Retrospective on “The Sandman”

“The Sandman,” a comic series written by Neil Gaiman, recently received a Netflix adaptation. Ross Kilpatrick ’24E reviews the comic, which thrills with cosmic ideology but sometimes suffers from a slow plot.

“The Sandman” is a weird comic. The more I try to succinctly describe it, the more I lose my grasp of it. “The Sandman” is a comic about a character named Dream who rules over the kingdom of Dreams. The comic is composed of a number of different stories, or “arcs,” each of which is an individually contained story with recurring characters. Among these recurring characters are Dream’s siblings, the Endless, who are embodiments of different ideas which have driven human affairs for eons; Destiny, Desire, Delusion, Despair, and Death. So in a very literal way, “the Sandman” is a story about ideas. It’s about the ways in which ideas change people and history.

But that makes “The Sandman” sound overly analytic and preachy. “The Sandman” is also a fun comic about demons and gods and God and many different mythologies. And it’s about humans who live for a long time. But it’s not above simple action. The first arc of the series follows Dream as he tries to regain his powers after having been held captive for 70 years by cultists trying to get to his sister Death, confronts an escaped serial killer nightmare, and repairs his kingdom. If nothing else, “The Sandman” is an immensely creative comic.

But “The Sandman” is also a mixed bag, in a lot of different ways. Dream is a weird choice for a main character. He’s inhuman, literally and in terms of character: often aloof from the reader, his primary loyalty seemingly to his kingdom and the rules it follows. The reader rarely gets a look inside his mind or his thought process. We can only guess at what he’s feeling through how other characters react to him. Dream often operates through an archaic system of obligation and revenge, which seems more appropriate for the Code of Hammurabi than for a protagonist.

Sometimes, though, his facade breaks, and “The Sandman” hinges on these key moments that humanize Dream. But those stories, just about Dream, sometimes sag. The first arc is probably the strongest of the series, and the last one, instead of finishing triumphantly, at times feels a bit cheap and sudden. Still, Dream is a great character, and he is left in a great place by the end of the story. But his stories alone are not enough to make “The Sandman” a great work.

What I really think makes “The Sandman” special is everything around Dream. Dream is a focal point of the universe, our entry point into this strange and wonderful world. But we often leave him, and he’s sometimes the least interesting part of the stories. Many of the arcs of the series devote a large amount of time to individual human characters.

Rose in the first arc stands out. She is the granddaughter of a woman who went into a coma induced by the disappearance of Dream. Much of the first arc is devoted to Rose’s curiosity about her grandmother. This is a small but emotionally compelling plot, which runs alongside Dream’s quest to regain his power and kingdom. Characters such as Rose are effective because they provide a real sense of empathy and connection to the world. And there are a lot of issues which are one-offs, following characters which are often never seen again in the comic. These are some of the characters that really stay with me. The people affected by the Endless, by these literalized ideas.

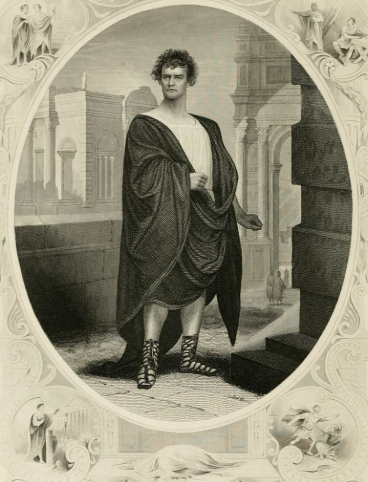

In one of the last issues of the comic, an emperor’s exiled advisor is asked by Dream to come with him and advise him. The advisor declines, he is still loyal to his old emperor and devoted to serving his sentence. It’s a simple story, but it shows Gaiman’s ability to focus on psychological and emotional reality as a major driving factor and interest within his stories. These one offs are engrossing exactly for their compelling portrayal of the struggles of these otherwise mundane people.

Another one of these tiny stories, which plays out in the background of the final arc of the series, shows a man grappling with the death of his father, who he didn't really know. These are deeply compelling stories within “The Sandman.” And I think Gaiman understands this. The final three issues of the main run of “The Sandman” are individual, one-off stories. The final one is mostly about Shakespeare struggling to write plays. That’s how this sometimes cosmic series ends.

The sense of variation isn’t just present in the stories. The art can vary from issue to issue and arc to arc, which creates an experience which is inconsistent in a strange way. None of the individual comics are bad. Taken individually, they’re each pretty great. Gaiman, like any good comics writer who doesn’t draw, possesses the ability to vary his stories and writing to the people drawing for him, so that the tone of a story matches the look of the issue.

But taken together, the series’ art creates an odd patchwork. There’s something to be said about a series coalescing around a single artist and a single tone — becoming effectively controlled and punchy. The excellent graphic novel “Watchmen,” by Alan Moore, is one example. “Watchmen” is all drawn by Dave Gibbons, and, as a result, it feels tonally cohesive in a way that “The Sandman” never does.

While reading the story, this sometimes disturbed me, but it also made me more aware of the artifice of the pages. Issues of the comic, which for readers in the ’90s were separated by months, were for me only hours apart. Standing back from the work, I can now see the tapestry these issues form, the whole, and I think in taking this approach they created something which captures the tonal range of the stories Gaiman was trying to tell through “The Sandman,” and captures something essential about “The Sandman” universe itself.

Because, ultimately, “The Sandman” is not a narrow aesthetic experience. It’s even hard to treat “The Sandman” as a singular work, as something like “Watchmen,” which aims at one ultimate goal. “The Sandman” has, in a sense, a beginning and ending, but it also has a million digressions. It’s not a novel, it’s a mythology of ideas, and the varied ways they affect and interact with humanity. It’s a series about destiny, death, desire, delusions, and dreams. It’s ultimately sprawling and given out piecemeal.

“The Sandman” is a great comic series. There’s no doubt about that. It’s getting a Netflix adaptation for a reason. But it’s not a seamless thrill, and that’s okay. What it lacks in consistency, it gains in the ability to zoom, from one issue to the next, from the literally cosmic to the deeply personal, to the ways in which its gods and demons and, most of all, its ideas affect and destroy individual human lives. It’s a comic about almost everything: sometimes subtle, sometimes bad, sometimes great. In the last issue Dream states, “I am not a man … I do not change … I am a prince of stories, but I have no stories of my own.” That is, ultimately, what “The Sandman” is trying to challenge. It’s trying to give stories their own story.

Comments ()