A Flawed System: The Burden of Service Among Faculty of Color

Toward the earlier part of her career at Amherst, Professor of Black studies, Latinx and Latin American studies and English Rhonda Cobham-Sander typically wrote letters of recommendation for her students in the English department office. One day, as she typed, a white senior colleague came up behind her and peered at her screen.

“Gosh, you’re always writing letters of recommendation!” he said, according to Cobham-Sander. “I don’t think I’ve been asked to write more than one this year, and you’re always writing them.” It hadn’t even occurred to Cobham-Sander that she could be writing three times as many letters of recommendation as other faculty members.

“There are things like that, that you can’t even know for the first few years how much more you’re doing than everyone else, because you just assume that’s what everyone is doing. And then you begin to realize that you’re doing a lot more than other people,” she said.

Though she noted that many white faculty members also write similar numbers of letters, this disparity in workload, she said, is a common experience for faculty of color at the college. In academia, women and people of color tend to bear disproportionately higher burdens of service according to multiple academic studies. Since Cobham-Sander’s arrival at the college in 1986, she has seen a number of faculty members of color leave Amherst because of the pressures and extra workloads attached to working as a professor with a marginalized racial identity. This trend has not gone unnoticed. Extensive research, including reports by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), show that higher percentages of faculty of color report intentions to leave institutions of higher education than their white counterparts do.

These experiences merit a closer look. The Student conducted interviews with nearly a dozen faculty members to investigate possible disparities among faculty at the college. Over the next four issues, The Student will publish an article series examining the many issues that play a role in attracting, retaining and supporting faculty of color at the college. Today, we begin by looking at some of the inequalities among workloads and expectations.

Distribution of Faculty of Color Nationwide, the number of faculty of color at institutions of higher education remains low. The National Center for Education Statistics surveyed degree-granting postsecondary institutions and found that in Fall 2016, 76 percent of all faculty members were white. 6 percent were black, 5 percent were Hispanic and 10 percent were Asian or Pacific Islander. American Indian or Alaska Native faculty members and faculty members of two or more races both made up 1 percent or less of all faculty. At Amherst College, white non-Hispanic faculty members make up 68.1 percent of all faculty. Asian or Pacific Islander faculty members make up 7.8 percent, black non-Latinx faculty members and Latinx faculty members make up 5.4 percent each and multi-racial faculty members make up 2 percent. 3.9 percent of professors identify as international, and 7.4 percent of all faculty were listed as unknown.

Self-identifying students of color, in contrast, make up 45 percent of the student body at the college.

The college has taken steps over the years to prioritize hiring faculty of color. Amherst Uprising, a student-led demonstration in 2015 that protested the treatment of marginalized communities on campus, resulted in a renewed commitment by the administration to diversify the faculty. In 2017, the Board of Trustees raised the college’s Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) cap, allowing the college to hire five additional senior faculty members of color. Senior hires are brought to the college as tenured professors.

Excluding lecturers and visiting and adjunct professors, faculty members are hired into one of two positions: pre-tenure or senior/tenured. Pre-tenure professors, often called junior faculty, typically spend six years teaching, writing and publishing before they are evaluated for tenure. When a professor goes up for review, they compile various documents — their research, student evaluations, published materials, among others — to present to the Committee of Six, which is comprised of six professors elected to the committee. Dean of Faculty Catherine Epstein serves as secretary of the committee, while President Biddy Martin chairs committee meetings. The professor’s department also submits its own evaluations to the Committee of Six. If the committee votes for the president recommend tenure to the Board of Trustees, the faculty member becomes an associate professor. An associate professor can become a full professor later on in their career.

This year, 63 percent of new professors are people of color. Retention at the college, however, is a different story.

