Rebecca Picciotto: Stewarding Stories With Care and Perspective

Rebecca Picciotto has a deep passion for connecting with people through journalism. But she also understands just where journalism can fall short.

“If my job was to have a conversation like this every day with someone, I would really, really love that, actually,” said Becca Picciotto ’22.

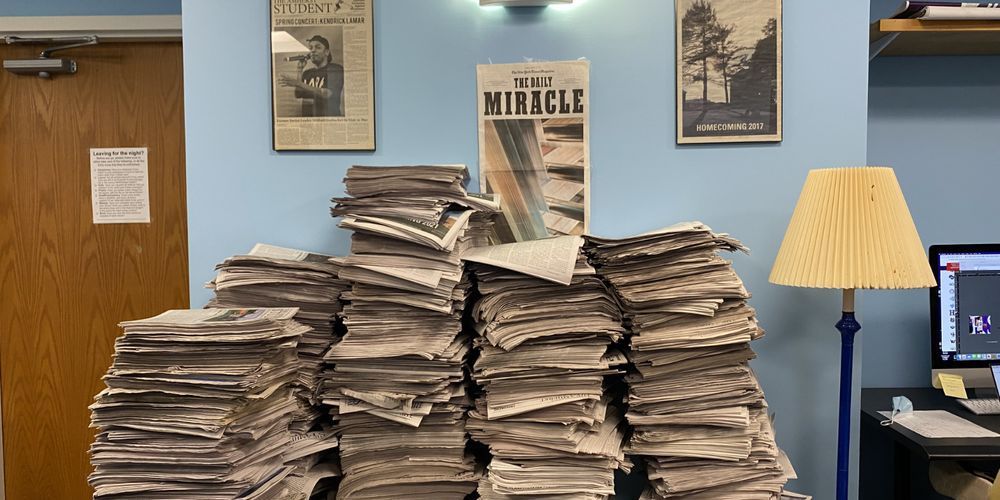

It was over three hours into our interview, long after we had strayed from the list of questions I had prepared. We were sitting across from each other under the fluorescent light of The Student’s newsroom in the basement of Morrow Dormitory, where Picciotto had spent many a long night as editor-in-chief. At this point in the interview, she had started talking about her idea of starting a Substack and dedicating it to writing profiles of people.

“The thing I like about journalism is talking to people, and I feel like profiles give you an excuse to actually talk to someone for a while,” she explained. “[And] of course there are ethical questions there, but in terms of story selection, I feel like it’s a bit more straightforward. I’m really cognizant of [the fact that] the stories that get represented in the news are a product of the journalist’s story interests — what they find newsworthy is their own biases, right? Everyone, though, has a story.”

In many ways, the conversation was emblematic of how Picciotto approaches journalism: with a deep passion for storytelling and generosity in connecting with others, but a sober understanding of how the work can be limited by one’s own subjectivity.

And while this interview was the first time I had heard Picciotto explicitly express her love for connecting with people, it didn’t surprise me. I first met Picciotto during the remote semester last spring, when I joined as a new member of the editorial board. When the editorial board would connect over Zoom for its weekly meetings, I was struck by her level of engagement even in the virtual space, as her warm smiles reacting to the discussion would often cut through the Zoom awkward that we were all too familiar with.

I also eventually became aware of how Picciotto brought this same attentiveness and care to her writing, telling stories with a kind of artistry and creativity that I, accustomed to the more straightforward style of news writing, often struggle to access. Funnily enough, just days before Picciotto told me about her dream of profiling people in our interview, after tasking each of the paper’s editors with writing their own profile for this issue, I had told a few of them, “You know who writes good profiles? Becca does.”

It’s definitely a bit daunting writing the profile of someone who has written some of the most beautiful profiles I’ve read out of The Student. But in the same way Picciotto approached the many daunting tasks she faced in her tenure as editor-in-chief, I will do nothing less than try to rise to the challenge.

Finding Connection Through Storytelling

Picciotto was first introduced to news writing through an assignment in her eighth-grade English class. Inspired by the experience, Picciotto decided to join her high school newspaper freshman year — and in doing so, fell in love with the reporting process. “It didn’t feel like hard-hitting journalism, but … I think that was just fun for me as a 14, 15-year-old — I was like, ‘Oh, I have a purpose here.’”

This sense of purpose is what eventually led Picciotto to The Student during her sophomore year at Amherst. She noted that she was very sporadically involved with extracurriculars her first year because she wanted to see what lay beyond the regimented lifestyle she had followed in high school. “I had [a] good year of being very fluid and stuff like that, and I definitely think I was coming back to wanting to feel a little bit more connected to the community and just wanting to find my role here a little bit more,” she said. A posting in the Daily Mammoth that fall about a managing opinion editor opening caught her eye, and soon, she was back in the newsroom.

That semester, Picciotto also pursued an investigation of how Amherst’s position as a college town uniquely influences its housing dynamics for a piece published in The Indicator’s Fall 2019 issue, “Home.” Although the final product wasn’t “hard news,” she was glad to get a taste again of the reporting process she enjoyed so much in high school.

After the pandemic hit the following semester, Picciotto began writing news stories for The Student, documenting the experiences of a community adapting to remote learning and an uncertain future. And in Fall 2020, amid a remote semester she described as mentally difficult and marked by disconnection, Picciotto started “Tusk Talks,” The Student’s first-ever podcast, continuing to tell the stories of Amherst students from hundreds of miles away.

