Fresh Faculty: Ohan Breiding

Ohan Breiding is the college’s artist-in-residence for the 2022-2023 academic year. They work with photography, video, installation, and collaboration. They hold a B.A. from Scripps College and a M.F.A from California Institute of the Arts.

Q: What is your background?

A: I grew up in a small village in Switzerland, and, during that time, I played professional hockey. I dropped out of high school, and by then I was already making art; I would go and paint in the woods. I was really into painting and being outdoors and then I realized that to be a serious artist, I should really also study art history. So I ended up going to Scripps College in Southern California, and I double majored in art history and studio art. While I was there, I studied abroad at the Glasgow School of Art. I was drawing, painting, and printmaking, and then when photography was introduced to me, I realized that was the medium I wanted to work in. I met this photographer and I was like, ‘Oh, this is so exciting that I can just take photographs of everything I was trying to draw and paint but wasn’t able to do realistically.’ And then I really started to focus on photography much more.

Q: Tell me about your art.

A: I work primarily in photography, video, installation, and collaboration. And I often work around themes of the landscape and the landscape-as-witness to think through historical events, oftentimes in relation to violence or trauma, in order to rectify and/or give voice to those who have been made invisible. For the last few years, I’ve been working on a project that takes the story of a family member who survived a tsunami and then thinks through the ocean as a space for recovery and as a space for thinking through immigration, migration, plastic pollution, and connecting science to politics.

Nature is really important to me. I love the Alps. I also love the ocean, especially since a lot of my work is about the ocean now. I just was in Los Angeles last week, and I’m a part of a queer surf collective. So surfing is really important to me too.

