Panel Sheds Light on Refugees in Western Mass.

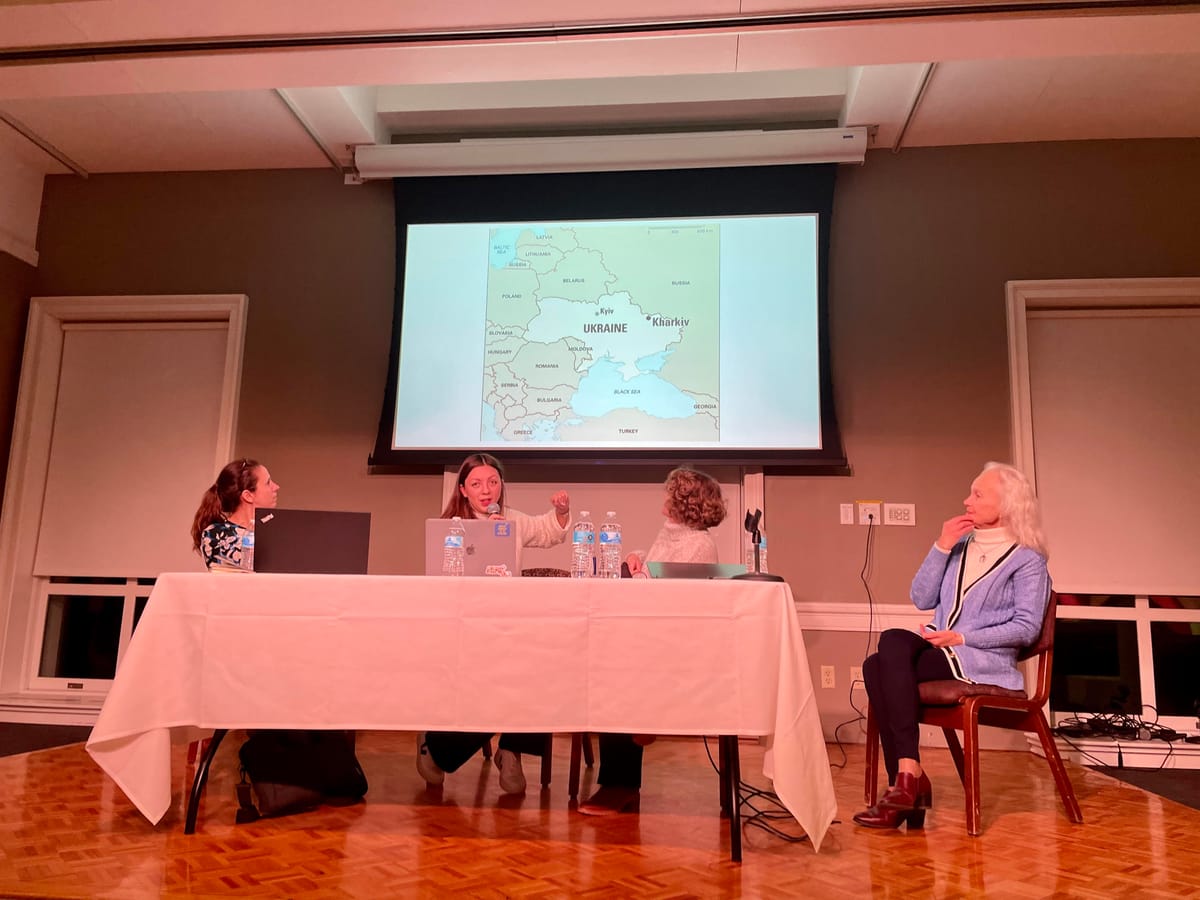

On Feb. 7, the college hosted an event titled "Refugee Settlement in the Pioneer Valley." Panelists spoke on the global refugee crisis and explained the process of resettlement in the Pioneer Valley.

Natalie Rubanska just started a job in Amherst, 5,000 miles away from her hometown of Kharkiv, Ukraine. Even though it’s been a year since her departure, Rubanska still constantly asks herself, “What am I doing here?”

Rubanska spoke on Tuesday, Feb. 7, at an event titled “Refugee Settlement in the Pioneer Valley: A Panel Discussion of Process, Challenges, and Client Experiences,” sponsored by the college’s Center for Religious and Spiritual Life and its Office of Immigration Services.

Rubanska served as a panelist along with Urszula Wolanska-Fettes and Kathryn Buckley-Brawner from Catholic Charities and Sara Bedford from Jewish Family Services of Western Massachusetts (JFS). They defined relevant terms describing displaced persons, gave statistics on the refugee crisis, explained the resettlement process from the international to local level, and offered anecdotes from clients.

