For the Love of Film: Green Room’s “The Flick”

Ross Kilpatrick ’24E reviews Green Room’s “The Flick,” a play he describes as “a love letter to film.” Written by Annie Baker, the play won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2014.

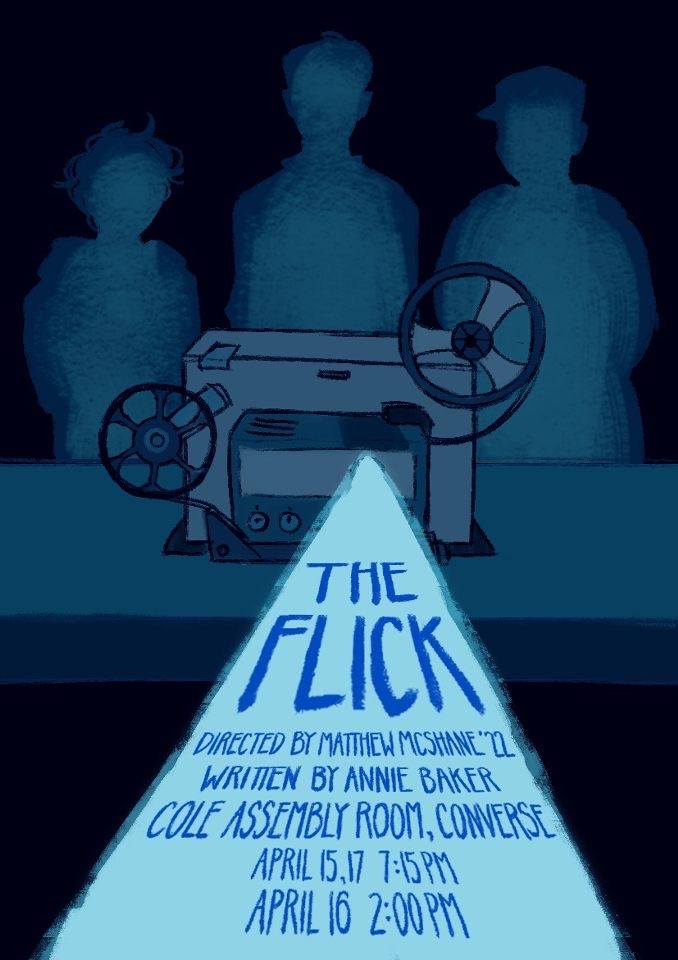

Between 7 and 10 p.m. on April 17, a crowd of about 20 students and I gathered in Cole Assembly Room to watch “The Flick,” capping off a weekend of performances of the show. “The Flick,” which was written by Annie Baker in 2013 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 2014, has now been directed by Matthew McShane ’22 for the Amherst College Green Room. It is above all else a play about movies: all the action happens in the titular theater — which, mostly through the incompetence of its owner, is one of the last of its kind to screen movies with real celluloid film — amidst a muddled slope of chairs, popcorn, and trash cans.

The play opens with new hire Avery (Miles Garcia ’25) being guided by the older Sam (Dylan Schor ’25) while they sweep up spilled popcorn after the end of a film. The play is filled with scenes like this: long sequences of sweeping and silence, allowing the audience to take part in the daily mundanities of minimum wage work — the awkward and uncomfortable — and the mismatched people making the best of it. There’s also the projectionist, Rose (Lee Folpe ’23), and the core of the play is the bonds these workers form between movie screenings.

Their friendships are shallow and insubstantial, but also funny and, at times, moving and real. “The Flick” is a play about a very specific time and place — circa 2013 in a dying theater. The play takes snapshots of these people’s lives, single frames, and transforms them into something worth watching.

And it better be worth something, because “The Flick” is a titanic three hours long, the audience only granted a brief reprieve during a 10-minute intermission. But despite the length, the production is both breezy and stunning. The performances from each of the actors sell the awkward, stumbling friction of normal conversation. And the space itself feels appropriate: the Converse Red Room blurs the division between stage and audience. I could practically touch the actors, and at times it felt less like I was an audience member, and more like I was a theater goer who had overstayed a screening. All of this is to say, it’s a wonderful production of a wonderful play.

In some ways, the play is an odd choice for 2022. Post-Covid, theaters, an already dying breed, are dying even faster. And “The Flick” is noticeably of its time, which both marks and endears it. Recent cinema has been dominated by superhero movies, but the Marvel Cinematic Universe and its imitators really only took off around 2015-16, so Avery’s pronouncements about cinema — that nothing good has come out of America in the last 10 years — and his obsession with preserving the fast disappearing art of real, celluloid film projection, now feel like sadly accurate predictions instead of timely observations. Projection is dead, long live the MCU.

None of this to criticize the play. It’s a love letter to film, to everything the medium can accomplish, and everything it can’t. It’s a love letter to the people who like film, too. It’s a play about work and love and misery. Toward the end of the play, Avery says that “film is a series of photographs, separated by split seconds of darkness.” “The Flick” itself takes place in those moments of darkness, between the bright lights of the cinema, when people come in to clean up our messes — popcorn and soda and whatever else we’ve left behind.

Comments ()