Amherst on the Picket Line: Alumni Writer’s Guild Members Reflect on Strike

The Writer's Guild of America's second longest strike ended after 148 days in late September. Editor-in-Chief Sam Spratford spoke to strike leader Claire Kiechel '09 and other Amherst alumni on why they picketed, what it accomplished, and what's next.

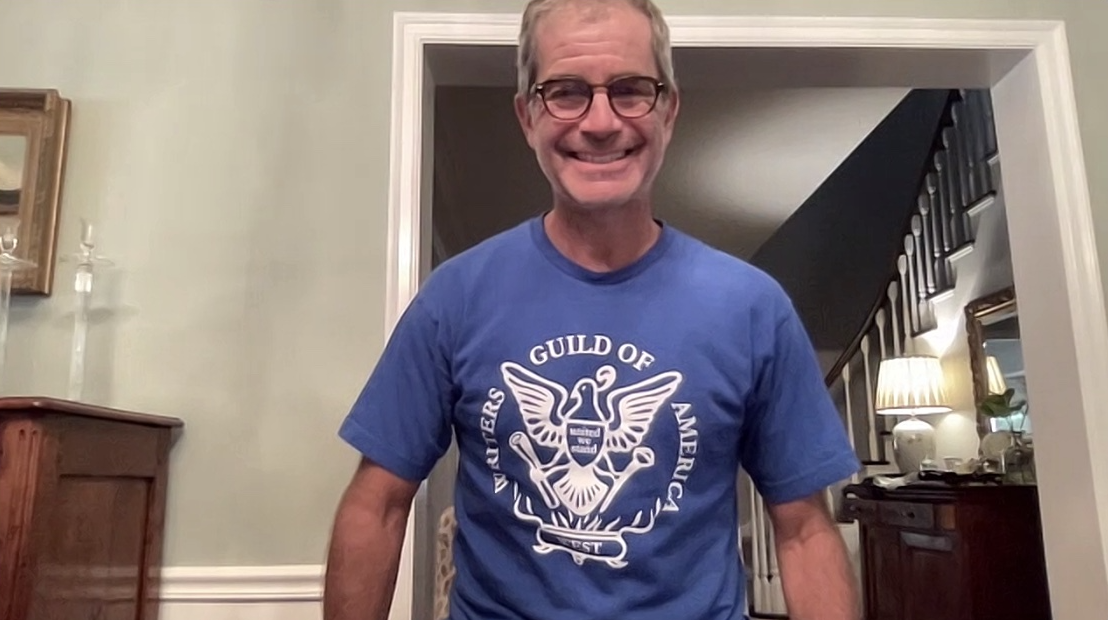

Despite the cyberspace and three-hour time difference separating us, it was clear to me that Vic Levin ’83 participated in this summer’s Writer’s Guild of America (WGA) strike out of more than just obligation — and not just because he was proudly donning a WGA T-shirt on our Zoom call.

“There are moral reasons in addition to reasons of pure survival,” he said of the strike, which ended on Sept. 27, after 148 days, at 12:01 a.m.

Among the many alumni of “The Writing College” who participated in the strike, there is perhaps no better emblem of this ideal than CK Kiechel ’09. When Kiechel moved to Los Angeles in 2017 to start screenwriting, they had $7,000 of credit card debt, an MFA in dramatic writing, and a love for theater. They had been a playwright in New York for six years (“doing stuff off, off Broadway,” they told me) while working in restaurants to help pay off their grad school loans.

But if the financial burden wasn’t enough, Donald Trump’s election in the fall of 2016 made them change course. “I want to do something that doesn’t talk to a hundred white people in a room,” Kiechel remembered thinking, “as … off Broadway theater sometimes is.”

Kiechel always had a passion for writing, but their love for theater was born during their Amherst years.

“I was writing a novella, and then I was like, well, if I write a play, everyone will have to come see it,” Kiechel laughed, then added, more sincerely, “I think I just loved dialogue, and I loved action, and movement, and how people relate in those ways with subtext.”

Between their passion for theater and their concern about its exclusivity, film and television started looking more and more like a beacon of accessible, quality performance art. But it was when they saw the Netflix sci-fi drama “The OA” that Kiechel began to see TV writing as a genuine possibility.

“If this is TV, I can write TV,” Kiechel remembered thinking.

Kiechel landed a position writing for the surreal mystery series, and later moved to “Watchmen,” an HBO superhero drama about an Oklahoma detective trying to stave off a white supremacist attack.

“I actually had a lot of very moving experiences on my shows,” Kiechel said. They explained that, in particular, writing for TV radically expanded their vision of what storytelling could look like.

