“I’m Still Here” Review: A Victory For Democracy

Following the Oscars, Managing Arts & Living Editor Mila Massaki Gomes ’27 covers the significance of “I’m Still Here” winning Best International Movie, marking the country ’s first victory in the category.

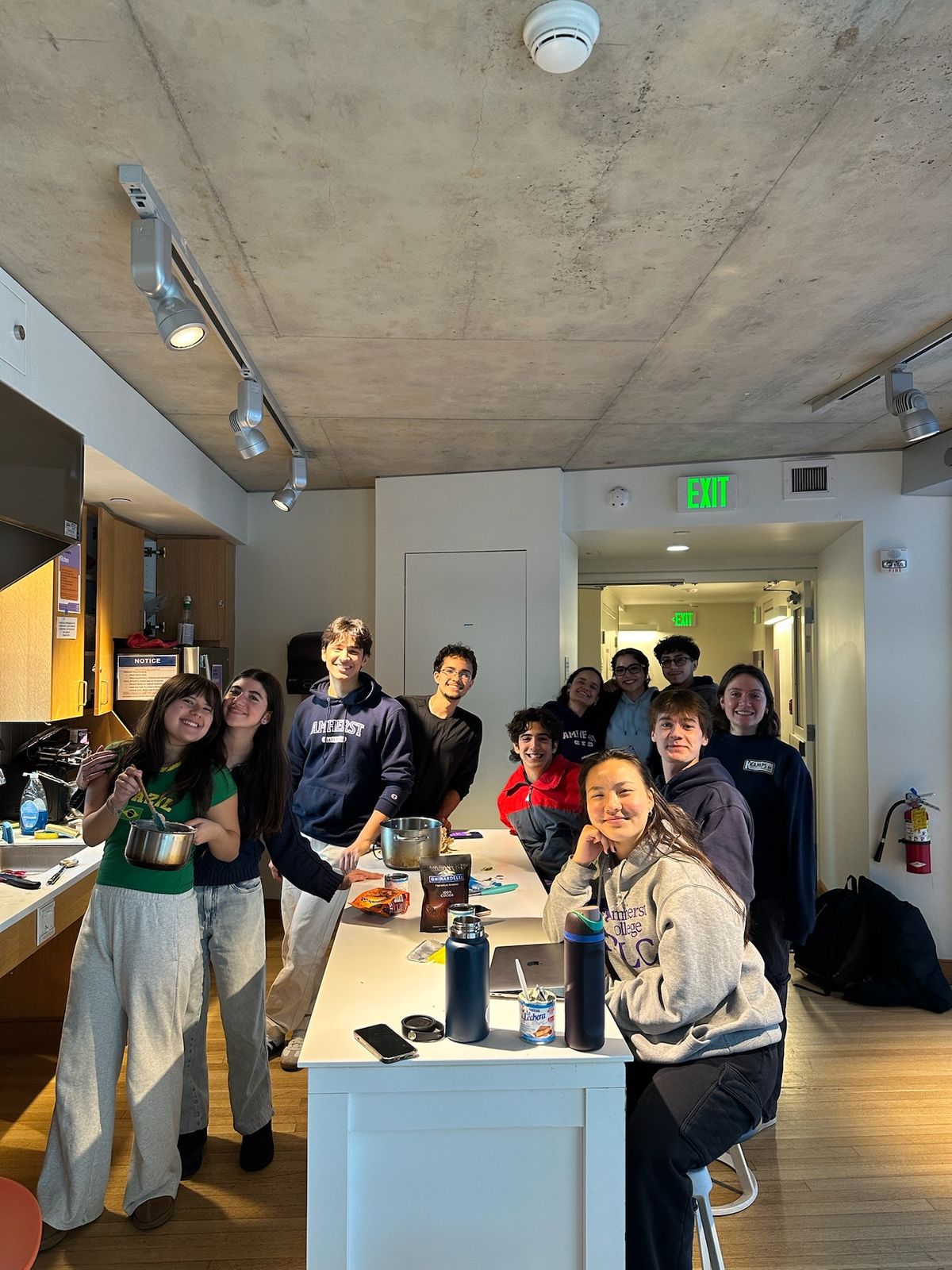

I think the hearts of almost all Brazilians were beating as one in the moments before the Oscars for Best International Movie, Best Actress, and Best Motion Picture were announced — with each category, a chance that our movie, “I’m Still Here” (dir. Walter Salles), would make history as the first Brazilian production to bring an Oscar home. That was the case for those of us in the Brazilian Student Association, who sat at the edge of our seats on a couch in the Greenways’ Nicklas Hall, hands sweaty and clasped tight. Fernanda Torres, who plays Eunice Paiva in the movie, had the chance to not only bring home Brazil’s first Oscar in the Best International Feature category but also to avenge her mother, Fernanda Montenegro. Montenegro is the only other Brazilian actress to be nominated for the award, having been recognized in 1999 for her part as Dora in “Central Station,” also directed by Salles.