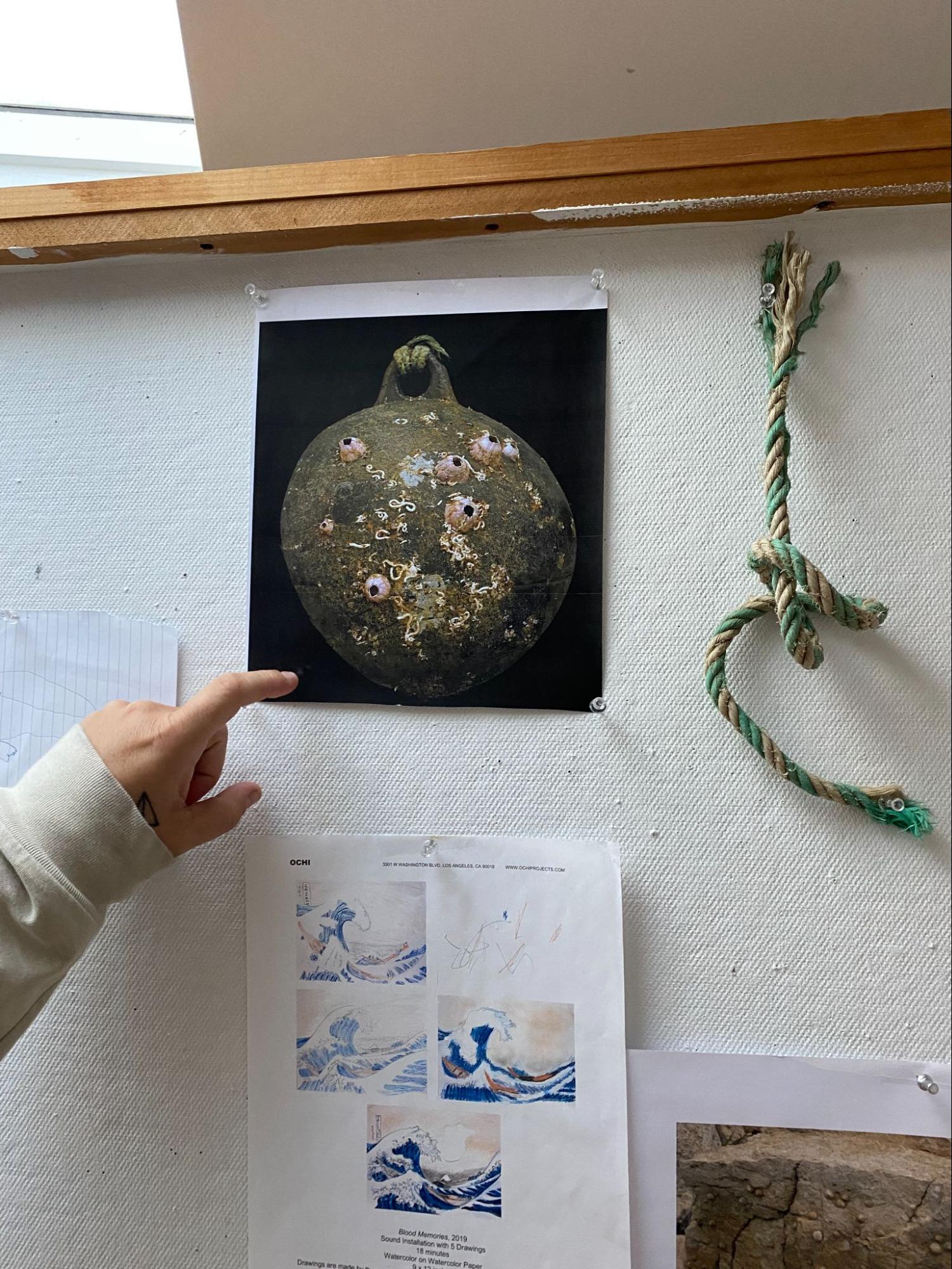

So right now, for example, I just had seven of these octopus traps from Portugal sent to me. I’m really obsessed with octopi. I love them and think they’re just magical and a highly intelligent, weird species. Just last summer, I was doing a residency in Portugal and I was filming these octopus fishermen coming home, and when I saw these [octopus traps] I just thought they were really beautiful objects and strange. I was really drawn to them and interested in thinking of how to animate them and talk about this space that carried these octopi. And there’s all this life that has grown on them, so I was really interested in thinking about how these traps work and using them as sculptural components or components that I might end up photographing or filming or drawing. So right now I’m sitting with these seven plastic, strange-looking objects and thinking about the lives that they kept, that they were holding. Also about their contradictions as both a house or a place that probably felt very safe for these animals, and then ended up being the last place where they were physically alive.

Q: How much does science inform your art?

A: [My work is] usually not this science-heavy, just for this project. Before I got the job at Williams College, I was reading this article from Science magazine. And there’s this person, his name is Jim Carlton, he’s a marine biologist, and he actually taught at Williams for many, many years. He’s retired since, but he’s the person who was researching marine debris [published in Science magazine]. So, an example of marine debris is buoys from Japan that traveled from the 2011 Tsunami all the way across the Pacific Ocean and ended up on the coast of California, Oregon, and Washington. His job is to research what are called “rafters” or “hitchhikers,” which are animals that had been attached to these plastic objects and were able to survive up to 11 years now. And so I’m really interested in working with him to think through connections between different species — thinking not just about humans, but also animals.

And, unfortunately, the reason this is happening is because of the abundance of plastic — [with] wood, the wood would disintegrate after a few years or so, but because we have so much plastic these species are arriving at different coasts [where] they’re considered invasive species. I’m really interested in the language that’s being used to talk about them, and so this is part of thinking through another aspect of the Pacific Ocean in loving connection to my family member who survived the tsunami.

Q: What brought you to Amherst?

A: I just was really interested in doing a one-year residency. I thought it was very exciting to have time and space to focus on making an exhibition and to be able to teach students content that is exactly overlapping with my research and art practice, leading up to this exhibition.

I think [once] I knew I wanted to be a full-time professor, I was really drawn to liberal arts colleges where I just felt like I [could] get to know the students much more — it’s much more intimate. And it gives me the experience [where I can] still be a full-time artist, but also be a full-time professor at the same time. I think there’s something about the intimacy and having access to both feeling really close with the students and the professors, and everyone involved in an institution, but also knowing that I can remove myself and really focus on my art practice separately from that.

Q: What do your days look like?

