Paul Dano’s Directorial Debut in “Wildlife” Misses the Mark

Paul Dano has made a name for himself as a critically-acclaimed actor across a splay of successful independent films, including “Little Miss Sunshine,” “Ruby Sparks” and “Love & Mercy.” However, in his directorial debut “Wildlife,” Dano moves from in front of the camera to behind it.

The feature film is an adaption of Richard Ford’s 1990 novel of the same name. Dano not only directed the film, but also co-wrote it alongside his longtime partner and fellow actor Zoe Kazan.

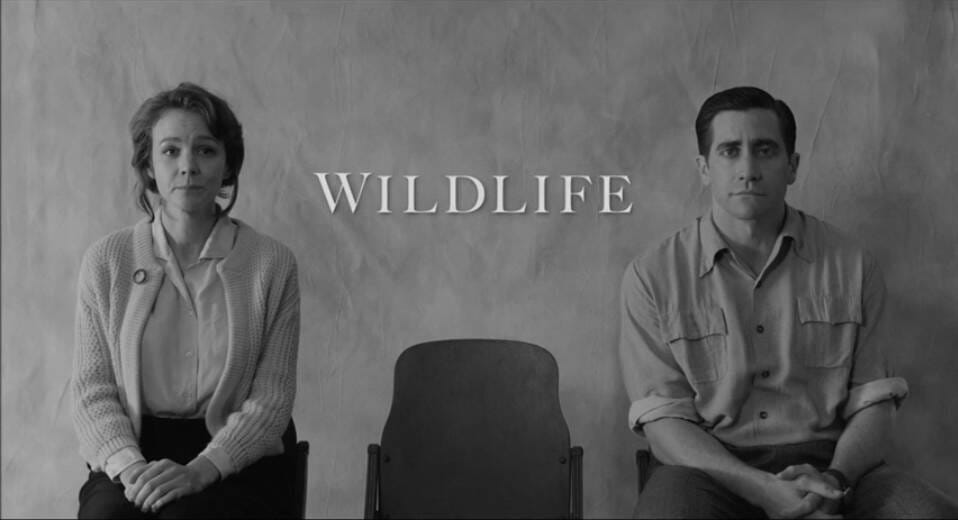

The film, set in the 1960s, tracks 14-year-old Joe (Ed Oxenbould) after his sudden move to Montana with his golf pro father, Jerry (Jake Gyllenhaal), and stay-at-home mother, Jeannette (Carey Mulligan). Shortly after their arrival, Jerry loses his job and becomes a destructive force in his family’s lives as he attempts to regain a sense of purpose.

His tyranny is only reined in when he hears of forest fires ravaging Montana’s wilderness and impulsively defies the wishes of both his wife and son by deciding to join forestry conservation efforts. While Jerry attempts to go fight the hellish fires, he neglects to realize the chaos that has been left in his absence.

Alone and unemployed, Jeannette loses all faith in her marriage and spirals into a depression. As his parents’ marriage rapidly decays, a new maturity is thrust upon Joe and he must struggle to find a sense of belonging, not only in his new community, but also in his dysfunctional home.

Throughout the first thirty minutes of the film, I consistently felt as though I was watching a poorly written student film. Maintaining my faith in Dano’s directorial abilities, I waited for the film to metamorphose into a driven narrative, but I was sorely disappointed when I realized that this wait would be indefinite.

Dano very quickly renders his first attempt to direct as juvenile in his lack of sincerity and thoughtfulness. Despite attempting to offer allure through dramatic scripting soaked in 1960s style, the writing feels clunky and immature — even when voiced by the respected Gyllenhaal and Mulligan.

This isn’t just the problem of working under a new writer and director. In 2016, Gyllenhaal worked seamlessly under first-time director Tom Ford for the production of “Nocturnal Animals.” Similarly telling the story of a dismantled family life, Gyllenhaal and Ford create a devastatingly beautiful film, which is something Dano is desperately reaching for, but entirely missing.

Perhaps Dano’s greatest directorial flaw is that he attempts to stay within a cookie cutter idea of what the modern indie film is: desaturated, quiet and occupied with lingering, cinéma vérite-inspired shots. The film is littered with beautiful, sweeping shots of Montana that are poignantly interspersed with awe-inspiring footage of the forest fires ravaging the landscape.

Yet as the film unfolds, the choice to establish the familiar indie aesthetic begins to feel clumsy and overtakes the narrative of the film. This wide lens approach seems to be somewhere between a reverent homage to Terrence Malick or Wes Anderson — understandable influences for Dano’s era of filmmaking.

However, the inflexibility of the movie’s cinematography and editing feels trite and paints its integrity into a corner. Nuance is not a necessity in film, but the borrowing of trite material is a sin.

The one great success of the film may have been an accident, considering the lack of intentionality that seems to characterize the rest of the production. The main character, Joe, lacks emotion throughout the film, making it incredibly easy for the viewer to project their own emotions onto the boy. Joe’s stoicism does not seem to be an intentional lack of character, but it conveniently primes him as a canvas for the viewer to paint themselves into the narrative.

Despite this potentially being the result of flat acting, this effect essentially crafts a role for the audience and makes the heart of the story much more touching. Dano’s attempts to be deep and compelling flounder under this questionable direction, making the film ultimately lack a sense of believability and originality.

Dano tries to tell the story of a teen boy’s dysfunctional family in the periphery of American life, but instead, he creates a film that lacks narrative and that will wash away in an indie market that is already oversaturated with dysfunctional coming of age tales — ones that are far more compelling than “Wildlife.” While I would not recommend this film, it is currently showing at Amherst Cinema throughout the week.

Comments ()