Coming Into Her Own in the Newsroom

But it took a while for Picciotto to get comfortable in the newsroom. Although she had ended up running her high school paper, her lack of formal training left her feeling intimidated when she first joined The Student. “I was really terrified, actually,” she said with a laugh. “I think I just got into the space and was like, ‘I’m gonna take this super slow and just do exactly what I’m told.’”

While the editing eventually became more routine and the crisis of keeping the paper going through Covid allowed her to feel more in solidarity with the rest of the newsroom, Picciotto was still shocked when then-editors-in-chief Natalie De Rosa ’21 and Olivia Gieger ’21 approached her that spring about becoming editor-in-chief. “I was genuinely like, ‘I’m confused,’” she said. “But then with that confusion was like, ‘Oh, would I actually do that?’ Because I had literally never thought that was on the table.”

Becoming editor-in-chief presented an opportunity to integrate herself even more in the community, Picciotto said, as well as an opportunity to grow through the difficulties and demands of the role. Ultimately, the decision made itself, with Picciotto joking that the only thing holding her back at all was her early-pandemic optimism that study abroad would still be an option her junior year.

And while the role continued to make her nervous, Picciotto embraced the challenge with nothing but an openness and drive to improving herself. Noting that co-editor-in-chief Ryan Yu ’22 seemed to have from the start a precise intuition for the work that she felt she was just beginning to develop, she said she expected that “there would be a learning curve for me, so I kind of did my best to not hold anything back and just learn.”

In her own words, Picciotto still doesn’t think she has a “rock-solid intuition,” but she does concede that she grew into herself as an editor-in-chief. “You kind of have to,” she said. “That’s a beautiful part of the role.”

“Becca would always insist that I had more of a particular intuition for news,” said Yu. “I’m not sure that’s true, and more specifically, even if I did have that intuition initially, I think she has that intuition now.”

Yu added that Picciotto’s determined nature and more systematic approach was often what allowed them to see things through “in a more direct and detail-oriented manner.” “I think we complemented each other very well,” he said.

“I don’t think that she always gives herself enough credit for things that she does,” said her friend Gavi Forman ’22.

Grappling With the Shortcomings of Journalism

Indeed, it was from Picciotto that I was first introduced to thinking consciously about the framing of a news article, the importance of which only became more apparent across many production nights, when she and Yu would stay up agonizing over how to present a story in a way that would do the most justice to those represented in it.

“As much as you can just consume an article and a headline, there are so [many] choices that have been made every step of the way that decides why you’re reading it the way you're reading it,” said Picciotto. “Some of our conversations were about how to report on something or how to frame something in a way that wouldn’t be harmful. But that’s a really, really hard question.”

A philosophy and math double major, Picciotto would also bring a grounding in philosophy to broader ethical discussions with Yu about journalism at large. In our conversation for this profile, Picciotto spoke often about the harms journalism has caused historically and continues to cause in the present.

“As much as journalism has moral value and moral positive value, it also has equal, if not more — in the way it’s been practiced — moral harms, and has been an institution that has harmed communities, as it has done its own work,” she said, “like the way it has created narratives about communities and people and has been extractive about that, using people as sources and characters in the story rather than human beings.”

“Becca was especially cognizant of her own positionality,” noted Yu.

This awareness motivated Picciotto’s thesis in philosophy about the norm of objectivity in journalism, which — particularly in the wake of the killing of George Floyd — has come under fire for acting as a stand-in for white perspectives, instead of serving as a means toward the pursuit of truth. She explained that she was interested in this debate because she had always thought objectivity was “a pretty essential ingredient” in journalism, but didn’t feel it was her place to stand up for it. “I was like, I’m a white person. Because the version of objectivity that journalism currently functions under is a mask for white values — or caters to a white mainstream — it was hard for me to say, ‘Let’s uphold objectivity.’”

In her final argument, Picciotto maintained that objectivity is essential to doing journalism, but clarified what, in her view, has been miscommunicated in the debate. “Historically, journalism has said that values — personal bias, subjectivity and all that stuff — are contrary and cannot coexist with a norm of objectivity,” she said. “I argue that objectivity is enhanced by personal values and understanding your perspective. First of all, objectivity does not exist — you cannot have a ‘value-free objectivity’ [because] we are perspective-inhabiting creatures. If I acknowledge that perspective, I can be more objective in terms of understanding where I can’t see certain truths.”

While joking that the process of finishing the thesis was akin to an emergency C-section, Picciotto feels more able to deal with the question of objectivity now. “I always was really ready to concede [to the anti-objectivity stance], but now I think this idea that [the assumption of value-free objectivity] is just an incorrect application of objectivity and not a problem with the objectivity norm itself helps me, because I’m not necessarily just gonna say we shouldn’t be objective.”

“There’s an ideal of objectivity that we might never achieve,” she concluded. “It’s not to say it’s not worth pursuing. But it is to say that we should be aware of the misapplications that are currently in this industry.”

An Open-ended Path Forward

The ways that journalists can do harm is still something Picciotto is coming to terms with, particularly as it relates to pursuing a career in journalism herself. “There’s a dilemma at every point,” she said. “And you kind of have to accept that.”

After graduation, she’ll be completing an internship with the Wall Street Journal to try to figure out whether or not she can accept it. “It’s three months and then open-ended,” she said.

Whatever Picciotto chooses to do, I’m confident that she will continue to touch lives through the care with which she connects with others, all while leaning into any challenges she encounters along the way.

And if she ends up making that Substack? I’ll be the first to read it.

Comments ()