Town Reparations Assembly Releases Final Report After Two Years of Discussion

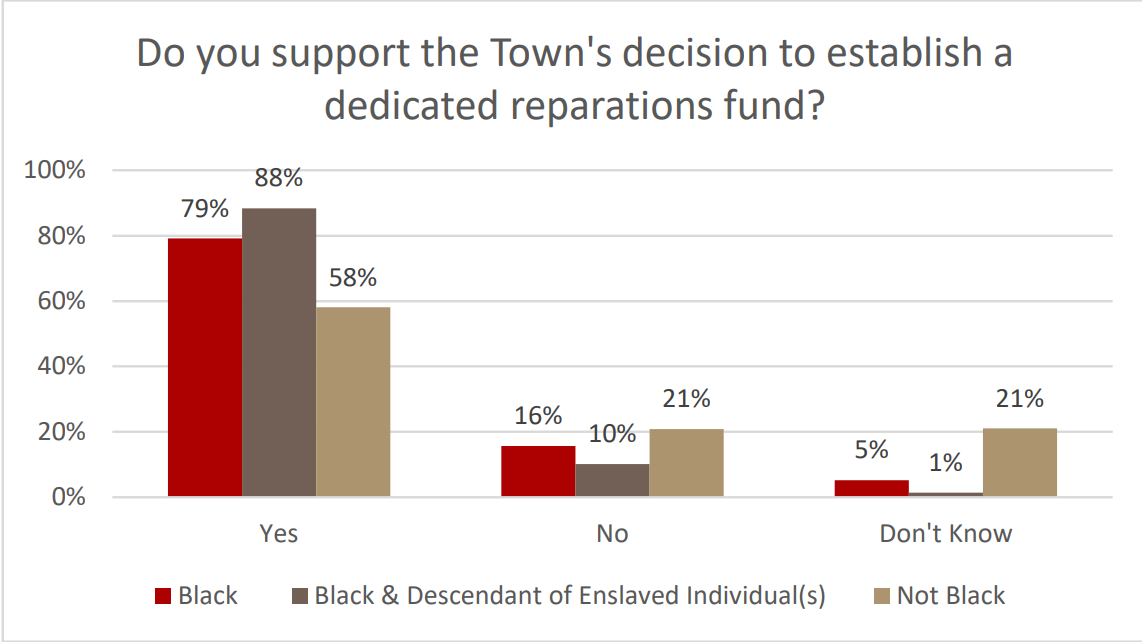

After becoming the second town in the nation to announce a fund dedicated to reparation, the Town of Amherst’s reparations assembly released its final report at the end of September. It includes findings about past and current racial disparities and plans for allocating the $2 million fund.

The town of Amherst’s African Heritage Reparation Assembly (AHRA) released its final report on Sept. 26, addressed to the town council, and will hold a town meeting on Oct. 16 to present its findings.

The final report presents research on historical and current racial disparities, a funding plan for how a successor committee and the town can establish and allocate a $2 million reparations endowment fund, and priorities for the fund: to focus on youth programming, affordable housing, business grants, and entrepreneurial training. The AHRA also includes recommendations for truth, reconciliation, and other remedies outside of the fund.

“The final report is excellent,” said Jennifer Moyston, assistant director of diversity, equity, and inclusion for the town. “Reparations is very interesting because this will be the first time that the conversation has gotten out so publicly.”

All Black Amherst residents are eligible for reparations, with a focus on descendants of enslaved people. The AHRA, which is made up of seven members, also urges other restorative action from non-town entities, including the superintendent of schools, UMass Amherst, and Amherst College.

“Indeed, as the movement for reparations gathers steam across the country, we believe that municipal governments as well as public and private institutions have a role to play in acknowledging and repairing racial harm,” the report reads.

The beginnings of the AHRA emerged in 2020 following a citizens’ petition calling for reparations and the creation of a grassroots movement called Reparations for Amherst, co-founded by Michele Miller, town council member and AHRA chair. This was around the time that the town’s Community Safety Working Group began its investigation into local policing and public safety.

The grassroots movement evolved into the AHRA in June 2021 in the context of a town resolution in December 2020 affirming a commitment to end structural racism and achieve racial equity for Black residents.

