Rachel Sussman Speaks on “The Oldest Living Things in the World”

Outside, rain was falling, droplets slowly sliding down against the outside of the glass. It was a quiet, cozy Wednesday afternoon in Fayerweather Hall, and we were learning about the oldest living organisms in our world, and the immense beauty of “deep time” via photography, a medium that captures the present, the ephemeral.

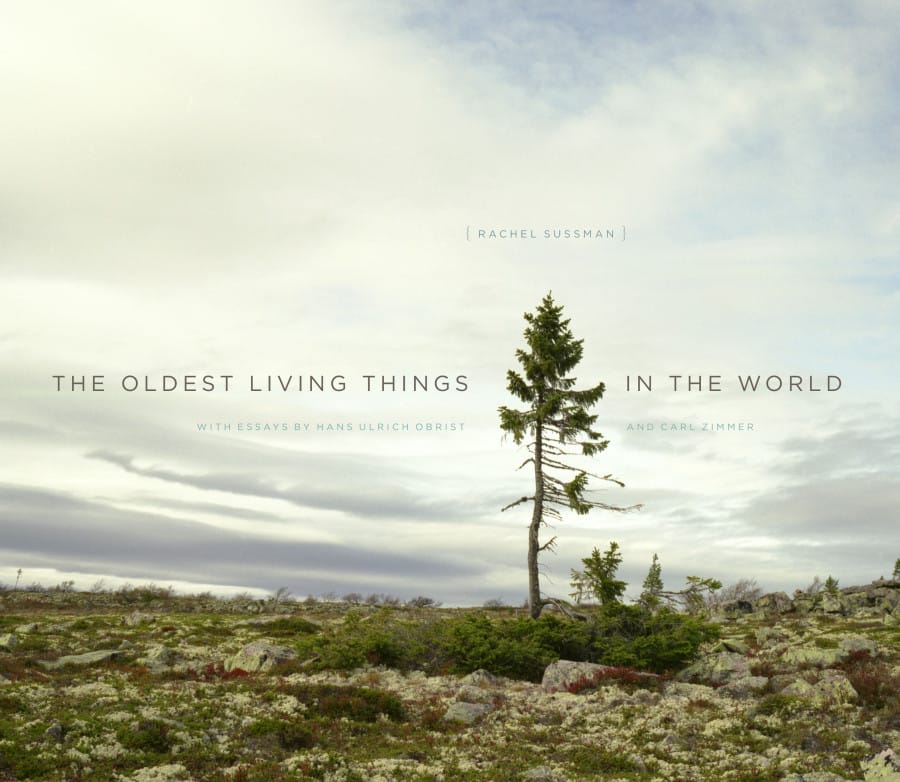

This past Wednesday, April 6, Rachel Sussman, an artist from Brooklyn, New York shared her thoughts and stories with Amherst students, professors and the greater community from her photography project documenting the earth’s oldest living things called “The Oldest Living Things in the World.” It was a 10-year process with hundreds of thousands of miles traveled and dollars spent and resulted in her own traveling exhibition and a New York Times bestselling book.

In her work, Sussman focuses on connecting art, science and philosophy in a way that reinvigorates engagement between the minutiae present within each field and subfield. Her work tells a more accessible, bigger picture story about the ancient than the dense, highly specific, largely unrecognized research papers that already exist on the topic.

Sussman’s quest to document pictorially the oldest living things began in Japan in 2004, where chance, rumors and her sense of adventure led her to travel from the mainland to deep inside an isolated island off the coast, reached by train, then ferry then a two-day hike. At the end of her journey, she came face to face with the ambiguously 2,180 to 7,000 year-old Jomon Sugi Japanese Cedar. Despite its awe-inspiring longevity, Sussman does not recall feeling any incredible connection to all this history, the thousands of human lifespans that this tree has seen, in that moment. She took photos, and the shutter clicked, but nothing in her did.

Yet, intrigued by the age of this tree still, Sussman began to research the other oldest living things on the planet to photograph them as well, and hopefully create a compilation of deep time that people living in places as diverse as these ancient beings could connect with. Sussman’s research took her to Elephant Island in Antarctica, South Africa, Copenhagen, Chile, the bottom of the sea off the coast of Tobago, Sweden, Florida and many more near and far. Species Sussman found ranged from different types of trees to shrubs to various bacteria and moss to coral and so on; the ages of these ranged from 2,000 to 60,000 years old. Some had adapted to very extreme conditions, while others thrived extraordinarily in what we would call the normal.

In her presentation of this adventure, that actualized as an art product but also the fulfillment of her lifelong dream to travel and penchant for wanderlust, Sussman told stories of her own personal growth as well as the process of discovering, locating and researching these organisms.

In connecting the world of science and art, Sussman swiftly exited her comfort zone and delved into dealing with specialists — those who had researched these long-lifed creatures and produced papers filled with the scientific specifics of longevity.

“Nine times out of 10 the scientists I contacted were happy to help,” Sussman explained. “Levels of enthusiasm ranged from sending me the GPS coordinates to inviting me to join their own expeditions to visit the species.”

On one expedition, she tested her own personal philosophy of only eating what she could physically harvest or kill herself with a clear conscious. On the wind-ridden, seemingly desolate landscape of Southern Greenland, Sussman stuck her hands into a chilled stream and extracted, skinned, cooked and ate one of the hundreds of swarming fish that flourished beneath

the surface.

The series of photos induces reverence for nature, and recognizes climate change. Since she started working on the project, an over 3,000 year-old underground forest in South Africa has been bulldozed over, and a 3,500 year-old hollow tree just outside of Orlando was burned down by some careless kids smoking meth. The fragility of the seemingly immortal recognizes the possibility of instantaneous destruction.

Sussman’s “The Oldest Living Things in the World” exposes many of the extraordinary, rare instances where life extends far, far beyond the scope of ancestral memory. A human life aligned next to these grand, unfathomably old species becomes, as the artist herself describes, somewhat marginalized yet glorified, so that we become the minutiae that’s important.

Rachel Sussman is currently working on a project on deep time and deep space in tandem with SpaceX, NASA and CERN supported by the LACMA Lab. She has two upcoming exhibitions at the MASS MoCA — “The Space Between” beginning on April 16 and the ongoing “Explode Every Day.”

Comments ()