State Voting Laws Vary Greatly — So Do Student Voters’ Experiences

With just 20 days until the 2024 presidential election, differences in state voting laws have led to widely varying experiences for student voters on campus — most of whom vote by mail. Some states’ laws enable smooth, straightforward processes, while others’ present major roadblocks.

After Regan Williams ’27 encountered difficulties navigating North Carolina’s complicated absentee ballot system, her mother was forced to hand-deliver the ballot to Amherst on a recent visit — carrying it over 750 miles.

When she at first tried to apply online, Williams found she could only send the ballot to her permanent address in North Carolina, and couldn’t request that it be sent to her college address instead. She attempted to change her address, but it didn’t work.

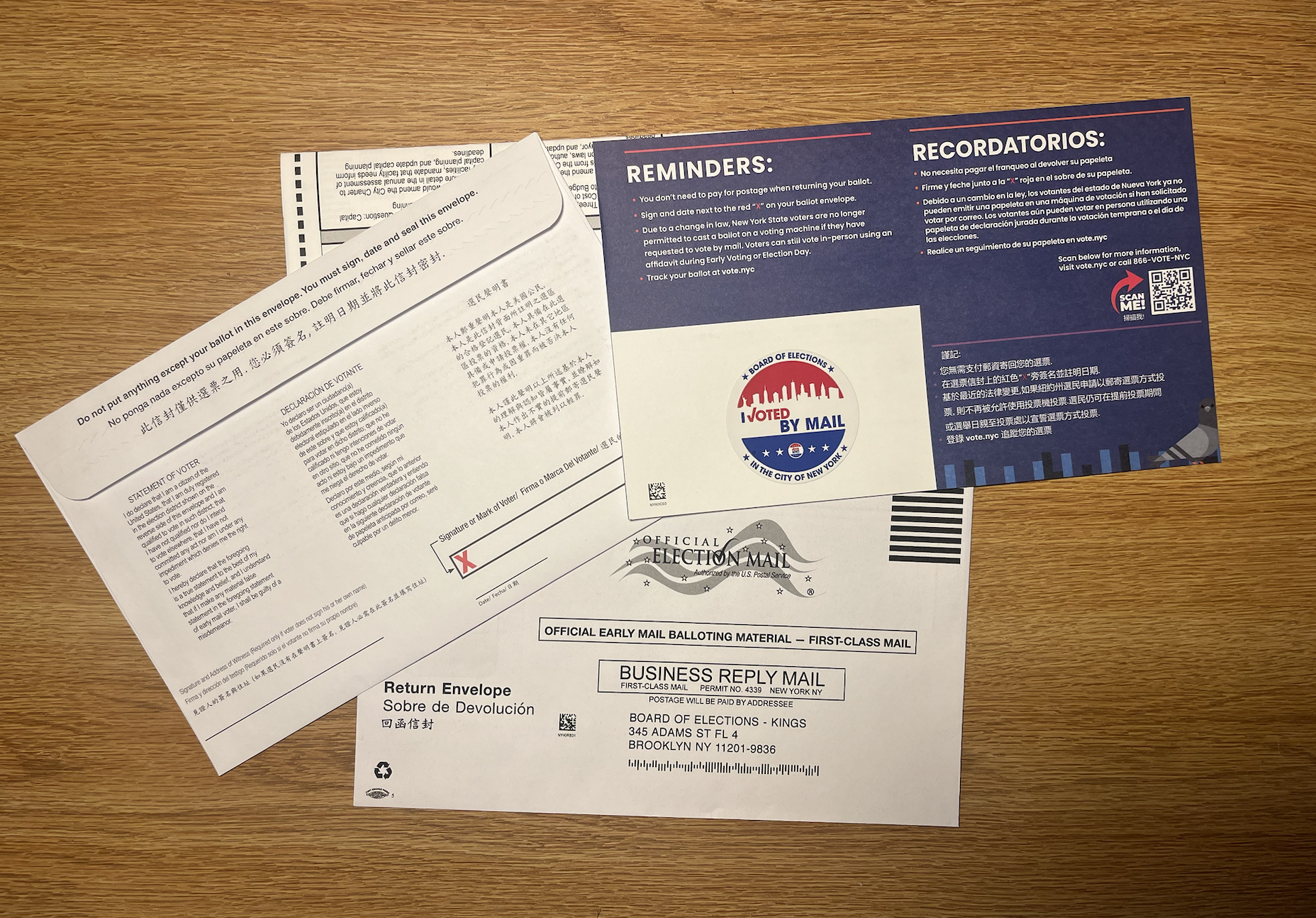

Once her mother brought the ballot to Amherst, Williams photocopied two forms of identification — a driver’s license and a passport — printed them out, and put them in the clear sleeve on the back of the envelope. The state technically required only one form of ID, but she had heard stories of others’ ballots getting rejected, so she wanted to be safe. Two witnesses had to sign the outside of the envelope.

The ballot also came with a number of papers warning of serious penalties for voter fraud if one made any mistakes on the form, which Williams said were “intimidating.”

“They couch a lot of it in preventing voter fraud and protecting your vote … [but] I think honestly, it felt like voter suppression,” Williams said, “Especially with the identification thing … They make it very, very difficult to vote by mail.”

Elsewhere on campus, Mia Sanchez ’26 had a very different, more straightforward experience. Her home state of Colorado is one of eight that already sends mail-in ballots to every registered voter at their home address, regardless of if they request it or not. Sanchez said it was a breeze to request an additional ballot be sent to a different address.

