aimed at reshaping racial and social justice on campus. At the time, students hailed Amherst Uprising (as it came to be known) as a pivotal inflection point for the college.

Yet today, the legacy of the Uprising is in danger. Barely anyone on campus personally remembers the Uprising, and those who knew people involved will soon graduate. If students (particularly white students like ourselves) recognize the name, they probably only remember that the Uprising caused the college to replace Lord Jeff with the mammoth we all love.

That’s why this week, we’re going to tell a short story of the Uprising and its legacy. If you haven’t heard of the Uprising, it’s crucial that you do. In our view, much of the Uprising’s power derives from how current students remember it. We will thus cast aside the celebratory rose-tinted glasses common in discussions of the Uprising and look at its unvarnished legacy. The frustrations many students still feel with the college echo those that fueled the Uprising. Addressing those frustrations is only possible with a strong connection to the student movements that came before.

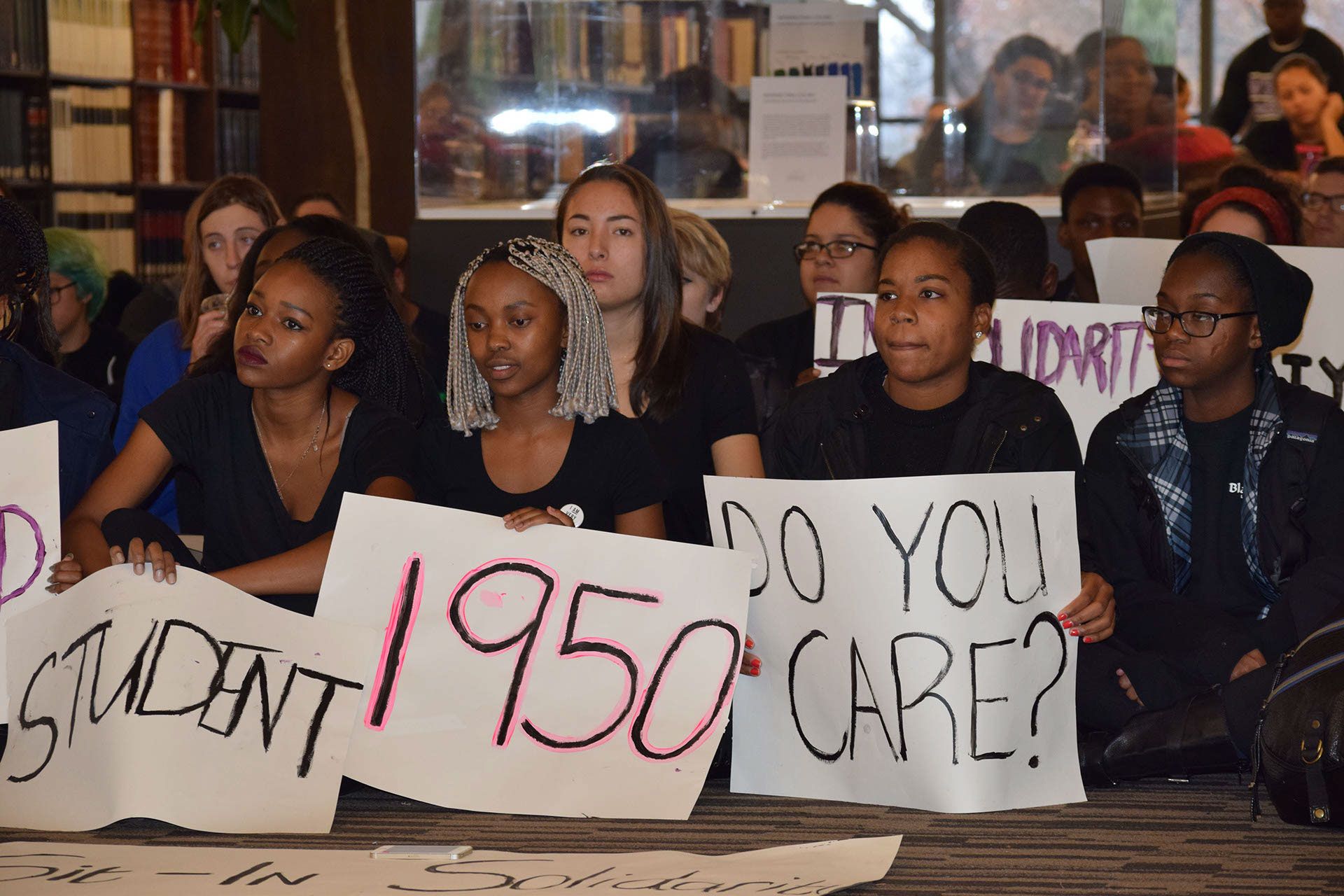

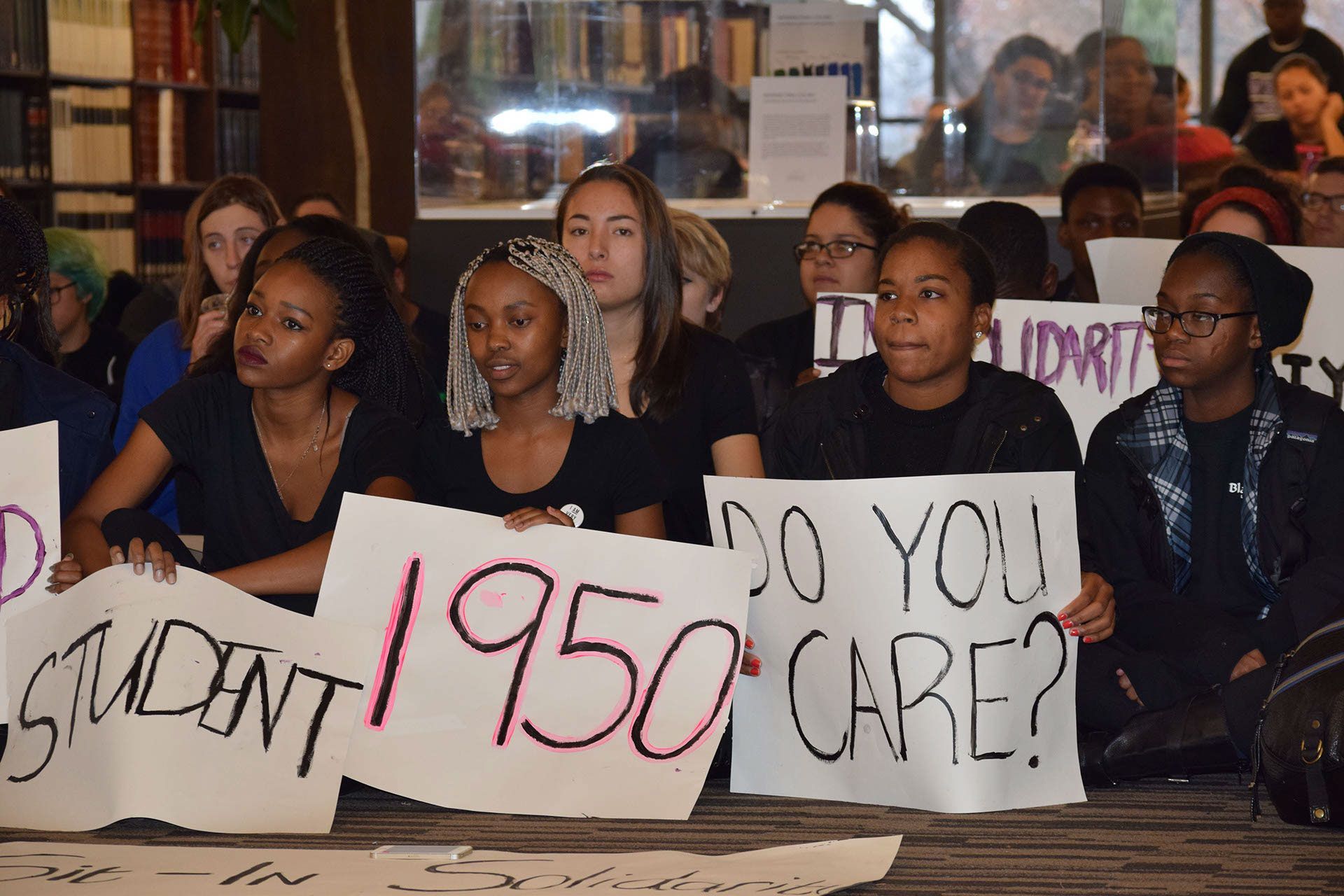

Amherst Uprising began on Thursday, Nov. 12, 2015, as an hour-long Frost Library sit-in. Three Black students, Katyana Dandrige ’18, Sanyu Takirambudde ’18, and Lerato Teffo ’18, organized the event in solidarity with a wave of racial justice demonstrations at Yale, Oberlin, Ithaca, Mizzou, and other colleges. The act touched a nerve, and what began as a few students sitting on the main floor of Frost swelled to a multi-day sit-in involving hundreds of students, faculty and staff.

