Four Years in Reviews: Final Thoughts

So here it is, huh? Almost four long years ago I donned my writer’s cap for The Student for the first time. Now that I’m graduating, I’ve been feeling a little nostalgic lately. I decided to look back on some of my first reviews for The Student. I was prepared to be embarrassed by the poor quality of the writing, the less verbose vocabulary and the messily structured sentences. But, essentially, I kind of assumed they’d read like worse versions of my reviews today. I was quite wrong. I was prepared for my view of particular films and particular types of films to change, but what I see looking back is that how I evaluate films is dissimilar now from four years ago. What a film is to me has changed to me. And it hasn’t done so by happenstance, but as a result of academic experiences I initially assumed had nothing to do with film.

Some of my earliest reviews of 2010 films are markedly different from the reviews I would write of the same films today. When I wrote on “Blue Valentine,” for instance, I emphasized the quality of the storytelling for its ability to starkly detail an unglamorous view of a struggling relationship and above all for not stacking the deck in favor of either of the central characters. At the time, I felt, any movie which did not do so was simply the product of a filmmaker who lacked skill. Markedly absent from this review was gender. Most films, especially romances, and to some extent even “Blue Valentine,” give the female figure the short shaft, essaying her as a conniving, shrewd stereotype rather than a full-fledged human being. This isn’t only a mark of bad storytelling, but the result of unconscious and conscious norms which construct social definitions of women as manipulative and overly-emotional.

Moving away from this, as “Blue Valentine” is somewhat successful at, is a mark of subversion of social norms. With “True Grit,” another of my earliest, I was initially interested in how unaffected and traditional the film was in comparison to some of the Coen Brothers’ quirkier attempts at genre subversion. Now, the deconstructionist in me can’t help but see how Jeff Bridges’ bumbling lawman doesn’t merely complicate a character, but challenges a depiction central to not only the Western genre but to America’s classicist conceptions of the strong white male lawperson who upholds justice in a fashion nothing short of capable. Meanwhile, the film’s central child character, bruised and battered, reveals much about the falsity of the collective U.S. memory of the American West as a gentler, more compassionate time.

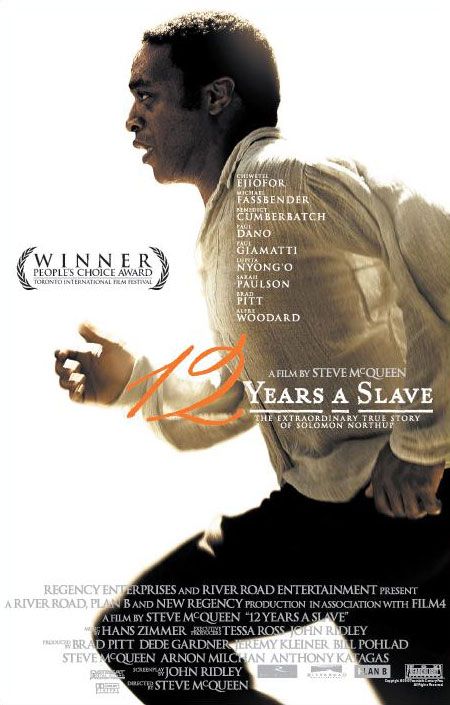

In comparison, my more recent reviews were consciously written with an eye for the film’s context and how this speaks not only to a literary construction of strong characterization, but to a morality and the reproduction or challenging of social norms. “12 Years a Slave” is a masterpiece of filmmaking, carefully measured yet searing with passion and by turns quietly and thunderously anguished. But it is all the greater for the context in which it arrives, being the fullest and most telling film to deal with American slavery yet made in a time still marked by its own newer forms of racism, but forms with significant linkages to the time “12 Years a Slave” depicts. Likewise, I wanted to write a review of the haunting “Zero Dark Thirty” not because I felt it was well made (which it certainly is), but because I felt everyone was misconstruing the film’s morality. Because the film implied U.S.-sanctioned torture of hostages could have led to information about Osama Bin Laden’s whereabouts, the immediate reaction was to assume the film endorsed terrorism. However, in doing so, the public failed to question whether the film endorsed the hunt for Bin Laden in the first place. The depiction of the main character, someone who is rarely shown outside of her office or in the field, sees her as someone who devotes the better part of a decade to the hunting and killing of another person, no matter how horrible he may be. She has no outside life, no friends, no home; she’s all alone, and when the film’s finale occurs, it’s quiet, reserved, almost a non-event. Upon witnessing a decade’s work lying in front of her in a black bag, she can only cry. That doesn’t sound like unrestrained support for the war on terror, or the hunt for Bin Laden, to me. By acknowledging that torture may have played a role, the film is able to tackle the more difficult question, not of whether torture can lead to useful evidence, but whether torture is worth the useful evidence which may come from it.

