South Hall Through the Ages

Contributing Writer Stormie King ’25 recounts the extensive and peculiar history of Amherst College’s South Hall based on her archival research in the Department of Art and the History of Art.

South Hall, originally called “South College,” began its life when indoor plumbing was unheard of, when fireplaces were more for warmth than ornament, and when Amherst College still trained young men to be missionaries. South was the first building erected on campus. It was built before the college had a president, a professor, or students, and well before the college would receive its official charter in 1825.

Today, South serves as a first-year dormitory, housing students from all over the country and the world. This summer, my research with Gretchen Rabinkin, a visiting instructor in art and the history of art, dove into the lengthy architectural history of South. The following timeline provides insight into the fascinating past of the building that started it all.

Aug. 9, 1820

Zephaniah Swift Moore left Williams College with plans to open another institution — what would ultimately become Amherst College, of which Moore would be the first president. When deciding on the location of the college, Northampton was originally in consideration, but Amherst ultimately won out due to the influence of Noah Webster, famous lexicographer and president of the Amherst Committee, and because of a generous donation of land from Colonel Elijah Dickinson. Webster had lived in Amherst for many years, and he favored the hill in Amherst because of its proximity to “the geometrical center of territory,” and because “the refreshing breezes are most necessary for men of study.” Interesting points, dictionary man.

Once the location was chosen, building commenced — the college needed a building for instructional purposes and for housing students. No architect is credited for the plans of South Hall, but former college president Stanley King’s book “The Consecrated Eminence: The Story of the Campus and Buildings of Amherst College,” emphasizes the communal effort of building South Hall. Materials such as lumber, sand, bricks, and lime were donated from all over Western Massachusetts, and men and women of the town took part in building tasks, big and small.

William Seymour Tyler ’1830, a professor of Greek from 1836 to 1893, interviewed people around at the time and summarized that it was “a busy and stirring scene such as the quiet town of Amherst had never before witnessed.” On Aug. 9, 1820, the cornerstone of South Hall was laid and the foundation was finished: The building was on schedule to be completed by Fall 1821.

Sept. 19, 1821

On Sept. 19, 1821, Amherst College, then called “The Charity Institution,” opened its doors for the very first time to a student body of 47 students. The college had a president (Moore), one building (South College), and two professors. Until North Hall was opened in January 1823, South College was the home of all college happenings.

