Remembering Jobs, Forgetting His Haters

The dust has, for the most part, settled. Steve Jobs’ passing has been covered by every tech journalist from Walt Mossberg to Jon Gruber, each offering his own personal memories and insight into what made Steve special. Individuals have recounted their email exchanges with him, posting his mono-syllabic replies on the internet. I imagine, in other newspapers at other colleges, other columnists have written other articles about just how important he was.

I never met Steve Jobs. He never responded to the one email I sent him (a complaint about the dock in Snow Leopard). Even if he had, I doubt any memorial thoughts I could offer would even begin to rival Stephen Colbert’s sweet, understated, on-air response to a typical Jobs email: “Right back at ’cha. Thanks for everything.” The tone of that email, coupled with the millions of Facebook statuses following the announcement, reveal a remarkable sense of personal connection between Steve, Apple’s customers and consumers at large. And that’s what I think my article can offer insight about: our connection to him and our response to his passing.

Few will argue that Steve was a saint. He once lied to co-founder Steve Wozniak about a bonus, keeping the funds to himself despite Wozniak’s having done most of the work. He dismissed Bill Gates’ philanthropy as “unimaginative.” He exploited the transplant waiting list system in order to obtain a liver before other patients. Even now, Apple still contracts its manufacturing to Foxconn, and remains too quiet about employee conditions there. We should acknowledge his flaws, but we also didn’t know him as a person. Now is not the time nor is this the forum to speak ill of the dead. And some critics should know better.

So, quite a few showed up in those status updates following the announcement of Steve’s death. Others showed up in blog posts. Whatever their forum, they waited mere hours before repeating the hackneyed refrain that Steven Jobs was a fraud, Apple’s products were overpriced and his customers were blind, tech-illiterate hipsters who had the wool pulled over their eyes. Their tactless timing aside, I think it’s time we dismiss those stale claims. What they meant to say was “I do not like Apple products; I will not buy them, and I do not understand those who do.” And we can’t fault them for that.

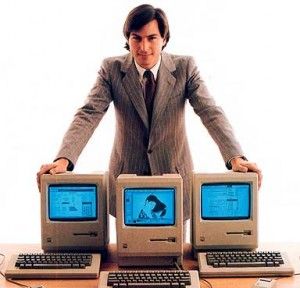

But Jobs was not a swindler, and his customers are not sheep. Macintosh products do, in fact, cost more. Their hardware specifications are often, in fact, less impressive than competitors’ offerings. Many Apple customers are, in fact, less tech-savvy. And that’s exactly the point. Since the beginning, Apple’s unique strength has been software design with an emphasis on user-friendliness. Apple can charge the prices it does because, in Job’s words, “In hardware, you can’t build a computer that’s twice as good as anyone else’s anymore but you can do it in software.” Hardware is a race to the middle in computing sales; if you want better performance, you’ll have to pay more. Financial and critical success instead lies in simple, spectacular software design, and that’s where Jobs and Apple found it.

Jobs’s greatest contribution was his zealous perfectionism in the pursuit of something new, something better. He sent project after project back to the drawing board. He scrutinized details, forcing revisions and re-designs. He threw fits when engineers missed deadlines. But he gave them the space and resources needed to work; Jonathan Ives’ secret workshop is the stuff of legend at Apple, an industrial designer’s dream. And, through all these meticulous demands, Apple’s products debuted to stunning reviews.

I think Apple can maintain that enthusiasm in Jobs’s absence. Jobs made preparations, starting an Apple University to pass on his methods and hiring the Dean of Yale’s School of Management to head the program. Tim Cook has been managing logistics at Apple for a while now, and he’s held it together through a huge product release. Whether Apple can hold its place at the cutting edge, dominating new product niches and markets is a far more complex question. Its answer is distant, and I don’t think we have the tools to make that prediction now. But Jobs has done quite a bit to preserve his management style.

In the end, you can’t dismiss his achievements, but I think you can call Steve what you want. Wait a little while out of respect, but you can call him an egomaniac. You can say his management style was insane, his arrogance astounding. He famously asked John Sculley, former CEO of Apple, whether he wanted “to sell sugar water for the rest of [his] life” or come to Apple and “change the world. ”You can say that’s a ludicrous statement — crazy, even — and I think he’d like that. I think he’d love it. Go watch an old “Think Different” commercial, and you’ll see what I mean. Rest in peace, Steve, and “thanks for everything.”

Comments ()