But for all it provided in artistic fulfillment, Kiechel felt that the screenwriting business was working against them financially. They recalled that, after five months as a staff writer on “The OA,” “I probably came out of there with $5,000 of savings because it cost me a lot of money to move to L.A., and I didn’t even have a car for the first two years.”

Kiechel explained that they weren’t being compensated fairly for the work they were doing — they wrote an episode of “The OA” that they weren’t ever paid for, and they received only a fraction of a staff writer’s normal salary per Netflix’s policy toward first-time writers. Their long-term employment on “Watchmen” — where they wrote for 18 months — was helpful but abnormal. At that time, streaming platforms typically only guaranteed employment in three- or four-month chunks.

Sometimes, though, it was as few as 10 weeks. In the years leading up to the strike, Kiechel told me that employment periods shrunk to six, four, or three weeks as streaming companies shifted closer to a “gig” model at the expense of younger writers like Kiechel.

As I spoke to Kiechel and five other alumni who spent the summer picketing in the Los Angeles unforgiving sun, I realized that their fire came from a desire to save screenwriting from Hollywood — which means, as TV writer John Timothy ’07 put it, saving Hollywood from itself.

The Negotiation

The material gains that the strike engendered were “exceptional,” wrote Jen Suh ’08, a policy analyst and researcher for the WGA, in an email to me. She translated some of the wins codified in the Guild’s new contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) into plain English for me. Among them are viewership-based residuals [and] streaming data transparency, which will help ensure that writers partake in the success of their work for streaming platforms; staff writer script fees, so that the whole writer’s room (rather than just the “lead” writer, called a showrunner) is rewarded for their work; and AI restrictions that will guard against the displacement of creative work to computers.

Some of these have been goals for the Guild for years, Suh wrote, but to no avail: “Most of the gains we achieved in negotiations were called ‘non-starters’ by the studios five months ago.” She emphasized that “the strength, unity, and resolve demonstrated by Guild membership is largely responsible for transforming those ‘non-starters’ into reality.”

Everyone I talked to framed this negotiation in existential terms. “This was a fight to maintain the potential of writing as a career,” Timothy wrote to me. “It felt like the AMPTP wanted to, in the long run, turn us all into gig workers. They wanted shorter contracts, fewer guarantees.”

For writers earlier in their careers, the stakes were even higher. “We were nearing a breaking point where screenwriting would become so unsustainable that it would become entirely the world of the already monied,” Timothy said.

Levin is a writer, producer, and director who created 90s drama series “Mad About You” and “Destination Wedding,” a rom-com co-starring Keanu Reeves and Winona Ryder — in short, he’s made a name for himself in L.A., and feels for the unique challenges that younger writers face.

Levin told me that the number of movies and TV shows has grown enormously since the advent of streaming. Combined with the “inflationary pressures” on the cost of living in L.A., as Levin put it, the WGA also reported in March that 98 percent of staff writers — the position that many young writers start off in — were working for minimum pay, representing a 23 percent decrease over the past decade when adjusted for inflation.

It’s become much harder to establish yourself as a young writer in Hollywood, Levin said, and this also means that the future of motion-picture art — the egalitarian, immersive storytelling that attracted Kiechel to L.A. in the first place — is in question. As Timothy put it, if it’s only the “already-monied” sitting at the writers’ table, that “could only have deleterious effects on the types of shows and movies that got produced.”

It’s also about keeping the flame of creativity alive. “If you’re in a panic about whether or not you can pay your rent,” Levin added. “How are you supposed to take artistic risks? How are you supposed to do your best work? How are you strong and stand up for what you believe in?”

Kiechel told me they spent years writing in these poor conditions, but didn’t even realize that there was an alternative until this summer. The solidarity they experienced during the strike restored their faith in the dream that Hollywood once represented to them, and so many others.

"What the strike taught me is how capable I am and other writers are,” they said. Then, more firmly, they added, “There’s another way that we actually can do this.”

The Strike

As Kiechel’s comments suggest, the strike was more than just a means to an end — the months writers spent picketing in the blazing sun of the L.A. summer renewed their sense of collective strength. “I think many of us realized … that a union doesn’t become a union until you have a collective action like a strike,” Kiechel put it succinctly.