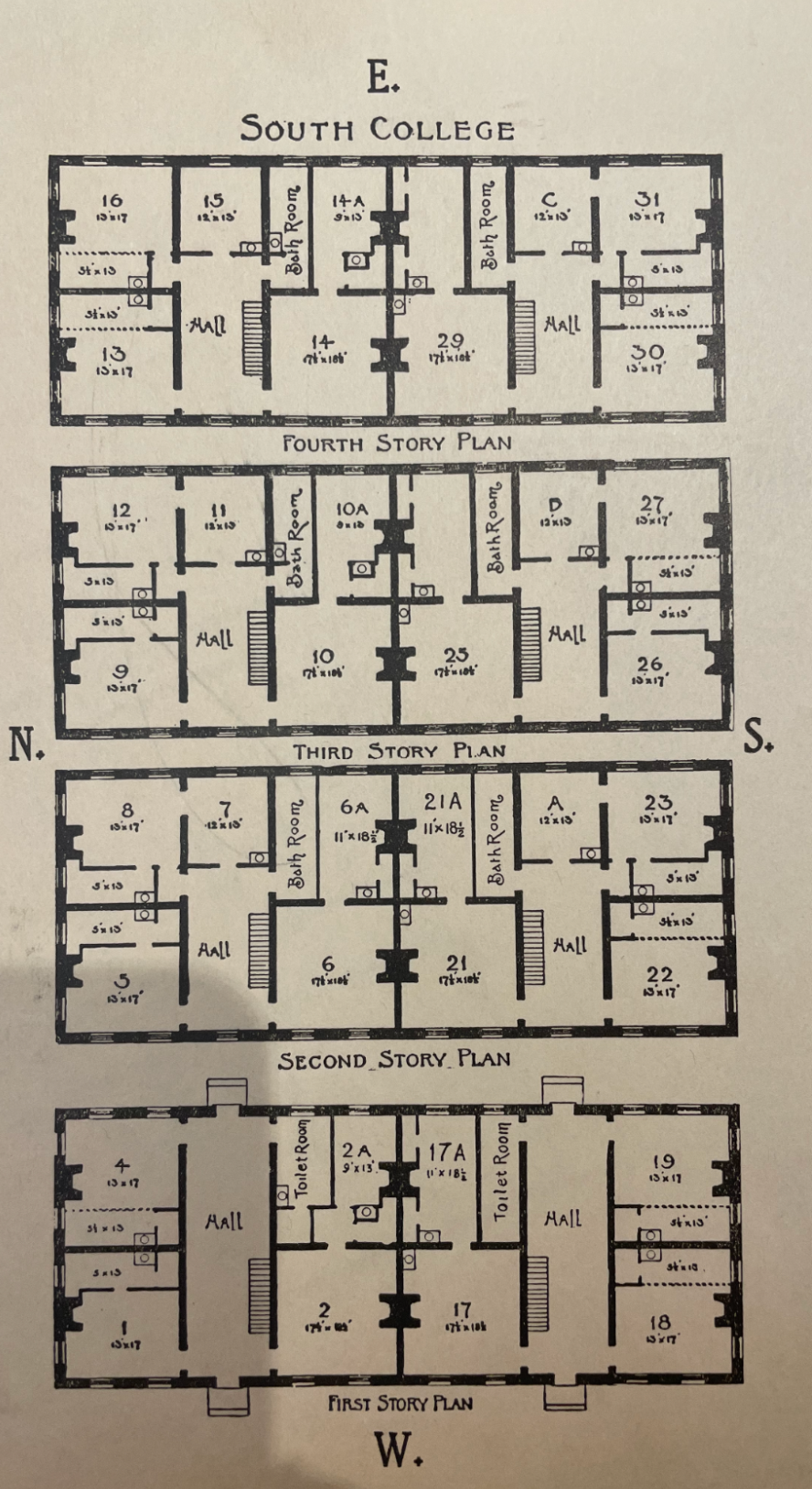

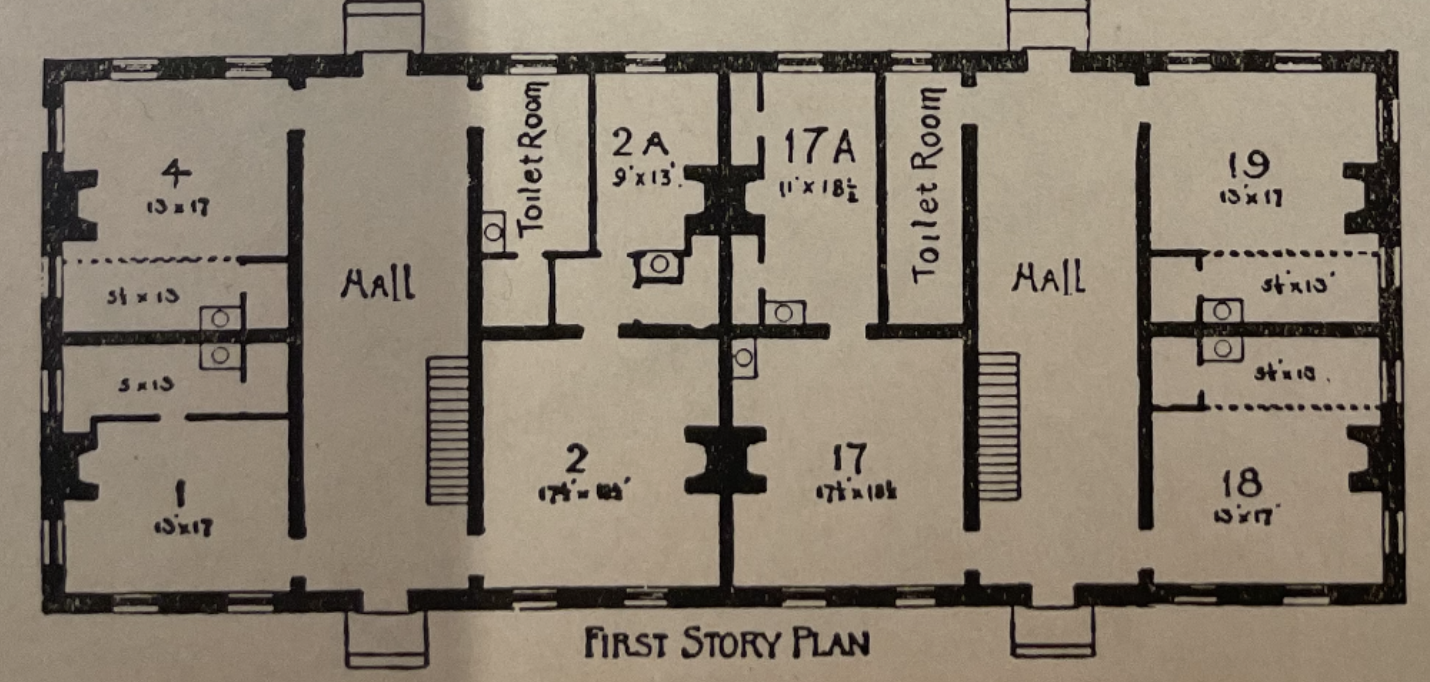

The building contained 32 rooms, with eight per floor, and the building followed a “double-entryway” or “staircase plan.” Although uncommon today, this plan was popular in schools like Oxford and Harvard. With four exterior entrances, each entrance basically functioned as a four-room suite because you could not access all eight rooms from every door — there were two entrances for rooms on the north side, and two entrances for rooms on the south side.

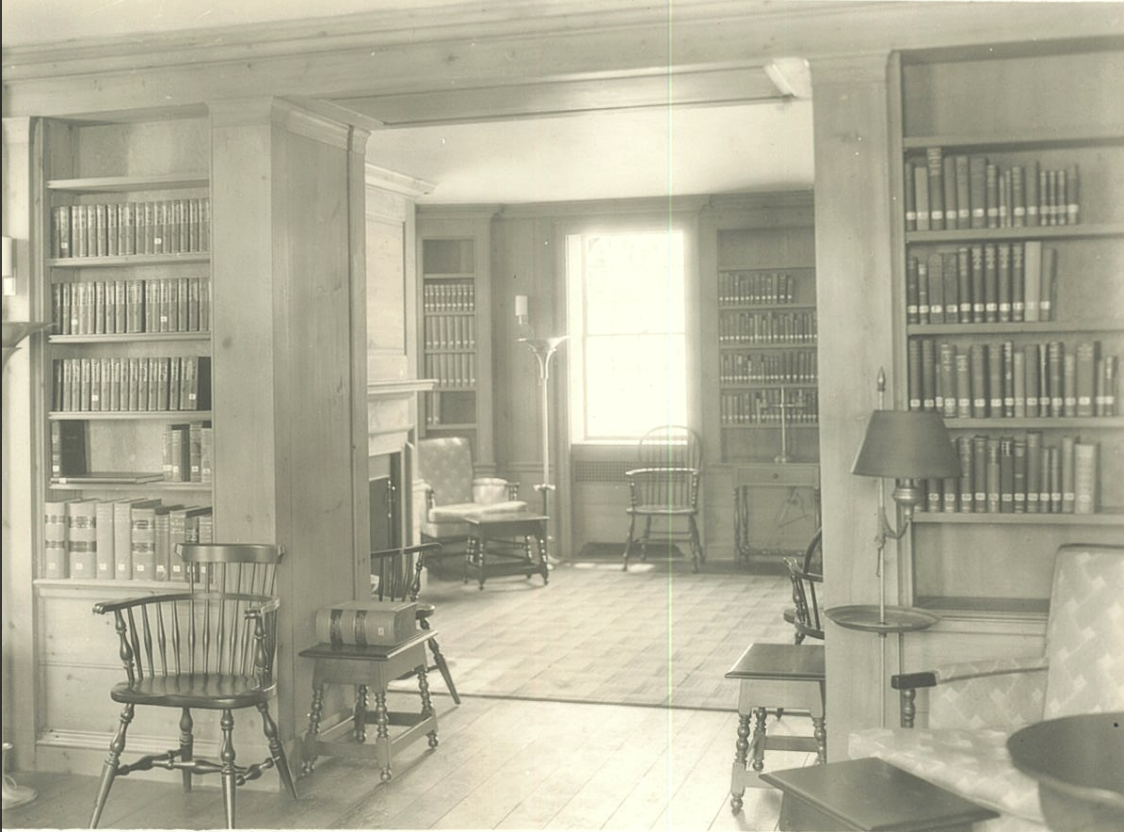

It was not uncommon for students to host their classes in their bedrooms, bringing chairs in for other students and the professor to sit. In “The Consecrated Eminence,” King details two seniors who hosted their “senior recitation” class in their bedroom on the fourth floor of South. College amenities at the time included a college well and an outhouse outside the dorm. Students were also expected to chop their own wood for their fireplaces from the abundance of trees near South Hall. The college’s library, then comprising only 700 volumes, was housed in the north entrance of South for two years and contained in a single bookcase measuring six feet in width.

