An End to the Doom Scroll: How Students Stay Productive on Devices

Students’ devices offer both essential learning tools and endless opportunities for distraction. Staff Writer Mira Wilde ’28 highlights creative solutions to combat distraction in an effort to maintain their focus and reclaim time from their screens — whether through apps or physical distance.

In any given study spot on campus, you’ll likely find students using their computers for both work and procrastination — glued to their device, stuck scrolling to avoid imminent deadlines.

Screen time is a double-edged sword for college students, offering both essential tools for learning and endless opportunities for distraction. Students are tethered to their devices for their academic work now more than ever. But social media, games, and streaming platforms are only a tap away, interrupting study sessions and creating cycles of procrastination.

Many students at Amherst have found creative solutions to combat distraction in an effort to maintain focus, balance mental health, and reclaim time from their screens and devices — whether through apps or physical distance.

Talia Ehrenberg ʼ28 discovered her go-to productivity app, Forest ($3.99 on the app store), back in middle school, and it has been helping her stay focused ever since. The concept is simple, yet effective. “It’s an app where you can use either a stopwatch feature or a timer feature to plant flowers and trees … you get more trees the longer that you focus,” Ehrenberg explained.

But, there’s a catch — if you open another app during your focus session, the tree you’re growing dies. Ehrenberg acknowledged that this feature of the app can be beneficial to those who need a harsh limit, but said, “I personally have turned that feature off … I do not want dead trees because that’s not fun and cheerful, and this is really about making studying fun and not stressing me out.”

Ehrenberg also appreciates that she can match the flora in her app with the trees and flowers that are growing outside. “I do think that this app actually does maintain some sort of connection to nature and the dopamine that’s associated with nature for me,” she said. “The same joy that I might get from a garden, I can get a small amount of [from] these colorful trees that are growing.”

While Ehrenberg largely uses Forest for distinct periods of productivity and data collection, other Amherst students have sought out treatments to their phone usage based on lifestyle changes.

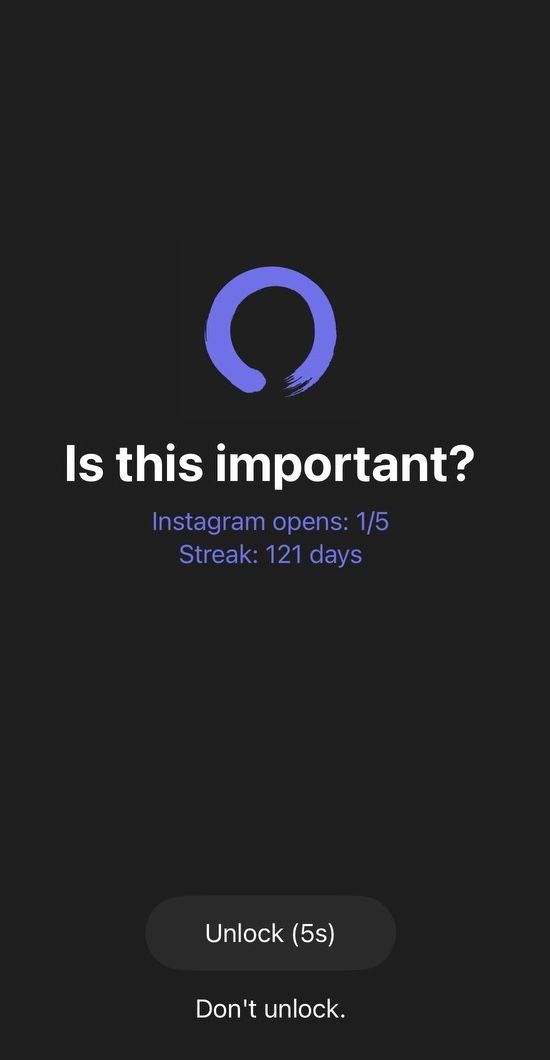

Charlie Jenkins ʼ28 started looking for an app when she noticed how much time she was wasting on her phone on social media, even when she tried deleting certain platforms. Jenkins uses ScreenZen (free on the app store), an app that allows you to select specific apps that you want to limit your screen time on. “On ScreenZen, it hits you with this little message when you open Instagram. It says, ‘Is this important?’” This manufactured moment of reflection forces Jenkins to ask the questions: “Is what I’m about to do important right now, or is it a habit of me opening my phone, or is it just [that] I need something to do? And could I do something about it?”

ScreenZen only allows Jenkins to open her restricted apps five times a day. After she unlocks the app, she gets 10 minutes before she sees the same screen asking “Is this important?” Users can predetermine how many opens per day they can have on their restricted apps, as well as how long each of those uses will last. There are also options to customize the question prompt, to be forced to wait more time before unlocking, and even to do math to unlock the app.

Jenkins said she is incentivized by the streak that the app keeps for its users, which increases every day that she goes onto her restricted apps five times or less. Jenkins shared: “As the streak got higher and higher, I wanted to maintain it. But also, I just felt the need to go on [my phone] less.” Jenkins’ streak is now in the hundreds, and she does not plan on breaking it anytime soon.

While both Ehrenberg and Jenkins found apps that work for their focus and lifestyle needs, Riley Donat ʼ28’s solution is more material — and more extreme. Donat resolved to use “a little gray brick and it has an Apple card reader in it. And you download this app called ‘Brick.’”

Through the Brick app, users can either choose which apps they want to be allowed or which ones they want blocked. Then, once a user taps their phone to the physical Brick (similar to the technology in tap-to-pay card readers or Apple Pay), the mode that they have set goes into effect. Donat, describing the app, said that “when you try and open the app and it just says, ‘This is a distraction. Your phone is currently bricked. To access [the app], tap your brick.’”

For Donat, the physical nature of this approach is especially helpful. “I leave [the Brick] in my dorm and then I don’t go on social media or anything that I block all day. Not because I have discipline, but because I’m not physically there. I cannot physically scan it.”

Donat, like Jenkins, started using her Brick ($49) for a lifestyle change during the summer. “It was such a pattern of me sitting in my bed for hours after waking up, scrolling, unable to move and get out of bed,” Donat said. “I was like, something’s gotta change here … it was a horrible start to my day.” As a first-year student, Donat was also worried about the transition to college and balancing course load, social time, and screen time: “I wanted to be present, I wanted to actually do good work, I wanted to interact with people more than just sitting on my phone.”

The Brick was the perfect solution for Donat. “When I can remove the endless scrolling from the phone, the phone becomes less fun, and I actually do my work … It’s truly changed the quality of my life. Screen time has genuinely gone hours down.” Donat went on to describe how the Brick changed how she makes use of her time, describing the result of her usage as “more productive procrastination. If I’m going to procrastinate a paper, I better clean my room instead of scroll for an hour and do nothing.”

Jenkins and Ehrenberg similarly reflected on a changed sense of productivity as a result of their apps. For Jenkins, “instead of going on my phone, I’ll choose to do something else,” citing specifically more time for creative activities like painting and collaging. “I would actually do something good for my mind instead of taking my downtime and just scrolling,” Jenkins added.

Comments ()