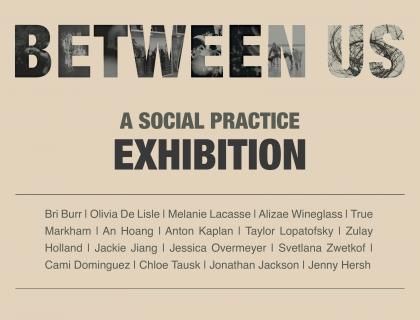

“Between Us” Explores the Confluence of Art and Social Practice

Jonathan Jackson ’17 and Hoang Thu An ’18 participated in Visiting Professor Amanda Herman’s Five College advanced art seminar course: “Make it Public: Art and Social Practice” about socially engaged art. The course has students from all five colleges who were chosen by the art departments at their schools for their exemplary work. For the course, each student proposed and implemented an original social practice art project that explore themes of identity, gender, race, mental health, human perceptions, feelings and more. The exhibition is currently up in the Eli Marsh Gallery in Fayerweather Hall and will stay there until Dec. 14. I was able to speak with Jackson ’17 and Thu An ’18 about their projects.

Jackson:

Q: How would you describe your project?

A: “The Portrait Exercise” was a simple collaboration between myself and two participants that was centered around discussions of photography and image making. I was attracted to “Make it Public: Art and Social Practice” because the course focused on socially engaged art making. As a photographer and lens-based artist I feel that the work that I’ve been creating is solitary. The images presented within our class exhibition are the result of on-going conversations about portraiture with Truth Murray Cole ’20 and Sahara Ndiaye ’20.

Q: How did you come up with your project subject?

A: I knew that the project would be an extension of my own studio practice. It was our instructor — Amanda Herman — that led me to the idea of just facilitating a simple image exchange and dialogue for the class.

Q: How has your project developed throughout the semester?

A: First, I had to determine scale. Would this be a project open to the Five College Consortium? How many participants made the most sense? When it came down to it, I decided to just work with those within the Amherst community. I invited two participants who demonstrated a strong interest in image making. After we had an initial meeting we went straight into making images for the exhibit, both separately and together.

Q: What is your intention/main goal with your project? What effect do you hope it has for your audience?

A: For myself, the project is successful on a conceptual level. This has been my first time ever seeking collaboration for an artistic project. Although I doubt that this style of creative participation will become a major component of my continued work, it has been an interesting complement to my studies.

Q: What was the most challenging part of your project?

A: The project presented some interesting editing and installation challenges towards its conclusion. This was my first time printing digital photographs on a large scale.

Thu An:

Q: How would you describe your project?

A: The Happiness Project is a socially engaged art project, which relied mostly on public participation and contribution. During the first phase of the project, I installed boxes of happiness in the most public places at Amherst: the one and only dining hall Valentine, Frost Library, Keefe campus center, Fayerweather and Limered tea house. Together with these boxes were pencils, crayons, paper and the prompts “Draw Your Favorite” and “Put It in the (Box of Happiness). The drawings collected from these boxes were put together, making up a giant wall piece during “Between Us” exhibition. I called it the “Wall of Happiness.”

Q: How did you come up with your project subject?

A: As an artist, I strongly believe that there is an artist in all of us, and that drawing is most effective and common way of visual communication. As a person, I deeply care about happiness. I am uneasy to see how stress has been overflowing on college campuses and how easily we stop appreciating the smallest joy. Such concerns and belief inspired the Happiness Project.

Q: How has your project developed throughout the semester?

A: I initially planned to put up big canvases to attract public drawing. However, due to the high expense, I adjusted the scale to small drawings and made boxes of happiness. In retrospect, I felt that the box worked really well in that it offered some kind of privacy that giant public canvases could not afford. During the first day of the installation, I did not get as many responses as I wanted to. I talked to a friend whom hadn’t known about my project in advance. Thanks to his comment and suggestion, I adjusted the box and added explanation next to it. Participation boomed after the small, yet significant tweak. I collected the drawings every night and let the boxes out for about a week. I took off my box just before the election ( I didn’t plan to, just a coincidence) so I didn’t get many political related responses.

Q: What is your intention/main goal with your project, what effect do you hope it has for your audience?

A: At the beginning, I had multiple goals for the project. The most important goal was to motivate people to draw and wake up the artist within them. I aimed for around 100 drawings for the exhibition. The second goal is to bring more attention to mental health — the importance of taking life lightly and being able to appreciate. I hope that these boxes prompted everyone to stop for just a few seconds, to take the time to draw and by doing so, spark a smile on their face as they think of their favorite objects.

Q: What was the most challenging part of your project?

A: Definitely public participation. I was very worried about how my project depended entirely upon other people’s participation. Luckily, thanks to constant updating and editing, I managed to attract a lot of people and got tons of drawings from these boxes.

Q: What is your main goal in this project?

A: What I considered the most successful were the amount of participation the project received, and, judging from the drawings, how serious the public took my project. Within the short period of one week, I received in total more than 400 drawings. It was a delightful surprise for me that the project inspired so many people to pick up the pen and draw. What’s more remarkable, there was no hate speech or vulgar language, one suspicious-on-life piece and only one sexual joke was found. I considered it successful because it managed to make people think about smallest happiness in a very serious and genuine way.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Comments ()