Frost became a forum for students to express their frustration, anger, sorrow, or confusion at feeling marginalized by the Amherst administration. Fury at issues of equity and justice, long simmering, boiled over. In the words of Kyndall Ashe ’18, “The purpose of [the Uprising] wasn’t like ‘oh let’s do this fun little sit-in and tell [President] Biddy [Martin] we want these things.’ Students are suffering. The number of Black students going on leave who don’t come back is too high; the number of Black students that don’t graduate compared to whites, it is too high; the violence against Black students in certain subfields is too high.”

For days, students remained in Frost, some moving in and out and others sleeping on the chairs and floor of the building. What began as a spontaneous expression of frustration and community turned into a movement. On Thursday night, students drafted their first list of demands.

That list started small, but within a few days, the Uprising organizers compiled a much more substantial list of goals. Many are recognizable from more recent campus protests against racism. They called for mandatory cultural competency training for faculty, staff, and students; anti-racist revisions to the Honor Code; the creation of a Latin American studies major; diversification of the faculty and various staff offices including the Counseling Center; and more funding for affinity groups and theme houses.

The administration’s initial response was tepid. After the first set of demands, Martin “explained that [she] did not intend to respond to the demands item by item, or to meet each demand as specified, but instead to write a statement that would be responsive to the spirit of what they [were] trying to achieve — systemic changes that we know we need to make.” (A statement that, for many students, neatly summarizes the typical administrative response to activism.) In later weeks, Martin offered more specific responses, but the only demand she committed to meeting was the removal of Lord Jeff as our mascot. The college, she promised, would consider additional measures over the next few months.

That is where most accounts of the Uprising end, yet the story of what happened after is just as important — and far less inspirational. Just as Seeing Double began with promise and idealism but (according to our editors) has sunk into mediocrity and routine, the college’s response has failed to live up to its potential.

After the Uprising, the school acted with less and less urgency to meet students’ demands. Until more recent anti-racism protests, the school had met only a handful. And it’s too early to say if the college’s latest actions will work. True, we now have a Latinx and Latin American Studies major, and La Casa has its own space. The college has also made some progress diversifying varsity teams. And initiatives that were inspired by the Uprising, such as Being Human in STEM and the Solidarity Book Project, show that faculty, too, took inspiration from the Uprising.

Yet for each of these important achievements, another goal remains incomplete or unaddressed. The college has hired more faculty of color, but it has also historically struggled to retain them, and new plans for retaining faculty of color are still in their infancy. Over the course of the last five years, the proportion of staff of color in student support departments, such as the Writing Center and Counseling Center, has barely crept up from 17 percent to 22 percent. Mental health resources, particularly for students of color, have remained inadequate. The college has been unable or unwilling to enforce strict rules against hate speech, and only recently updated the student code of conduct to deal with the issue.

Despite not addressing many of the Uprising’s concerns, the administration declared victory. The story of the Uprising transitioned from a narrative of opposition against the administration to part of Amherst’s brand. It became “proof” of the college’s willingness to listen to its students and make change. From the celebratory retrospective offered almost a year after the Uprising by Cullen Murphy ’74, then-chair of the Board of Trustees, to the memorial website operated by the college, Amherst takes pride in the fact that its students called it out. On the five-year anniversary of the Uprising last November, the college organized an hour-long public Zoom conversation between President Martin and five alumni who had organized the Uprising, and two other Zoom events on the Uprising were included in Amherst’s bicentennial celebration.

Right now, Amherst College is the one writing the history of the Uprising — a history that, predictably, goes easy on the administration. Diego Duckenfield-Lopez ’24, the Black Student Union (BSU) historian, summed up the irony: “It was a celebration almost, like how we remember the civil rights movement and glorify it in some ways … It’s a general pattern in how they remember student activism … Then the movement loses steam, and afterward Amherst doesn’t follow through with the rest of it.” Just as the banal, uncontroversial way we commemorate the Civil Rights Movement stands in the way of further progress, the administration’s celebratory commemoration of the Uprising serves only to weaken its cause.

As we see it, the one of the most important achievements of the Uprising was not policy change, but a feeling of power and community among students. Spending days talking about their frustrations, and having their demands heard, was an exhilarating experience. “It was like a fundamental shift in power regarding how Amherst was gonna do things from that day forward,” said Christine Croasdaile ’17, one of the original organizers. Last spring, the Amherst Student expressed a similar sentiment, writing that the uprising has become “deeply embedded in the psyche of the institution and its students.” If students want to maintain this fundamental shift, then we have to make sure that the memory of the Uprising doesn’t slip away.

