Mammoth Memories: The Beginning of Baseball

Join Managing Sports Editor Alex Noga ’23 as we uncover some of the fascinating details about the college's storied past in the new sports column "Mammoth Memories." Our first stop: the very first organized baseball game ever played.

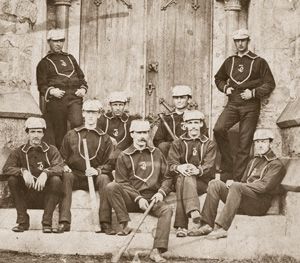

Amherst College boasts the oldest collegiate baseball program in the world. Amherst is widely recognized for playing — and winning — the first ever intercollegiate baseball game against perennial rival Williams College. The game took place in 1859 — 44 years before the first World Series — the same year that Oregon was admitted as the 33rd U.S. state and two years prior to the start of the Civil War.

The contest was originally proposed by Williams and included a subsequent chess match between the two schools, with the objective of conducting a “trial of mind as well as muscle.” Williams administrators insisted that the schools play at a neutral location, which was determined to be Pittsfield, Mass., a simple 20-mile journey for Williams but a 90-mile trek for Amherst. Because neither school had an organized club for the sport at the time, the two teams were chosen by a ballot that consisted of the students at large. But that didn’t necessarily mean that no one had any experience in the sport: the Amherst junior and sophomore classes had played a game against each other the previous year.

Baseball in the 19th Century

There were two forms of rules that governed baseball at the time: Massachusetts rules and New York rules. New York rules more closely resemble the modern game, but Massachusetts rules were better established at the time and were chosen for the contest.

Under Massachusetts rules, the two teams used a square playing field rather than the current baseball diamond. Bases — four-feet-tall wooden stakes that emerged from the ground — were placed 60 feet apart from each other. The “striker,” or batter, stood halfway between first base and home plate (referred to then as “home base”), while the “thrower,” or pitcher, stood in the center of the field.

Like cricket, all batted balls were considered in play. There were no balls or called strikes when pitching — strikes were only called if a batter swung at a pitch and missed. If a striker repeatedly refused not to swing at good pitches in an attempt to delay the game, however, the umpire would first give a warning, and then start calling strikes if the batter continued to let good pitches go. Like the classic modern game of “running bases,” pegging was allowed, meaning an out could be recorded if a fielder hit a runner with the ball.

Each inning lasted only until one out was made, so the game was played until a specific number of “tallies,” or runs, was recorded. Amherst and Williams decided to play to 65 tallies, with rosters composed of 13 players each. Each team provided its own ball, each with slight differences, which was to be used when its respective team was in the field.

“They had never seen so fine amateur playing”

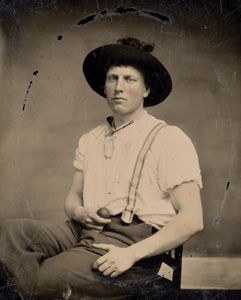

The game began at 11:30 a.m. on July 1, 1859. Amherst started the game as well as any team could, as catcher and captain J.F. Claflin ’59 led off with a home run to put Amherst on the board first. Williams pulled ahead in the second inning to take an early 9-2 lead, but Amherst never faltered — scoring 12 times in the fifth inning, they took a 22-20 lead and never looked back. Amherst reached the 65-run mark in the 26th inning, but without a mercy rule the inning continued until an out was recorded, allowing them to pile on 10 total runs in the inning, eight more than the targeted tally. The game ended 73-32 in favor of Amherst (Amherst had actually proposed the run-limit to be 75 tallies, but Williams, perhaps wary of Amherst’s might, did not accept these terms).

Amherst was powered by strong performances from the top of their lineup. The top three batters for Amherst generated 19 runs and only three outs. Claflin never made an out and recorded seven tallies, and, as captain, he directed his players when to run on the basepaths, preventing the erroneous baserunning errors that were common among Williams’ runners. He is said to have led with “perfect, military discipline.” The top three batters for Williams, on the other hand, were responsible for just one run and recorded 14 outs.

Amherst also benefited from a powerful pitching performance delivered by H.D. Hyde ’61, who pitched the entire three-and-a-half-hour contest. He is said to have thrown every ball “at the beck of the catcher, with a precision and strength which was remarkable — more faultless and scientific throwing we have never seen.” A rumor circulated among Williams players that Hyde was a professional blacksmith who was hired specifically for the game, “for nobody but a blacksmith could throw in such a manner.” These claims “afforded great amusement to that player and his comrades.”

“Trial of mind”

The chess match took place the very next day, with each school represented by a team of three players who would jointly make decisions during the match. Before the match began, there was a nearly unanimous consensus that Williams would emerge victorious. Chess was mainly seen as a social activity at Amherst, and the skill of their representatives was largely unknown. In contrast, Williams was led by E.S. Brewster, a 16-year-old prodigy who was widely considered to be a chess genius. Brewster, however, was said to have been the victim of a severe stomach ache the night before the match and was not at the top of his game. It must also be noted, though, that Claflin, who had played a massive role in the previous day’s game and was recovering from a sickness of his own, was a member of the Amherst chess team. He was the only individual to participate in both contests.

During the match, each team was allowed 15 minutes to make their move. After a marathon of a game that took a total of 48 moves and 11 hours, Williams was “obliged to yield to the mathematical discipline of Amherst,” as Amherst achieved an unexpected and brilliant victory, their second in two days.

“A copious display of enthusiasm and rockets”

Word of the baseball team’s victory reached the Amherst campus by telegraph at 11 p.m. on July 1, and excitement quickly spread among the student body.

An article from the Amherst Express writes that students, after learning of the victory, “leaped from their quiet couches, and from their open windows made the welkin ring with the shout, ‘Amherst wins! 71 to 31!’” (The text of the telegram relayed this incorrect score rather than the true final, 73-32.) Students assembled on College Hill in large numbers, and the bells in Johnson Chapel played “its merriest peals.” A bonfire was created at the bottom of the hill, and students celebrated “with a copious display of enthusiasm and rockets.”

News of the subsequent victory in chess did not reach the campus until July 4, but it was met with similar enthusiasm that added on to the preexistent celebrations of Independence Day. A parade of gleeful students made their way to the homes of President Stearns and Dr. Hitchcock, who each delivered speeches to the exuberant crowd. Claflin, who returned to campus later than the other players, was bombarded by a large gathering of students in his room upon his return and ended up giving a speech of his own.

Williams requested a rematch in both contests, but Amherst respectfully declined, claiming that it interrupted college duties for too extensive a period of time. After their dominant showings in both fields, what else was there to prove anyway?

And thus, the rivalry between Amherst and Williams was taken to new heights. Even in the earliest days of the rivalry, however, Amherst won with dignity, stating that “these trials of strength and skill will only serve to increase our mutual good will and friendship” with Williams.

Comments ()