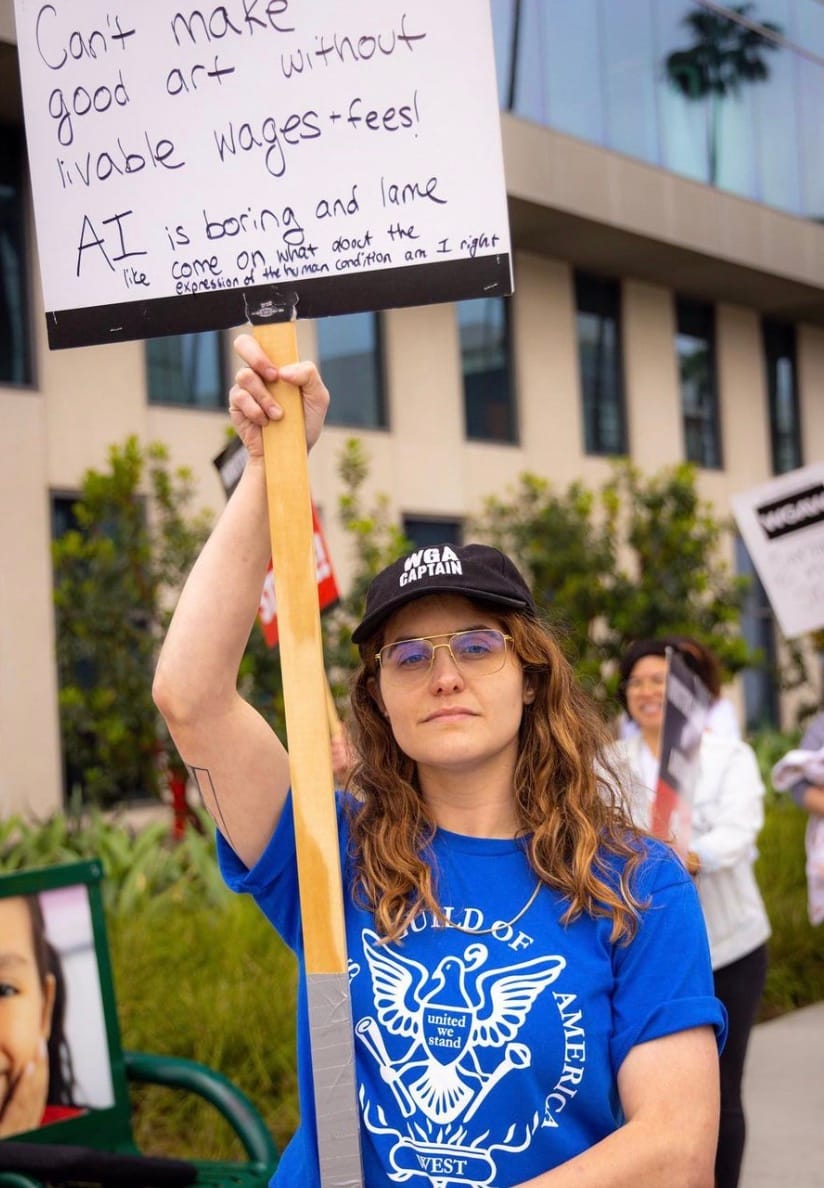

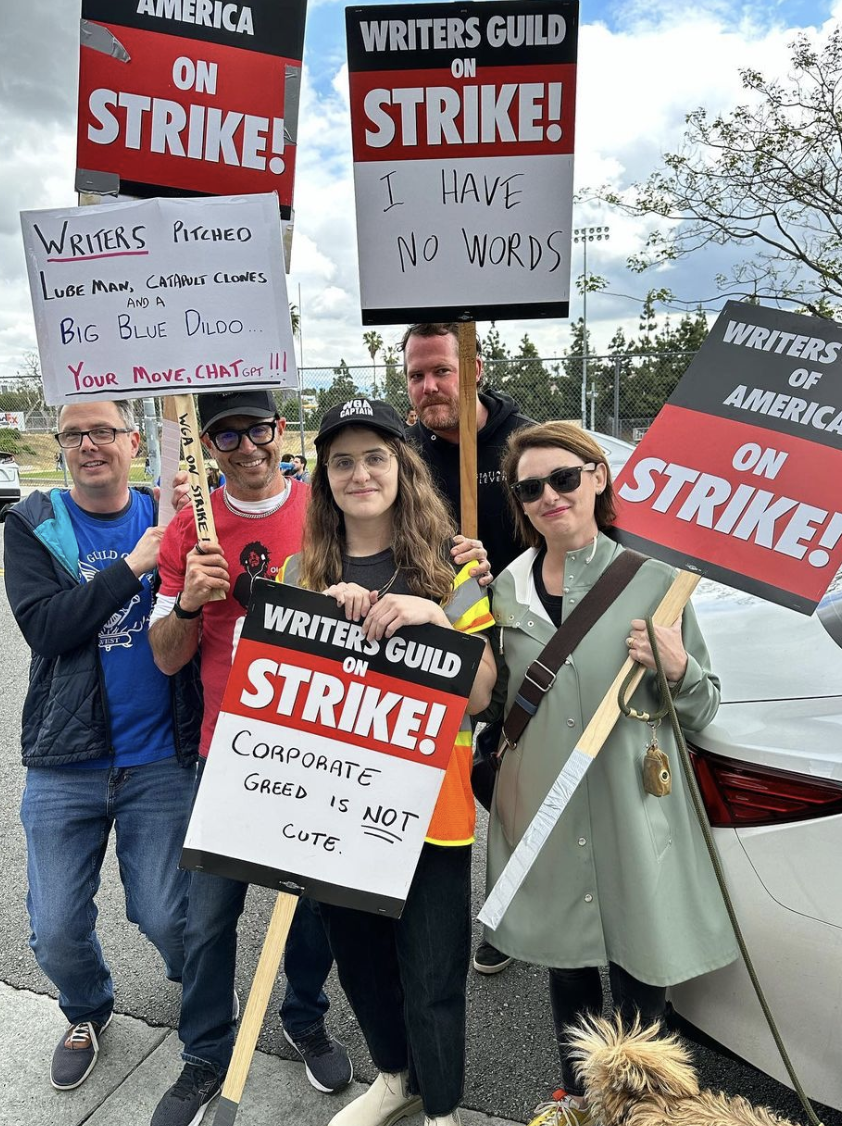

Kiechel was a strike captain at Netflix, which they called the “Big Bad,” referring to the platform’s pioneering and large influence on streaming industry practices. Kiechel already held the role of union captain in their writers’ room — a union liaison that every writers’ room is required to have — and so when the strike began, they naturally took on the new role. Their day-to-day duties involved checking people in on the picket line, making sure they had food and water, organizing themes and activities, and generally “keeping peoples’ spirits up” — “like [a] camp counselor,” they laughed.

But over the course of the strike’s 148 days — the second longest in WGA history, just shy of 1988’s 153 days — they took on larger organizing projects and challenges that no camp counselor (hopefully) would ever have to deal with.

For example, Kiechel told me that many writers, especially in the latter part of the strike, were feeling the financial strain of the months they had spent out of work. Once the challenges of the daily picket were smoothed over, Kiechel spent a lot of time organizing “assistance and outreach in helping WGA members apply for grants, loans and financial aid,” from the funds the union has saved up for situations like this. “Also helping those who were eligible apply for unemployment and food stamps — in California unlike New York there is no employment for striking workers.”

Communication efforts were also crucial. “We set up tents on the lines so people could come ask questions, organized community teas and film screenings for people to gather at, paired accountability buddies, and wrote up a document of most frequently asked questions (e.g. what if I’m behind on member dues but I need to apply to the fund), and tips for keeping calm about the whole process,” Kiechel explained.

