Q&A: Artist Radcliffe Bailey on Process, Creation and Acceptance

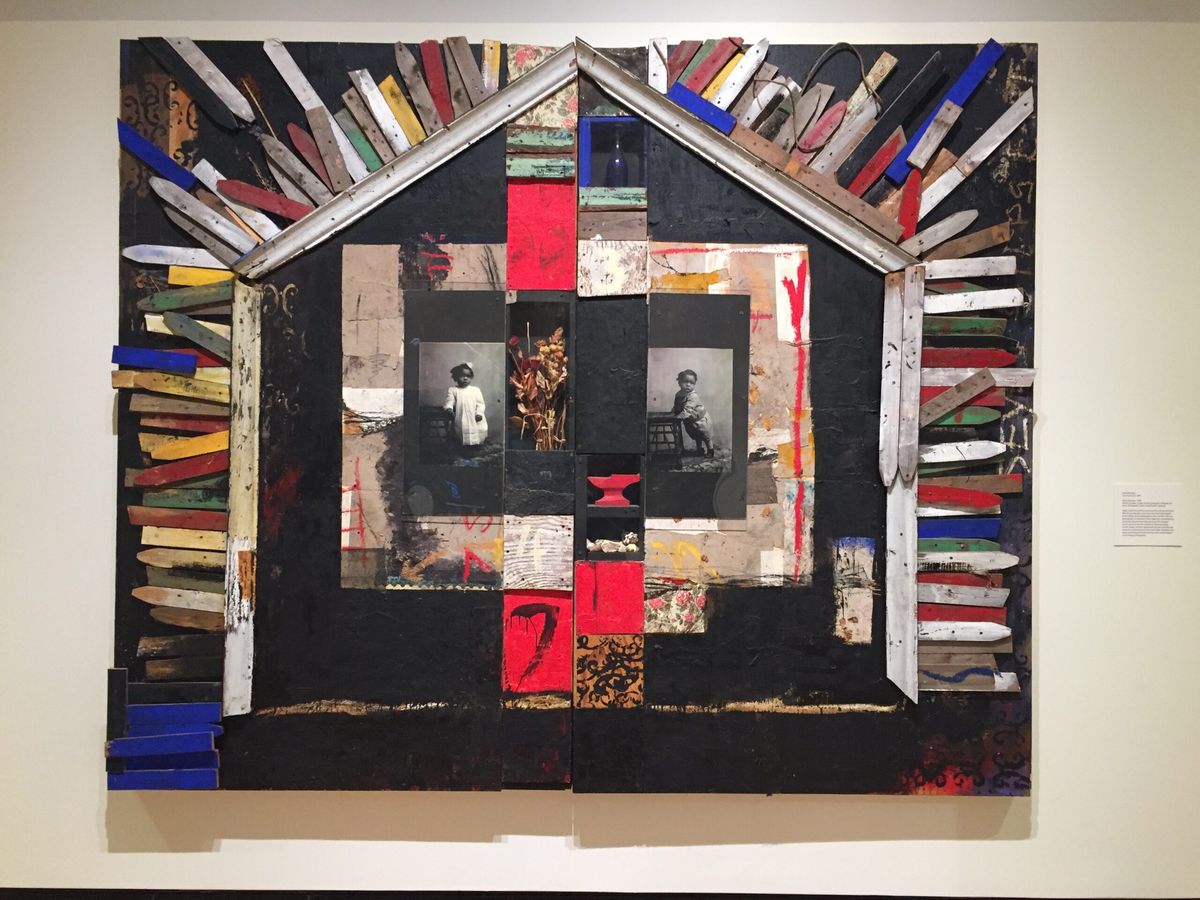

Radcliffe Bailey is an American artist based in Atlanta, who is especially known for his mixed-media, painting and sculpture work that centers around African-American history. One of his pieces, “Seven Steps East,” is currently on display at the Mead Museum as a part of the “HOUSE” exhibition. Bailey visited campus recently, and The Student had a chance to interview him.

Q: When did you first realize you wanted to become an artist? What was the first piece that you created that made you realize you were meant to be an artist?

A: Well, I was guided by my mother to go to art school. My first passion was to play baseball; I wanted to play baseball and all of my attention was guided toward baseball. But my mother created a school outside of school for me when I was in school — she used to take me to museums.