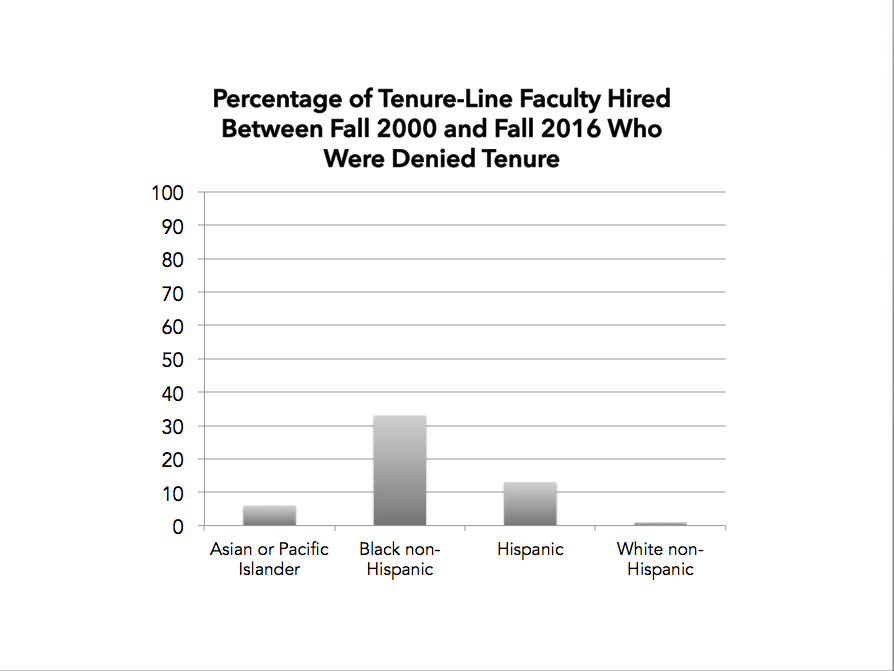

A 2017 diversity and inclusion report obtained by The Student found that of pre-tenure faculty hired between Fall 2000 and Fall 2016, professors of color were denied tenure at significantly higher rates than white professors. 33 percent of black non-Hispanic faculty members were denied tenure, as were 6 percent of Asian or Pacific Islander faculty members and 13 percent of Hispanic faculty members. In contrast, 1 percent of white non-Hispanic faculty members were denied tenure.

The report, an internal document produced by the college’s Presidential Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion and presented to the college’s External Advisory Committee on Diversity, Inclusion and Excellence, identified faculty diversification as “one of the weakest areas of growth at the college.”

“[T]he low number of faculty of color hired is further reduced by high rates of attrition, both due to faculty leaving for more amenable situations, or because non-white faculty are tenured at a significantly lower rate than other faculty,” the report stated.

Burden of Extra Work A focal point raised by multiple faculty members of color that The Student interviewed is the cultural fabric of a predominantly white, elite institution. At such an institution, said Professor of American studies Robert Hayashi, faculty of color have “qualitatively different experiences.”

“We work with students and populations that are often underrepresented, don’t have mentors, don’t have faculty members available to them in the ways that students in the majority do,” he said. “Sometimes our job as mentoring students is advocating for reforms in the institution to better serve students.” He called it “hidden work.”

“Some of the things with faculty of color … is doing labor that’s not necessarily recognized, and that can [be] enervating,” he said. “It can come at a cost in terms of your productivity, emotionally [and] psychologically.” The lack of diversity in the college at administrative levels exacerbates its toll, he said.

Expectations imposed on faculty members are often differential based on an individual’s racial identity. At an institution such as Amherst, all faculty members are expected to participate in teaching, research and publication. Often however, faculty members of color bear the demand of diversity work — “for example, a presidential task force on diversity, committees on recruitment, committees on improving teaching, advising student groups, whether it’s athletics or Asian Students Association or Black Students Union,” according to Professor of American studies Franklin Odo.

“For those kinds of positions, because the faculty of color are so few, they tend to get tapped more often in order for the college to demonstrate that the college is diverse and that they have faculty of color engaged in making decisions,” Odo said. “It turns out that making decisions takes time. That takes time away from students and their research.”

Another source of disparity can be found in levels of participation in national associations. Every reputable faculty member, according to Odo, belongs to one or more scholarly national associations in order to create networks in their field.