The event is particularly pertinent in the context of ongoing global humanitarian crises, including those in Afghanistan and Ukraine, Buckley-Brawner said.

Before 2022, there were 44.7 million displaced persons and 26.6 million refugees globally while as of 2022, the global number increased to 100 million displaced persons and 32.5 million refugees, Fettes said.

Bedford drew from her 17 years of experience to respond to the turmoil caused by the Afghan evacuation in addition to other crises.

The center, which Bedford said had been “shriveled like a raisin” before the current crises, has gone from resettling 60 people in a year to 200 in just four months.

Given the sheer volume of refugees, it can be easy to “forget that each person is an individual with faith, hope, and aspirations,” Bedford said.

Rubanska, in her public speaking debut, relayed her first-hand refugee experience to close the panel.

When the Russian army invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Rubanska fled her hometown of Kharkiv with her 11-year-old daughter, Sophia, and booked an Airbnb in Munich.

The first night, Rubanska woke up to calls from her family in Kharkiv.

“They said, ‘You were right to leave.’ … My mom could see bombs from her window,” Rubanska said. “But it didn’t feel right. I had a business, employees, and family in Kharkiv — I asked myself, ‘What am I doing in Munich?’”

While she stayed in Germany, Rubanska used her time recruiting volunteers to help others in similar positions cross the Polish border into Munich.

“I must have done that 14-hour drive from Munich to Poland 20 times,” Rubanska said.

Four months later, Rubanska realized she couldn’t pay for the Airbnb anymore and ended up crossing the ocean, settling in Northampton, Massachusetts.

“My case was easier because I speak English but I had no idea what to do with health care, education for my daughter, or insurance,” Rubanska said. “It’s important to have someone in the beginning to help you.”

The worst part about the refugee process is that the future remains uncertain, Rubanska said.

Daniya Ali ’25 said that it was wonderful that Rubanska felt comfortable enough to share her story, especially given the vulnerability of a first-hand account.

“I’m hoping that we can do more events like this at Amherst,” Ali said. “This was a really good step.”

Ali is taking a special topics class that focuses on storytelling as a way to treat trauma caused by the migration process, so she wanted to attend the event to meet people with knowledge of the subject.

Ali said that it was interesting to learn more about the technicalities behind the national system, and the differentiation of terms like immigrants, refugees, humanitarian parolees, and displaced people, especially given the agency of the individuals in each category.

“I’m looking forward to finding ways that we can be supportive without taking agency and dignity away from people,” Ali said. “There are power dynamics and complexities that arise from this work.”

Ali said she was struck by how bureaucratic and politicized the resettlement process is.

“You need a lot of money to help people, and that money is coming from the United States Bureau of Refugees and the state of Massachusetts,” she said. “I didn’t realize how much that influences what people can and can’t do with clients.”

In past experiences with refugees, Ali said, she has focused on building relationships with children.

“There is a psych[ological] study about how most refugees are brown and Black, while most people on the giving end tend to be white. There’s a huge cognitive dissonance as a child when only receiving from a white person,” Ali said. “How do we change that so that children realize that, with time, they too, can be on the giving end? We need more representation in resettlement work.”

Chris Tun ’25 is the son of refugees from Myanmar, and said he chose to attend the talk because “it was right up [his] alley and because there’s not much on campus about refugees and the process of resettlement.”

Tun grew up surrounded by refugees. Every Sunday, his family would drive to church in Clarkson, Georgia, a major refugee community, and congregate with fellow members of the Karen ethnic group. He also interned at Catholic Charities in Atlanta, Georgia.

Because of his volunteer experience, Tun was aware of how the refugee resettlement process worked but was able to learn more about state-specific actions during Tuesday’s Massachusetts-centered presentation.

Tun added that volunteering made the adverse effects of current events feel more tangible.

“We hear about the evacuation in Afghanistan and the war in Ukraine all the time, but we don’t actually see the outcomes of these global events in our daily lives,” Tun said. “Going to a refugee resettlement agency, you see the gravity of these situations. You see how much is going on that you’re not aware of.”

Tun said that he values the importance of a first-hand account, but also acknowledged the difficulty of sharing a traumatic story.

“I’ve heard stories from some refugees that are extremely traumatic. It’s definitely hard for some people to talk because it’s going to a place they haven’t reached a resolution with,” Tun said. “For [refugees] who can speak, it’s very important that people listen and engage with what they’re saying.”

Tun said that he would like to see more panels like this on campus, in order to promote public service and diverge from the preponderance of academic-based panels.

Comments ()