The town of Amherst is the second community in the country to establish a fund for reparative justice, after Evanston, Illinois, which established its fund in 2022.

“Being second is significant because it demonstrates that Evanston wasn’t a one-off,” Miller said. “Our country is ready to take on this healing work.”

The report notes that Amherst’s program will influence the national conversation around reparations. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee reintroduced HR 40, a piece of legislation establishing a commission to study reparations and their impact, in January. The act was first introduced in 1989 and has been reintroduced in every succeeding Congress. Rep. Cori Bush also called for $14 trillion in national reparations this June.

“We believe this creates an additional prototype for other towns and municipalities to follow,” said Amilcar Shabazz, an assembly member and professor in the department of African American studies at UMass.“That will ultimately lead toward a national movement to create federal reparations that can truly close the wealth gap and truly bring about the full repair that we need.”

Key Findings

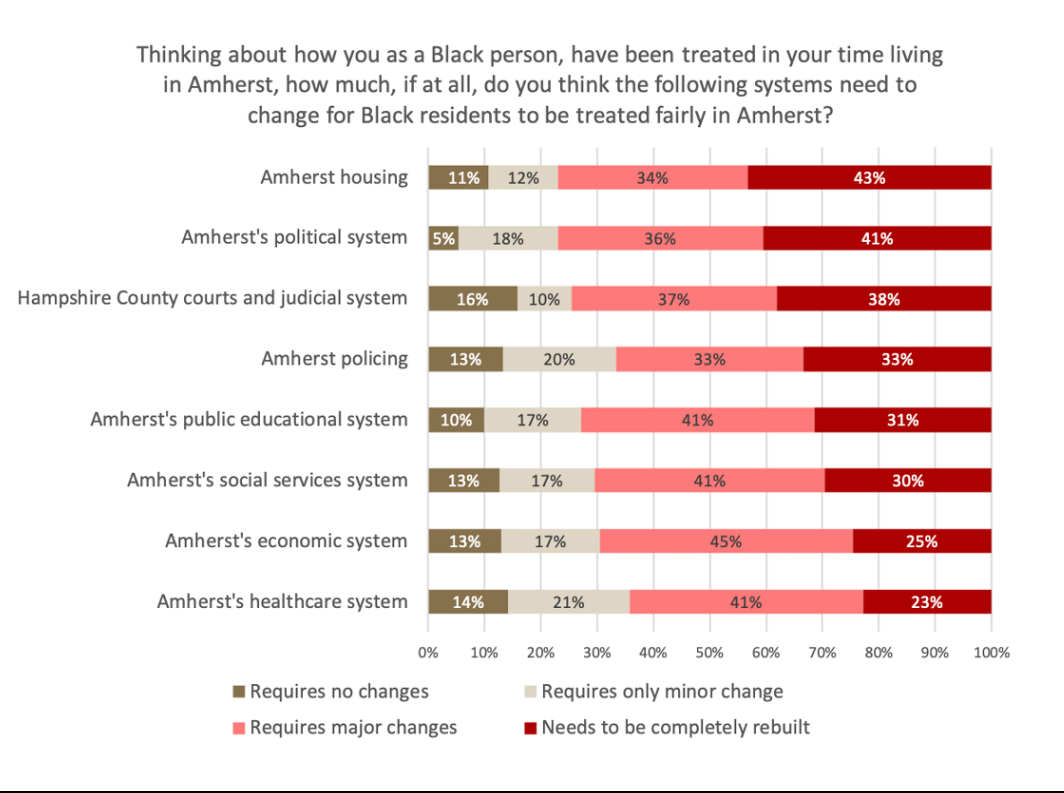

78.4 percent of Black respondents said they had experienced racial discrimination in Amherst, according to a community-wide survey run through the AHRA and the UMass Donahue Institute, the university’s public service, outreach, and economic development unit. The AHRA conducted the survey as a piece of the research process to determine priorities for reparations.

The report researched Amherst history in addition to current racial disparities. It included information about how Boltwood Avenue is named for the descendant of an enslaver and the ways the college benefited from the wealth produced by enslaved people. College trustee Israel Trask held more than 250 enslaved people in his lifetime.