When Penelope Cruz announced that “I’m Still Here” had won Best International Movie, the first of the three awards it was in the running for, we couldn’t help but jump up from our seats and scream in joy. In an instant, we were hugging each other and sharing tears of happiness and relief. History was being made, and everywhere in Brazil, people stopped their celebrations of Carnaval, one of the biggest holidays in the country, to commemorate the victory and recognition of our national cinema at the Oscars.

As fate would have it, “I’m Still Here” did not win in any other categories for which it ran. Torres never got to avenge her mother, and the miracle of an international movie winning Best Picture was a dream left behind with “Parasite” and its victory in 2020. And while we mourned what could’ve been a sweeping victory and the end of our distrust in the academy, we had to remind ourselves, as Eunice had to smile despite the pain

“I’m Still Here” tells the real-life story of Eunice Facciola Paiva (Fernanda Torres), Brazilian lawyer, activist for Indigenous rights, and challenger to the military dictatorship that took over the country from 1964-1985. But the movie opens on the beach in Rio de Janeiro, 1971, before Eunice was any of the above-mentioned things; she swims in the ocean, her husband talks architectural business with his coworker, and her children enjoy the summer morning in the sand. At the end of the day, soaked in salty water and sunlight, the family reunites in their big house, and there is no doubt that this is the story of a happy family in the country of soccer and good music. That is, until the oldest daughter, Vera (Valentina Herszage), joins them. Out of breath and desperate, Vera explains that the military had just stopped her and her friends for no reason other than that the cops were looking for supposed “enemies of the state” and all cars on the street could hold in them a person worth investigating. The TV in the living room is playing the news: another foreign ambassador has been taken hostage by the corrupt military — a recurring event as the military sought to exchange these ambassadors for Brazilian political criminals detained in Europe. The beach day, once warm, ends in a cold realization for the audience that this is not the same Brazil we love and live in today.

While the life of the family continues — their house always full of music, guests, and children playing sports and games — in the background of the scenes, we are served reminders that while the family is saturated in happiness and light, the political reality of the country is not so bright: book owners, musicians, and left-wing families are seeking exile, war tanks are parading the streets, and when the children aren’t listening, the adults take turns speculating about the next worst thing to come.

It is just another normal day when the life of the Paiva family turns completely upside down. Eunice and her husband, Rubens (Selton Mello), are playing backgammon in his office, lunch is being made, the children are all playing outside, and then a group of men knock on the door. They are looking for Rubens, saying he knows some important information and take him to what they call “routine questioning.” These men are not clad in uniform, and they have no badges or permits, but they enter the Paiva home, take away the father of the family, lock all the doors and windows of the house, and set forth the rule: “from now on, no one goes in or out.”

Eunice and her second-oldest daughter, Eliana (Luiza Kosovski), are also taken to be questioned at the military base. Tortured screams can be heard in the background, and both women are questioned endlessly about things and people that they simply do not know, their request for water unanswered, and their questions about the whereabouts of Rubens met with silence. Eunice has nothing but her dirty prison cell. That was the reality of the dictatorship: not a house filled with love and light, but a prison replete with screams, torture, and pain. While Eunice and Eliana are released after a few days, Rubens never returns. All the light and warmth are gone with Rubens, and from that moment on, no more music plays in “I’m Still Here.’’

There is no death certificate, no document to prove the police took Rubens. Everyone expects Eunice to be desperate. She lost not only her husband but everything they had built so far: their savings, the plans for their dream family home, and their growing love for each other. International magazines interview the family; they want a picture of her and her kids, sad, indignant, and desolate at the destruction brought upon them. But Eunice asks them why: why do you want a sad picture of us? She holds her children tight and tells them, “We will smile.”

The atrocities of the military dictatorship did not destroy Eunice and her family; they were still there. In the years that followed, Eunice went back to college and became licensed as a lawyer. She became a championed activist for the protection of Indigenous land and people, as well as one of the main advocates for the human rights of victims of political repression. It was, in part, because of all of her efforts that many families with members who were killed by the dictatorship were finally able to receive the death certificates of their loved ones.

“It’s weird to be happy about a death certificate,” Eunice says. It is almost as weird to be as happy as many Brazilians were after not winning the awards we thought we deserved. But death and loss were not and are not the real reason why we smile. We smile because even in our defeat, we have already won. We smile because the mere fact that “I’m Still Here” exists is a testimony to having won the fight for democracy. We smile because we can still look at the past and tell our history as it is, truthfully. We smile because we are still free enough to speak up and call for justice — justice for people like Rubens, who never got to enjoy the rest of their lives while their torturers still get to roam freely on the streets today. We smile because in a parallel universe, movies like “I’m Still Here” never got to exist, but in ours, it does.

It is weird to celebrate after losing so much, but we must because our liberty is not a given. Our liberty is like the Paiva house, just as susceptible to the end of light and color as it was. Our freedom to practice art, music, theatre, and even journalism is a battle we won but a victory we must still fight for every day. “I’m Still Here” may not have won the Oscar for Movie of the Year, but it is, at its core, a victory for democracy and a reminder that we must never stop smiling so long as we are fighting for what is right.

Comments ()