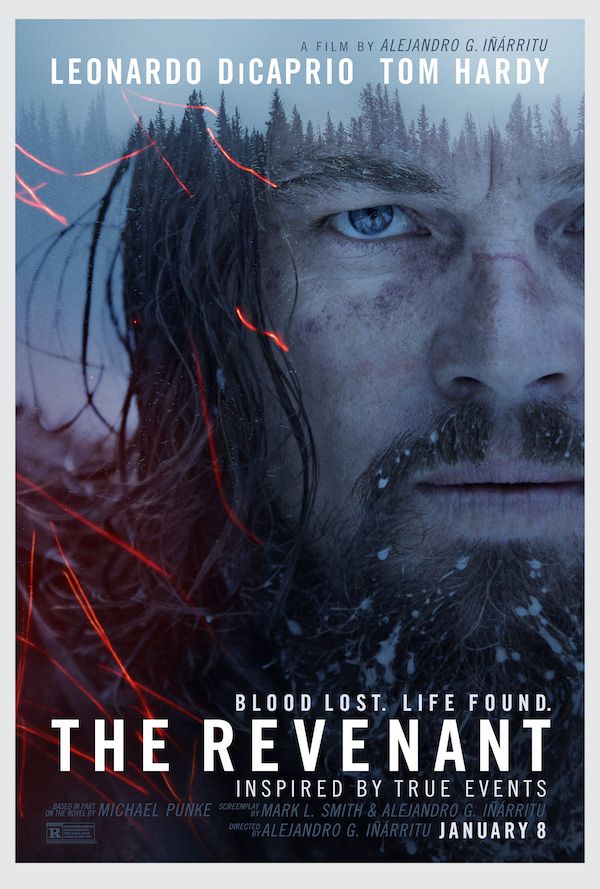

Leonardo DiCaprio Depicts Tremendous Suffering in “The Revenant”

To find an Iñárritu film during the cinematic famine that comes around every January is to find an oasis in an oft-traversed desert. The Mexican director has efficiently carved a hobbit hole in the mainstream moviegoer’s consciousness, and “The Revenant” is an unabashedly loud stroke of the chisel that reminds everyone that he is here to stay.

The story very loosely follows the real-life account of fur trader Hugh Glass who, against all historical odds, finds love in a Native American tribe. He bears a child, but soon the guns and germs and steel claim the lives of the tribe. He and his son survive but in order to eke out a living, the two join a trapping expedition that meets an explosively violent end. During the escape, Glass is mauled by a bear, and his fellow survivors find him at the brink of death. The leader of the expedition, unwilling to let yet another man perish under his command, offers to pay people to stay behind with Glass and his son. One of those volunteers, named Fitzgerald, judges that Glass is a hopeless clause and attempts to smother him after the rest of the expedition leaves. Glass’s son tries to stop him, but Fitzgerald overpowers the boy and murders him. Fitzgerald proceeds to trick his fellow volunteer into believing the Native Americans are coming for revenge and leaves Glass to die. By some cruel miracle, Glass survives and props his mangled body up for a long, bitter trek across the frozen heart of America in search of justice.

With “The Revenant,” Iñárritu’s trademark visual style makes a resplendent return to the screen. At almost every opportunity, the director inserts long, stirring shots of the landscape whose snowy curves, peaks and valleys continually dwarf the cast. These shots are perhaps too long; near the end, when the disparate threads of the plot begin to converge, the shots only serve to disrupt the act’s pacing. These long shots are accompanied by equally long silences, occasionally interrupted by the winter winds and DiCaprio’s grunts. The frequent use of silence directs the viewer’s attention to the action, which in turn provides the bulk of the film’s intrigue. The camera lingers just a bit too long for the audience’s comfort at the explosions, taking care to closely document the fleshy debris. The much-touted “bear sequence” is not even the most brutal scene in the movie. Above all else, the movie’s momentum never fizzles out; the snow just gets redder and redder.

Thankfully, the subtext of the film explains these stylistic decisions at every turn of the plot. “The Revenant” is an extended visual metaphor for the violent and extractive relationship between Native America and the colonists. DiCaprio serves as the latter’s maimed conscience and hope for reconciliation. This rather unsubtle thematic spine is what allows this film to transcend beyond torture porn, marketing notwithstanding. At no point in the story does the movie forget this, and it relishes every bout of violence inflicted on poor Leo, whose sole source of motivation throughout the infamously grueling filming process probably was the prospect of receiving an Oscar and possibly strangling Iñárritu at the ceremony.

Unfortunately, if Leo was in it for the golden statuette, he probably should have declined this role. His role is physically demanding to be sure, but not one that requires any significant interpretation on the part of the actor. Grunting and mumbling comprise the bulk of DiCaprio’s lines, and in the rare occasions in which Hugh Glass has to emote, DiCaprio comes off as lost at best and insincere at worst. More importantly, Hugh Glass, along with the rest of the entire cast, is not very interesting. Perhaps it was Iñárritu’s iron will to prioritize the main message above all other elements in the production (excluding the gorgeous visuals), but the characterization is uniformly weak in this movie. The characters are little more than symbols coated with coarse flesh and filled with copious amounts of blood, and while the suffering they undergo is visually horrifying, it alone is not sufficient to have the audience care for them as characters. The only symbol that approaches any semblance of complex humanity is Fitzgerald, and the movie is quick to reduce him into a fleeing villain for our wheezing and heaving protagonist.

Overall, “The Revenant” is a film whose flaws and appeal are perfectly summarized by the director’s name. It is the predictable, natural and overall satisfying next step of Iñárritu’s evolution as a filmmaker. Its shoddy characterization and occasionally overindulgent scene-chewing limits it to being a missing link for his magnum opus. However, the film’s deficiencies do not detract from the fact that it is a sumptuously directed and royally financed work with an important message whose price of admission is worth paying for the sake of the spectacle alone.

Comments ()