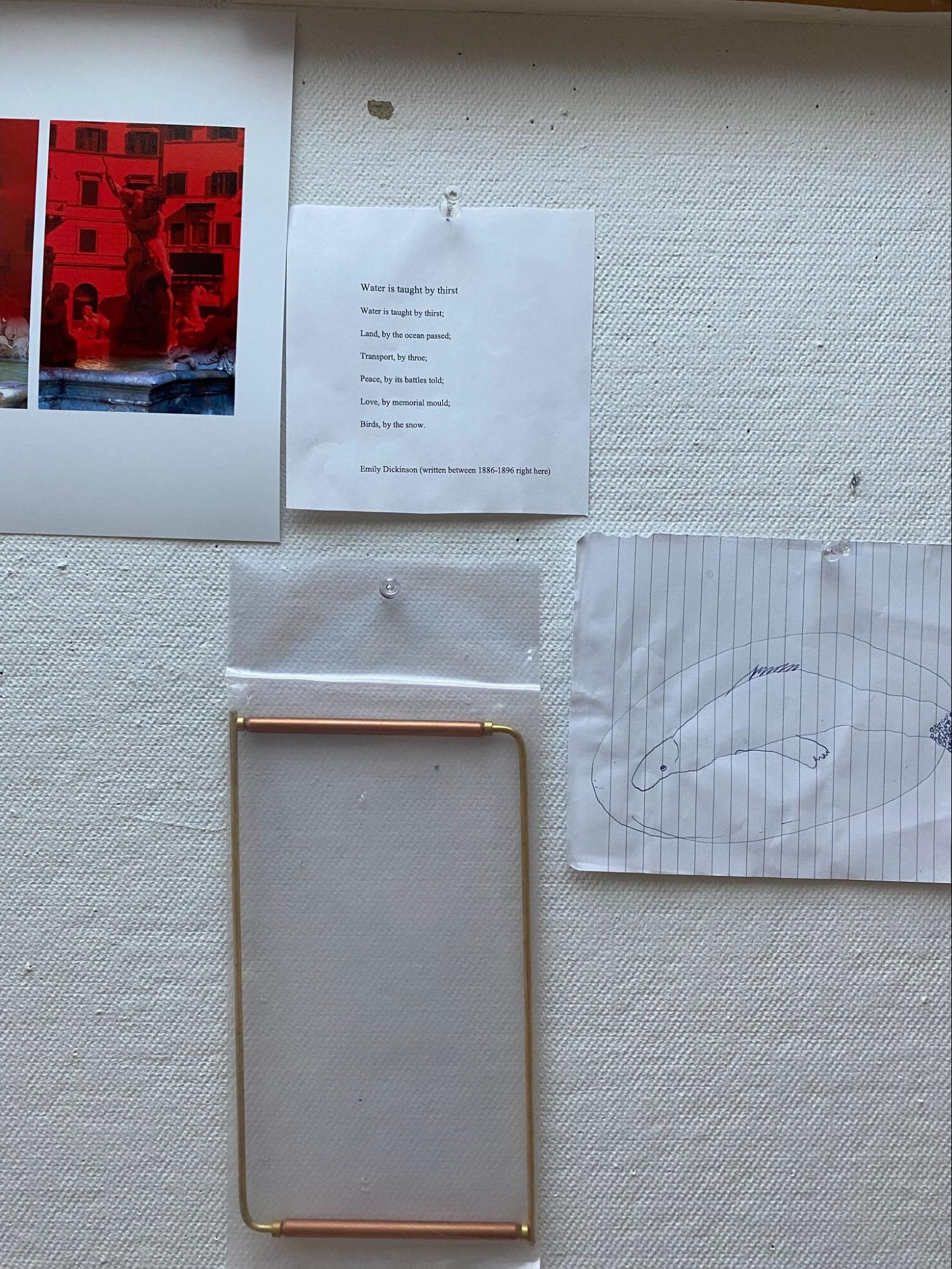

A: I basically spend hours, many, many hours — like a full-time job — working on projects and on research, doing reading and studio visits, spending a lot of time thinking through what this exhibition is going to look like, along with preparing for and then teaching the class that happens on Wednesday afternoon.