“If you become active and a board member, that also takes more time,” Odo said. “If you’re a white scholar, the likelihood is that those particular institutions are huge, and your role is going to be correspondingly small until you become a more established scholar. So the younger scholars are generally spared really, really large obligations as opposed to those of us in smaller associations of color where the likelihood of being on committees is larger. That’s another level beyond the campus where demands of time are increasingly onerous.”

“Given that,” Odo added, “the playing field is not level.”

Cobham-Sander said that external professional work is rarely a choice. For many years, she served on the Modern Language Association’s executive committee of English department chairs. She was also asked to join the external review board of the Social Sciences Research Council Research Committee as “the token interdisciplinary woman of color.”

Studies have shown that women and people of color shoulder disproportionate amounts of emotional labor and service work; multiple faculty members interviewed by The Student spoke about the emotional labor often carried by women and women of color at the college. Additional service often takes the form of committee work within the college.

“That is definitely real when you check multiple boxes, as I do,” said a pre-tenure professor in the humanities who requested anonymity because she has yet to face tenure review. “I have done a lot of committee work that I know people in my same cohort have not done because they don’t check the same boxes.”

“Not only am I on those committees, but then … I’ll do other programming related to [my area of study], and none of that counts for anything,” she continued. “I’m doing it, but it doesn’t count for anything. Because it doesn’t count, I still will be asked to do these other things [like committee work], and you don’t really say no when the dean asks you to be on a committee. And sometimes you can’t say no because you get voted in by the faculty.”

According to a 2018 accreditation review of Amherst College by a New England Commission of Higher Education evaluation team, two surveys of faculty opinion found “fairly widespread dissatisfaction with the service burden experienced by faculty.” In the 2017 survey, 38 percent of Amherst faculty said that “too much service” was one of the worst aspects of working at the college.

When Cobham-Sander first arrived at the college, she had no experience with the nature of race in America. Having been educated in the Caribbean and England, where racism takes different forms, she didn’t understand much of the discourse around “American-style racism” in her first year at Amherst. Soon, however, “I realized what the big deal was.”

At that point, there were so few faculty of color that it felt as if “every black student and almost all the Latino students and quite a few of the Asian-American students were either in my classes or in my office hours or asking me to do things off campus in extracurriculars that involved them,” she said.

“One of my earliest memories is having a Latino student in my office telling me about how his father had been murdered in some way and talking about the very inappropriate things his advisor who was a white professor had said to him,” she added. “By the end of that meeting, when I went home, I was in tears. Who do I turn to? What do I do with this information?”

In her first year at Amherst, the college decided to restructure the Black studies department. In her second year, she was asked to enter “a nonexistent Black Studies department and restart it up.” In her third year, she was completely exhausted, she said. “It begins to have an effect on you,” she said. “You feel like you’re responsible for everybody and everything … As junior faculty, I was doing everything junior faculty is supposed to do and a lot of this administrative institution-building.”

In 2004, then-President Anthony Marx asked Cobham-Sander to serve as special assistant to the president for diversity and inclusion. “It was another kind of trap: ‘we’re going to put you in this position not because you have any training but because you’re a representative,’” she said.

Later, she was asked to lead the portion of the strategic plan devoted to diversity. All of this extra work led to a five-year delay in the publication of her book.

Faculty members of color pointed to this extra service as work not always recognized by the college.

“The fact that more students from all backgrounds come to women and faculty of color from all backgrounds tells you something those professors are doing differently,” Professor of English and Faculty Diversity and Inclusion Officer Marisa Parham said.

“For me, in terms of my work with students, I don’t want to be protected from that,” she added. “I want to be taught how to manage it. But if you know I’m doing all this work, when the institution is doing committee assignments and thinking about evaluation, take that into account.”

This is the first of a four-part series examining retention of faculty of color at Amherst.

Part two — “A Flawed System: Navigating Racist Encounters”

Part three — “A Flawed System: Professors of Color Face Hurdles in Obtaining Tenure”

Part four — “A Flawed System: The Obstacles of Shared Governance”

Comments ()