Both these films were powerful and left an impression on me, but not purely because of their mastery of technique. Their importance to the society which birthed them added to their effect. When I entered Amherst, I was firmly against the view that anything outside of the film’s technique could or should matter in a judgment of its quality. Filmmaking was a skill, plain and simple, and could be objectively judged. Now, thanks in large part to my sociology career here, I have come to see films, as with all art, for what they are: not as objective markers of quality but as reflections of the societies which breed them, societies which judge quality and worth subjectively and which dictate the morality of all films, even subtlety and even for films with no ostensible political axe to grind. In this light, films are subjective, and can and should be judged subjectively. Because films are meant to speak to audiences and are made by individuals (and corporations) which are themselves products of that society, they inhabit the frameworks of knowledge which govern the societies. They are products of subjective societies, and pretending that this isn’t the case and that the things we take to be objective markers of quality aren’t subjectively defined based on the values of our society is not only wrong, it’s deeply problematic. Denying this reality doesn’t diminish its truth, it merely hides it.

The stigma around acknowledging the subjectivity of the supposedly objective qualities we value in film is perhaps most apparent with a film I avoided viewing because I was unable to resolve the moral tensions within. A cartoonish revenge fantasy depicting a black ex-slaves freedom and subsequent murdering of many a white person in the Old South, “Django Unchained” presents a fantasy version of slavery. Yet, within, it subverts a key stereotype that it initially seems to subscribe to: that a white man must rescue and train the slave for his eventual independence. Through subtle but key dialogue choices, however, the film questions the sympathetic-liberal-white-male-savior-dentist-turned-bounty-hunter stereotype (ok maybe Tarantino added that last part), ultimately having no choice but to relegate him to the same fate as the whites Django kills: a swift death. Ultimately he uses Django as his slave for his own purposes, a stinging commentary on the white savior myth. He is complicit in his own “flesh for cash business”, as he refers to it, and the market-inequality which has human worth conveyed in purely monetary, dehumanizing terms. And in Tarantino’s world, he cannot continue living for the same reason the film’s villainous slave master Calvin Candie can’t. On one hand, it allows, perhaps for the first time in mainstream film history, a black male to seek revenge on whites, something which historically was the privy of male freedom fighters and their much argued-over killing utensils. On the other, it maintains masculine and hegemonic notions of equating justice with active violence. In other words, “Django” is a mass of contradictions, endlessly fascinating and perhaps irreconcilable. 18 months ago, I avoided it because of this; I saw it’s inconsistency as a flaw. Now I see it for what it is: a product of an inconsistent society which has progressive forward-thinking and conservative inequality often sitting side-by-side (or even inhabiting the same body). It’s a film worth endlessly debating and something which refuses to be easily defined. “Django’s” morality may not be easily resolved, but it all but begs to be addressed. It’s an innately political film because it exists in a society where race is a political issue, and rather than foregoing these issues for a paint-by-numbers analysis of the film’s technical merits, we should consider its characters, narrative, and morality in all their contradictions and complications. Works of art shouldn’t be “beyond” political or social judgment, at least insofar as discussion goes — the two are fundamentally intertwined and should be treated as such.

Initially, I saw writing about film as a fun aside, something I could write about and not be pressured with the tensions of academic deadlines, and above all, the weight of the subject matter. In doing so, however, I was presupposing a certain belief about the worth of various forms of writing, various subjects. Sociology and social inequality, unlike film, were valid subjects of “weight”, despite the fact that films were products of societies and exhibited in multi-faceted ways the same tension I would and do write about academically. It took me a while to develop the courage to utilize film commentary as an outlet for writing about social justice and social relations, but I’m glad I did. By learning about film we learn about people. And I’ve enjoyed using The Student these four years as an outlet to learn about people, even if it took me a while to realize it.

Comments ()