If you visit Kiechel’s Instagram or Twitter, you’ll see podcast and newspaper interviews, ardent commentary and updates on the strike, and pictures of them smiling with signs and other writers on the picket lines. Kiechel’s reputation as an enthusiastic strike leader came up in my conversation with Janet Lin ’97 — a writer on Netflix’s hit period drama “Bridgerton” — before we even exchanged introductions: “Oh, I know Claire!” she exclaimed, when I first cold-emailed her.

While cultivating inner solidarity, organizers also had to keep up the “wellspring of community support,” in Kiechel’s words, that the WGA had to draw strength from. Besides this being the first time since 1963 that the actors’ union SAG-AFTRA joined the WGA on the picket lines, everyone I spoke with expressed gratitude for the solidarity of the Hollywood teamsters and the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). “These pickets only worked because of the solidarity of the amazing members of IATSE and the Teamsters,” Kiechel wrote in a follow-up message to me. “By shutting down [the physical aspects of production] we were able to put pressure on the companies who could not go on with business as usual.”

In the middle of the summer, Kiechel spent three weeks in New Mexico organizing the largest picket outside of California and New York City, America’s main motion picture hubs. Among other things, they cultivated relationships with IATSE leaders to “better understand the production landscape we were entering,” and built lines of communication with crew members “so that we could get inside information about each production … and increase solidarity.”

Susannah Grant ’84 — a negotiator during the 2007-8 strike and a former member of the Board of Trustees — also emphasized the fantastic job that higher-up WGA leadership, like Negotiating Committee Co-Chair Chris Keyser, did rallyinging the rank-and-file. “We happen to have a really smart, really wonderful speaker [in Keyser] who has kept us unified in solidarity,” Grant said. She enthusiastically directed me to a video message that Keyser released on Labor Day, adding, “I can’t say anything better than he can.”