“There’s not a single street in this town named for anybody of African descent. Correspondingly, a lot of the street names are after colonizers,” Shabazz said. “There’s a serious discrepancy there.”

Redlining and public racism are also present in Amherst public schools. In 1990, the NAACP filed a complaint about an undercurrent of racism and harm to students of color.

Current racial disparities in the town prevail in income, housing and discipline. The median income for white families in Amherst is 2.4 times greater than that of a Black family’s median income: $108,500 and $45,464 respectively. Only 1.8 percent of owner-occupied housing in Amherst is occupied by Black residents, who make up 9 percent of the town’s population.

“We’re not participating in homeownership in the town of Amherst in the way that whites are participating as homeowners,” Shabazz said. “We are predominantly renters and that’s rooted in a lot of structural issues like the Black-white wealth gap.”

Shabazz added that disproportionate discipline, especially for young people, was a key finding regarding current racial disparity. At Amherst Regional High School, Black students are disciplined more harshly than white students, and the staff is disproportionately white, the report found.

“Black drivers in Amherst speed less and are involved in fewer car accidents than their white peers, but are stopped and searched disproportionately for ‘investigatory’ reasons, and are 1.5 times more likely than white people to be arrested following a traffic stop,” the report added.

Priorities

Following a community consultation, the AHRA debated what funding priorities would best reflect the Amherst community’s wishes, Miller said.