So, when it came to going to college, I wasn’t going to walk on and play baseball, so I went back to my mother, and we went to visit some art schools, and I decided to go to the Atlanta College of Art, which was close to mom at the time too. And it was a museum school; it was connected to the High Museum of Art, which I had spent a lot of time in as a kid, so it felt comfortable.

That’s when I decided to go to art school. But I wasn’t thinking about being an artist. I didn’t know what that really looked like. So, when I realized, “Okay I’m making art right now,” was probably my junior year of college. Everyone went away for the spring break, and I locked myself in the studio.

The studio didn’t have any windows and I realized I was working for over 24 hours, but I started to hit a note, and I started to feel good about the stuff I was making. That work itself pushed me in a certain direction. I started using objects from my family and things like that, and the work that’s actually here [in the Mead] is done two or three years after that with the same thoughts, somewhere in between painting and sculpture.

Q: Speaking of the multi-media aspect of your work, did you start out just doing one discipline or were you always working with multiple forms of media?

A: I got a lot of people inside of me, and each one of them I allow to speak in different ways. I don’t really try to make [one more present] one way, or one [prevail] the other way. I just allow them to be, and I have the freedom to go back in time and forward in time. So that’s me.

Q: Could you speak about the piece we currently have display in the Mead, “Seven Steps East?”

A: I was collecting objects and fences and things from houses — houses that were abandoned or being torn down. I’d go to empty lots and collect wood, and there was something about rebuilding a house.

I took the title from the fact that I was listening to Miles Davis, this piece called “Seven Steps,” so “Seven Steps East.” I started playing with numbers seven, three and four, dealing with numerology in a strange way.

The objects in the piece are also based around my interest in African art. At the time, I started looking at a lot of stuff from the Congo and African-American practices in the South, such as bottle trees. You’ll see an anvil, dealing with blacksmiths but also dealing with certain deities from Nigeria. So, it was really like a mixture of all of these different things that I think about, that I’m interested in, and I’m trying to draw a connection to my own personal DNA.

In certain areas, you’ll see almost like a brand, and that brand was taken from a store that was in my neighborhood, and I was representing the blacksmiths that came from the Carolinas and New Orleans, by using that brand.

The photographs in the piece are images of twins that were in a family album that my grandma gave me. A lot of times you get these old photographs, and I wanted to give them life rather than them being in a book in a corner. So, they have life now. I also painted with wax and tar and wallpaper, using all kinds of materials from house building.

Q: What is your process in creating a piece of art? Do you always look for something to center your pieces around or do you usually have the idea first and then look for a specific object?

A: My process is very loose; it’s very free. I collect things, and I read a lot. I have to be around objects for a while. I almost have to put a certain patina on it so it can have a life, a new life, because I’m using objects that have a past. I still pinch myself and say, “Woah, am I doing this?” or “This is what I do … Oh man, how lucky am I?”

It’s also stressful because I’ve got to get myself in the headspace all the time. I try to go to a place where it’s soulful, it kind of has a lot of pleasures and pains all mixed up together. It’s like the blues, there’s a screaming, and there’s a kicking, and there’s a certain kind of emotion that I deal with to make work, so it’s hard.

Q: Do you have a piece of work that’s your favorite or you think is most important?

A: They’re all kind of important, in a way, but I like to compare it to pages in a book; I like the most recent thing I’ve written.

When I think about that piece that’s here [at the Mead], it’s real important because it was the first show I had in a gallery that I got a major review for. John [Wieland, the owner of the pieces on display in the “HOUSE” exhibition] was the first major collector to purchase one of my works, so for me that was a major moment in my life because I had to learn to let go of my work in a certain way, even though it was so personal to me. I had to let me go and have its own life. And I’m able to see it today, which is kind of eerie and strange.

Q: Any advice for someone who wants to become an artist?

A: A friend of mine who was a curator told me, “Always consider yourself to be an emerging artist, always emerging — never ever date yourself.”

So I try do this; sometimes I get a little nervous when I go, and I see older works of mine, ’cause I see it and I’m like “I want it do this to it, I want to change it, and I can’t do that.”

I was always insecure about what I was saying. I was insecure about every mark. I was unsure — I just put it out there. My first belief is that I never make a mistake when it comes to making marks, so I’ve learned to live with that.

Comments ()