Today, only a handful of students on campus personally remember the Uprising. Even Martin is departing. In BSU, “[Amherst Uprising] honestly doesn’t come up that much,” Duckenfield-Lopez told us. The Uprising seems to be in danger of being forgotten or relegated to a curio of Amherst College history. As we wrote this article, someone we mentioned it to said, confidentially, “I’ve never actually heard what the Amherst Uprising was.” From an admittedly unscientific poll in the campus group chat, more than half of the 211 students we surveyed said they knew “nothing” or only “a little” about the Uprising. Fewer than 9 percent of respondents said they knew “a lot” about it.

Student power and unity have ebbed after two years of Covid. In response to the public health emergency, the administration has exerted unprecedented power over students’ lives, from kicking us off campus to mandating flu shots to telling us where we can and can’t eat. Our clubs and community traditions have been upended. The pandemic cut us off from our past, and dealt campus activism a serious blow.

And yet, students continue to fight for anti-racist action. In March 2020, after white students associated with the lacrosse team chanted racial slurs at two Black students, the BSU called for a “particular policy to handle threats of racist violence and racist violence.” Immediately after the incident, President Martin sent an all-school email pledging to change the Student Code of Conduct to better deal with racism and bias — one of the Uprising’s demands that never materialized. In response, the BSU outlined a set of demands it called #IntegrateAmherst. They called for a set of by-now familiar changes aimed at making campus a safe, inclusive, and supportive place for Black students. The desire for inclusion and support instead of just diversity was one of the Uprising’s main fuels.

And then a month after George Floyd’s murder in summer 2020, the BSU and two Black alums who ran the Instagram account @BlackAmherstSpeaks, Ashe and Haylee Price ’18, outlined #ReclaimAmherst. It was a new vision for an anti-racist Amherst that often mirrored what students in 2015 wanted: a diverse college staff and leadership; bias training for students, faculty, and staff; the hiring and retention of faculty of color; and a protocol to handle racism. To the college’s credit, Martin responded with an anti-racism plan updated at regular intervals addressing many, but not all, of the demands. Still, immediately after American police killed Daunte Wright in spring 2021, students walked out of classes in what they called #BlackMindsMatter. One of the major demands from this protest could have been lifted straight out of the Uprising: expand and diversify the Counseling Center.

These protests are undeniably connected, and many students on campus see that. “There’s a continuous struggle going on,” Duckenfield-Lopez told us. But it’s hard to keep those memories alive, and hard to impress on new classes the impact that the Uprising had on those who experienced it. That historical awareness is crucial for social activism. As Ellis Phillips-Gallucci ’23, a previous BSU historian, put it, “the current moment can only be made sense of through the past moments, first of all. And so I think that to move forward, we need to first make sure we understand what came first, where we are right now.

When movements forget the past, they’re left without crucial ammunition in the fight for justice. And when students forget the past — our own past as a student body, though we may not have been here — we risk losing that past all together. Once everyone forgets, the power that past movements have to guide, inspire, and strengthen us is gone. There is reason for concern — according to our polling, students are even less likely to know about recent campus activism than they are to know about the Uprising. Almost three-quarters of the 201 students who responded to another poll said they knew “nothing” or “a little” about #ReclaimAmherst.

How are we to remember Amherst Uprising? Certainly not as the feel-good triumph the school portrays in its marketing. The college still struggles with many of the crucial changes that the Uprising demanded. Nevertheless, the Uprising convinced Amherst students of the 2010s that they had power. Today, that success is more in jeopardy than ever before. We won’t ever go back to having Lord Jeff as our mascot, but the sense of student power and community that the Uprising created is breathing its last, ragged gasps.

That’s why it’s our job to tell the stories of our four years to the students who come after — to take seriously the work that we put into growing student power so that we pass the baton without dropping it. The campus protests of the pandemic era, for instance, are nearly forgotten already. If you weren’t on campus last year, then you didn’t see the guerilla posters demonstrating how hard students fought for divestment. And it was nearly impossible to trace the web of Zoom strategy sessions that underpinned much of the #ReclaimAmherst movement.

At a college like Amherst, the student body lives in a state of cyclical amnesia. History may not exactly repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes. If we want future students to push the college to do better, then we should make sure they know how we’ve tried, succeeded, and failed during our time here. Each student is a temporary trustee of our shared work. In passing on the stories of our shared struggles, we turn student activism into something that exists not just for ourselves, our class, or our community, but for Amherst for generations to come.