Again, Grant isn’t just speaking about internal solidarity. “I think the Guild was pretty good at communicating … [that] what’s happening in our industry had happened or was threatening to happen in so many industries in our country,” she said.

“All these publicly held companies are sort of a slave to their quarterly reports … increasing their profit and reducing costs. And eventually that ends up reducing labor costs to the point where people who used to be able to make a living at this couldn’t anymore,” she continued.

“The fact that we accidentally found ourselves in the midst of … an intra-industry union movement,” was crucial to the WGA’s success, Levin said.

“What we do is so much less necessary than what they do,” he continued. “But we had Amazon drivers at our rallies. We had UPS drivers at our rallies. They spoke to us as though we were their brothers and sisters. And that meant a lot to us, you know?”

The historical moment was important in more ways than one. As Kiechel put it, “Hollywood is a very unique place because it was one of the few places that was actually built by union power … These studio bosses, like Walt Disney and Louis B. Mayer [of MGM] paid people enough to have middle class existence, not because they wanted to … but because IATSE had a union, and then the WGA was able to have a union,” they said. It’s thanks to the tradition of labor solidarity that “the wealth from the movie industry, a unionized industry has been with us from the very beginning.”

Besides being a self-proclaimed history nerd, part of Kiechel’s organizing involved researching the WGA’s history “all the way back to the 1920s, so that I could speak and write … about the context for this battle and what members of previous generations had sacrificed and given for us to be here now.”

The 1960 strike in particular kept popping up in my conversations. Apart from being the last time SAG-AFTRA and WGA struck jointly, it birthed the healthcare and pension that so many writers rely on today. The 1960 strike also won writers residuals (the success-based payment system that the 2023 strike was trying to adapt to the streaming ecosystem), but they gave up all of their backlogged payments to establish these funds.

“The people who made that deal were walking away from a great deal of money that they might have pursued for themselves,” Levin told me, “in exchange for assuring that this income would be there for people in the future and, and crucially for younger people.”

“There’s a long tradition in our guild of trying to pay it forward, of trying to take care of the younger people,” Levin said. “And that’s very much what this strike was about.”

The Future of Hollywood

The WGA’s gains were exceptional, but Levin told me it’s no time to become complacent. “The job is never done because technology and the business change and evolve on a moment by moment basis,” Levin said. Just as their 1988 counterparts had to fight for residuals on made-for-cable products, and 2001 writers demanded compensation for internet rentals, the unpredictable development of technology continually creates new cost-cutting loopholes that take forceful collective action to close. “We need to be aware that five minutes from now there could be another problem as apocalyptic as AI or another form of AI that’s even more difficult to contend with than generative AI,” Levin added.

Enforcement is an even more immediate worry, as Grant told me. “Enforcement is always hard because these companies try and cheat you every which way,” she said. “They’re really late in paying [and] they’re really shifty in their bookkeeping.” She told me about a friend who wrote and directed a movie that cost $17 million and made $90 million in its original box office sales — yet, “According to their [the studio’s] accounting, it’s still [in the red].”

If the level of solidarity this summer demonstrated is any indication, the WGA will be a strong contender in these fights. “Pick really fostered a sense of ‘in the trenches’ solidarity,” Timothy said. “In a lot of ways, [that was] the biggest mistake the AMPTP made.”

Suh, the WGA policy analyst, did not mince her words when I asked for her takeaways from the strike. “The demonstration of inter-union solidarity, at this scale, is new, and not to be dramatic, but I believe it marks a new chapter in the story of Hollywood labor,” she wrote to me.

“It’s possible that I’m in a Los Angeles bubble, but I believe the public support the writers’ strike has seen over the past 5 months has boosted a regenerating labor movement,” she continued. “They’ve shown that collective action works.”

In addition to seizing onto this momentum in their organizing, Kiechel is hoping to take the movement from the streets to the screens. “We still operate in such an individual protagonist story arc … [and] it’s going to change a lot of the stuff around labor, around this economy, [and] exploitation … if we don’t also fundamentally change the ways that like what, how narrative and story arcs work.”

Hollywood needs to depart from the old formula, “a bastardization of Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey,” as Kiechel put it, toward “a group narrative … where everyone has their own little talent, and then [they] all come together and make something happen.”

“I think that is what maybe after the strike feels most personally inspiring to me,” they continued, “to try to figure out ways to tell a collective story.”

Editor’s Note: Having trouble accessing any of the linked reporting? They say that if you encounter a 10 foot wall, you should find a 12 foot ladder(.io)...

Comments ()