Jan. 1823

North College opened and served as the new academic class building, so South College was used primarily as a dormitory. Some students lived in boarding houses near the college, as there was still not enough space for all students.

Feb. 28, 1827

Johnson Chapel was completed and dedicated. South and North served as full dormitories, while Johnson Chapel housed all academic spaces as well as the titular chapel.

In the following decades, Williston Hall, the President’s House, the Octagon, Morgan Library, the Appleton Cabinet, East College (on the current site of Stearns and James), Barrett Gymnasium, Walker Hall, Stearns Church, Pratt Gymnasium (now Charles Pratt dormitory), and Fayerweather Hall were all added to the college grounds. In 1883, East College was removed.

May 1893

As the century drew to a close, it became clear that South was in desperate need of an extensive renovation. Between the years of 1892 and 1893, South Hall underwent a reconstruction. In the Amherst College Archives, there is a notice titled “Rooms in ‘Old South’ Dormitory” dated Sept. 14, 1891. The committee writes, “handsome tiled open fireplaces are retained in most of the rooms,” and that “the floors are of carefully matched hard wood … water has been carried throughout the building, the halls are lighted by gas.” This renovation included adding a “spacious cellar” to add steam heat to the building. Students now had radiators and fireplaces to remain warm in the biting winter months.

1915 to 1920

In 1915 and 1920, “interior renovations and changes” were done. This is quite vague, but it is likely that plumbing was added to the dorm during this time. This would include adding both toilets and baths to the dormitories, luxuries that were only becoming popular at the turn of the century. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1920, only 1 percent of U.S. homes had indoor plumbing, so Amherst was ahead of the curve when it came to amenities.

As you can see from the plan, the first floor has “Toilet Rooms” and the second, third, and fourth floors have “Bath Rooms.” In a conversation with Annie Rubel, director of Historic Preservation at Historic Deerfield, she informed me that the first floor would have been used for going to the bathroom, while the other lavatories would have been filled exclusively with bathtubs. Rubel explained that in the early 1900s, people’s conceptions of privacy were much different than ours now, so the baths would likely not have been separated, rather just arranged in a row.

1933

In 1933, a house library was added to North in memory of Henry A. King, class of 1873. Perhaps out of jealousy, James Turner, class of 1880, decided to donate money for his very own house library in South that same year. Turner had lived in South and felt it only appropriate to donate funds for a library in his old dorm. Along with the cost of construction, Turner donated money for books and art prints for the library. The James Turner Library is on the first floor of South on the north side of the building.

1942

During World War II, Amherst College housed members of the Army Air Corps in South and North Hall. Around 200 soldiers were being trained in the Pre-Meteorology C program in order to gain proficiency in weather forecasting. In “The Consecrated Eminence,” King detailed a conversation he had with the lieutenant of the soldiers where the lieutenant asked for his soldiers to be moved out of South and North because “they [were] too old,” and he did “not like the type of construction.” King responded by telling him if he did not like South and North then the soldiers could sleep in tents on the quad.

One thing that was added by request of the lieutenant was steel fire escapes on the west and east facades of the building. These were added as a safety measure in case the soldiers needed to evacuate the building quickly. Once the men that occupied North and South left, King had the fire escapes removed because he was not fond of the way they looked.