I usually walk: Walking as a practice is really important to me, and getting to know this landscape. Walking near water or being in water is really important. And then reading and, like, the research component is a really big attribute. And then I’m physically making things.

I also, right now, have a studio on Governors Island in New York City, so I also spend my time going there and being surrounded by saltwater. And in that studio, I’m with other artists so there’s more room for exchange and studio visits. A lot of my practice involves just having dialogue with artists and non-artists, scientists and poets, and people that I just like to have conversations with. Also just being able to see other art or feel inspired by going to exhibitions or being around other artists, I think, is really inspiring. And so that happens in New York City.

Q: Tell me about your class, “Water as Leitmotif: Queer Kinship and Collaborative Acts of Performance for the Camera.”

A: The class is [about] looking at water as a form of poetics, politics, and material. And the theme of water as medium goes throughout the entire class. For today, [students] read this amazing text called “Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons From Marine Mammals.” Last week, they read Maggie Nelson's “Bluets.” For next week, they’re reading Adrienne Rich’s “Diving Into the Wreck.” We look at texts that are written by women and queer and trans and POC writers and/or artists, that all use water in their own practices as throughlines or leitmotifs. And then, according to the texts, [the students] also do different kinds of experiments and assignments that happen every week, along with rituals.

So, just for example, today we all were given a plastic bag, and we filled the bag with our air and made a knot into it, and then passed our breaths to each other’s hands — we were all holding each other’s breaths. So [the rituals] are kind of like strange poetic experiments that hopefully will make students feel this notion of embodiment or thinking through what it means to be a body within a collective formation, to think about our bodies as like, ‘Hey, you’re bags of water.’ We’re all made out of water, and all of our water originated from the same ocean network, but we are very different people.

For next week, they were given emergency blankets. So each student was given an emergency blanket, and then dowsers. They’re these tools that are made out of brass, and if you hold them, they're supposed to show you where water is located. And so they, collectively in groups of four or five, are making a performance piece where they need to use the emergency blankets and these dowsers. And those are the only guidelines.

[The classwork is] more like giving them different means to experiment that will then lead them to figure out what they really want to do in their own practice. So trying to think through structures of what it means to be an artist, and how a lot of times experimenting or making things that end up failing is really important, and then trying something new again. The critique is a really big format that we use: ‘What’s at stake in the artwork? How do the formal throughlines connect through the format? What could be improved?’ We’re thinking through both analytic and literary [literacy], but also visual literacy in order to help students think about how they can write and talk about their own artwork.

I hope [my students] find a sense of joy and excitement, and also how to learn through feeling and embodiment rather than just thinking. And that they challenge their own [photography] practices or even beyond photography, thinking about collaboration as a medium in itself. And maybe being able to see their daily lives in a different way where water becomes more apparent, and then link the inside of the body to the outside of their body to other people’s bodies, or their bodies to the landscapes that hold us. I also hope that they get a sense of gaining new friends or creating friendships through these experiments and rituals.

Q: What are your goals for this year?

A: My goals are to hopefully teach a class that students really appreciate and enjoy. And then to create this exhibition that I feel very proud of, and that I hope people will come and spend time with and be able to also appreciate. And, you know, hopefully for my students to also see this overlap between what they’re learning in my class versus my own research that I’m doing, and how that’s been translated into the visual arts.

For my next semester, I’m really excited to be collaborating with my students, and include students in the making of maybe one of the pieces that will be included in the exhibition, but also to be collaborating with writers, invite writers to write about the artwork, and create a catalog or some form of an object that will live in the world beyond the exhibition dates.

I’m also really excited to continue taking walks and getting to know the different bodies of water. There’s so much water in so many different rivers here, and lakes. So I think [something I want to do is] just exploring this landscape.

Q: What are your favorite books?

A: Anne Carson is a writer I love; I also love Eve Sedgwick. I love this book, “From Trinity to Trinity,” by Kyoko Hayashi, Christina Sharpe’s “In the Wake: On Blackness and Being,” “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” by Ursula K. Le Guin, and “Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology” by Astrida Neimanis. These four [books] are really important to me.

Comments ()