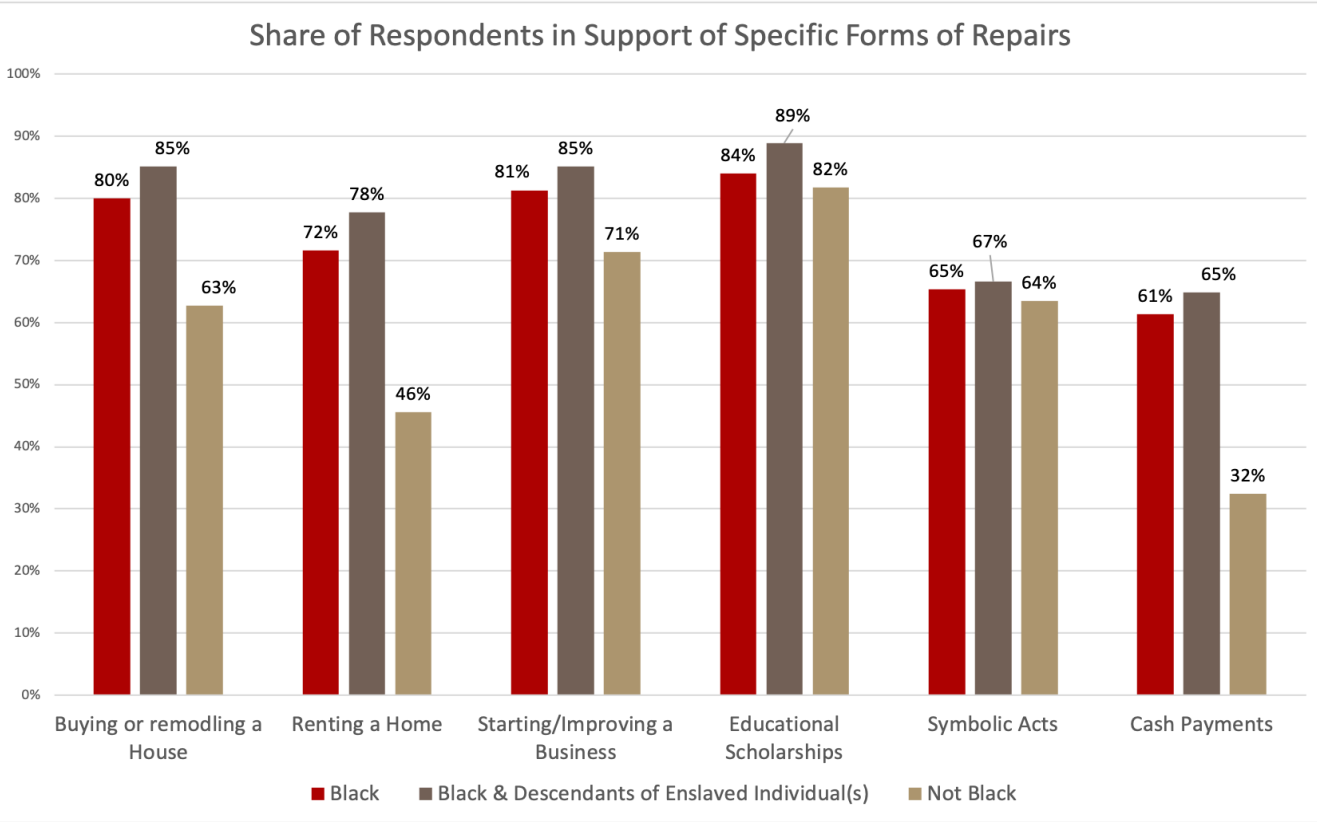

As a result, the AHRA recommended that the fund prioritize three areas: youth programming (in the form of a Youth Empowerment Center, a more expansive curriculum, and educational scholarships, among other initiatives), affordable housing initiatives, and business grants and entrepreneurial training.

Shabazz emphasized that Amherst is a college town, with a majority of the population under 25, so efforts should prioritize the younger generation.

“Amherst College, UMass students, and high school students with enslaved ancestors now have a framework to be heard and responded to,” Shabazz said. “They can all come forward and bring their issues and concerns.”

Funding

The report proposed three funding plans as a response to the town’s commitment to establish a $2 million reparations fund within 10 years.

“We’re asking the Town to accelerate the fund so that we can begin pursuing meaningful initiatives right away and so that we can get to that $2 million commitment within four years,” Miller said.

One option is to fulfill the $2 million immediately by borrowing money from town reserves.

Another option is to devote $100,000 annually from cannabis tax revenues to fund immediate justice initiatives and deposit other revenue into the Reparations Stabilization Fund, which would grow more gradually.

“This financial commitment was based on projected revenue from the cannabis sales tax, which is now trending downward,” the report wrote. “Cannabis tax revenue was selected as a funding source for reparations in part because the historic criminalization of cannabis brought outsized harm to Black people.”

The third option is a middle ground: The town would raise $2 million over four years while depositing a quarter of necessary funds from reserves annually, which would be paid back.

The plan suggests developing ongoing funding by dedicating money from town community preservation and development funds, creating a charitable foundation, calling on private funding, direct cash payments and statewide legislation, charging a permanent successor committee with maintaining the fund, and establishing a Black town assembly.

The Black town assembly would “create a formal space in which Black/African Heritage residents can gather to present, discuss, and vote on reparative justice initiatives, among other issues.”

Continuing Reconciliation and Repair

Besides the recommendations entailed in the report, AHRA provided an expansive list of other forms of reconciliation and repair, including recommendations for non-town entities.

AHRA urged the superintendent of Amherst public schools to “revise history curricula for greater truth telling,” which could include the teaching of AP African American Studies, Shabazz said, in contrast to the Eurocentric education he felt his kids received in the district.

In addition, AHRA said that Amherst College should “Repair and Reconcile With Descendants of Mrs. Frances Brown,” including suggestions for monetary compensation and the production of a documentary about their family’s story. The college acquired Brown’s property amid a clear power imbalance, the report said, and her house became a forest and part of Pratt Field.

“I’m working very closely with President [Michael] Elliott and others to bring the college together with Brown’s descendants to begin the repair process,” Miller said. “The college, at least at the administrative level, has been very open to understanding the harm that [its]actions have incurred.”

In addition, AHRA encouraged considering a town policy for public apology, renaming streets and spaces, supporting the work of Black residents, establishing a museum, dedicating funds to Black-owned Businesses, and addressing health and policing inequities, among others.

“While every community is unique, I hope Amherst’s effort will act as a model for other communities to learn from and be inspired by,” Miller wrote. “I also want to say how deeply grateful I am to the assembly for their dedication, wisdom, and fortitude throughout this process.”

Comments ()