1953

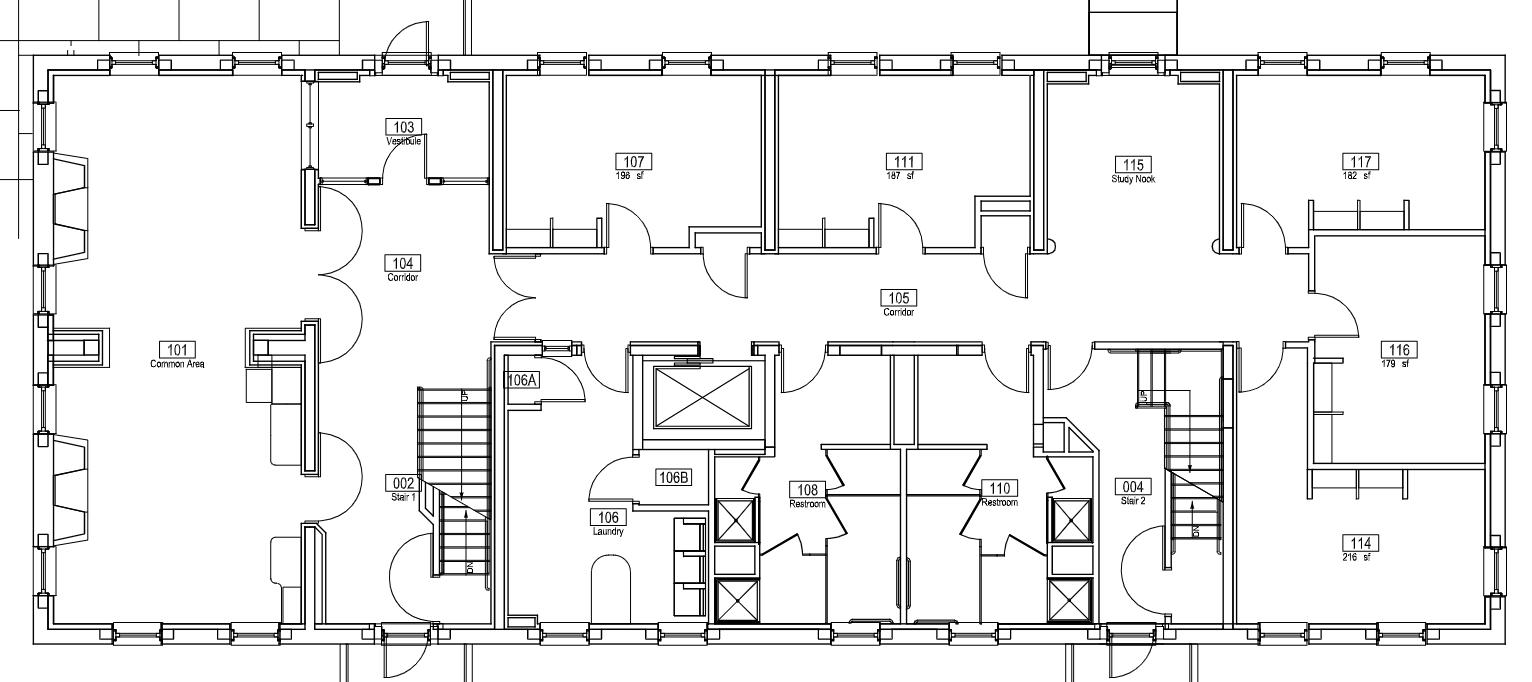

In 1953, South was fully renovated for the second time. This renovation was designed by the architecture firm McKim, Mead, & White, the same company behind other prominent Amherst College buildings, such as Fayerweather Hall. It is likely that the laundry room was added at this time, and steel and concrete were added to reinforce the exterior. The biggest thing that shifted in this renovation was the floorplan. The building’s prior “double staircase” or “entryway plan” became the “double-loaded corridor” plan that it follows today.

Whereas in the first plan there was no central hallway, and only four rooms could be accessed through each door, the current plan features a central corridor with dorm rooms on either side. When South was built, before electricity was around, the “double staircase” plan was practical because the hallway would have had minimal light. Furthermore, a hallway would have taken up valuable space and cost more to include.

In her book, “Living on Campus: An Architectural History of the American Dormitory,” Carla Yanni notes that most women’s colleges at the time, such as Smith College, were almost always built with a “double-loaded corridor” plan. She suggests that these plans allowed for greater security and surveillance, as you could see each room from both ends of the hallway. It is interesting to note this shift in connection with South’s change in plan, because this change is only 20 years before women come to Amherst.

2004

Finally, South received its last update in 2004 with another full remodeling. This renovation was led by Sacco & McKinney architects and was mostly focused on adding common spaces on each floor of the dorm. The elevator and the accessibility ramp on the east side were also added to the building at this time.

Present

In the last 21 years, South has remained largely the same, aside from minor repairs and updates. Over its long tenure, it has housed over 12,000 students, each coming to Amherst to learn, grow, and connect. I began my summer research asking the question: Why is it valuable to understand and inspect past structures? Understanding past structures allows us, through a shared architectural experience, to better empathize with the people of the past. The next time you walk through South, think about the thousands of students who have done exactly the same, and thank the universe that you coexist with indoor plumbing, private showers, and elevators.

Comments ()