“I requested an absentee ballot just because I didn’t want my parents to have to bother with forwarding it to me,” she said, noting that it came faster than in past years when her parents have mailed it.

With just 20 days until the 2024 presidential election, differences in state voting laws have led to widely varying experiences for student voters on campus — most of whom vote by mail.

Some states have recently imposed new restrictions on absentee voting, which experts say could reduce student voter turnout. Interviews with 15 students from 11 states and Washington, D.C. revealed a range of experiences — from simple and stress-free processes to confusing and complicated ones.

Despite these challenges, all the students we spoke to remain determined to exercise their right to vote.

A changing landscape

Numerous states, particularly ones with Republican-controlled governments, have made voting laws increasingly restrictive since 2020 — often in response to former President Donald Trump’s unsubstantiated claims refuting the 2020 election results.

Experts say many of the most common restrictions could dampen youth voter turnout, which rose to a historic high in 2020 and contributed to President Joe Biden's victory. In that election, held during the pandemic, just under half of all voters aged 18-29 cast their ballots by mail.

Many students are first-time voters with busy schedules and addresses in flux between college and home. That can make them particularly vulnerable to hurdles and confusion posed by new voting legislation, experts say.

Some policies specifically target absentee voting, requiring excuses for ordering a ballot and shortening return windows. Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) reports that these changes to mail-in policies have affected, and will continue to affect youth turnout.

Other laws unrelated to absentee voting have also specifically targeted students. In Ohio and Missouri, for example, new policies dictate that out-of-state students registered at their college addresses may not use an out-of-state license or student ID when they vote — students need to bring a driver’s license from their school’s state or their U.S. passport.

Applying for a ballot

Many students mentioned that they found their states’ online absentee ballot application confusing. After finding the application difficult to complete online, Abigail Robbins ’25 went to her local courthouse in Arkansas over the summer to apply for her absentee ballot.

“If I were to do it online … up here, I think I’d be really confused, and it honestly would have made me wait longer to get registered, or maybe I would have slipped through the cracks,” she said.

Isabel Ibarra ’27, a student from Utah, faced the same challenge as Williams did in North Carolina: she couldn’t apply to get an absentee ballot mailed to Amherst since it wasn’t her primary address. She has since gone through the change of address process multiple times, but her ballot has still not been sent here.

“I went to do it again last week … it’s just not saving or something,” she said, “I’ve never gotten an email … I don’t know anything that’s happening.”

“It’s not surprising to me that it’s so hard to vote by absentee ballot,” Ibarra added, “because Utah has a lot of gerrymandering … But, I still wanted to vote. I deserve to have that right.”

Other students had different experiences. Chris Tun ’25 said that in his home state of Georgia, the form was straightforward, but he pointed out that the state’s requirement that voters print, sign, and rescan the application form could present limitations “for people who don’t have a phone or a printer.”

Ben Tamburri ’27 tried to apply for his Pennsylvania mail-in ballot online over the summer, but the state’s form was down, so he applied by mail instead. “I think I was just too early!” he said.

Aside from that issue, though, Tamburri said the process was “relatively simple.”

“Even when the site was down, I was still able to check online to make sure that my application was received and approved, and my ballot arrived a few days ago.”

Nina Aagard ’26, also from Pennsylvania, mentioned that it was helpful that the state allows people to register for absentee ballots for multiple elections at a time.

Students from Wisconsin, Minnesota, Kentucky, and Washington, D.C. also reported straightforward experiences with the application process.

Denials (and preventing them)

Some students have faced frequent and unexplained denials of their ballot requests. Others have received assistance from their states to ensure that doesn’t happen.

Bela Achaibar ’25, who is from Texas, said that in past elections, the mail-in registration process was confusing and she had her ballot request denied.

“I’ve voted in local elections since I’ve come to college, also absentee. But I’ve had them … returned to sender before, and then I hadn’t gotten it in on time,” she said.

Cynthia Alexander ’26 has had a similar experience in Ohio this year. She sent her ballot request in the mail over the summer, and it was denied for reasons unclear to her. Since then, she re-requested her ballot, but it still hasn’t arrived and she can’t check its status online.

“I’m a little nervous,” Alexander said, “What am I supposed to do? Am I supposed to go home? Because I feel like it’s so important to vote, particularly this year, especially in Ohio.”

Other students, however, received help from their states to ensure their requests were not denied.

Soon after Deb Thayer ’25 filled out their request for a Minnesota mail-in ballot, they received a call from their county.

“They said, ‘Hey, you put the wrong state where you want this mailed,’” Thayer recounted. They had accidentally written Minnesota instead of Massachusetts in their address. “But they checked with me, so they made sure that it was sent to the right address … otherwise I never would have noticed.”

Thayer appreciated the thoughtfulness. “Minnesota’s pretty G when it comes to this stuff,” they said.

Bella Lozier ’26 said that her town in Wisconsin also provided help to ensure ballots themselves weren’t denied.

“When you order an absentee ballot, they also send with it multiple sheets of instructions, the official ones that come with the ballot, but also a printout from the village with instructions like, ‘Don’t use a gel pen,’ and more specific things to make sure that you don’t make a mistake. So that’s really nice,” Lozier said.

Impacts on students

One element that rose above throughout our interviews: time. Students have a limited supply of it, and, depending on the state, the absentee voting process can take up a lot of it.

“It’s super frustrating and super time-consuming,” Williams said. “I think a lot of college people don’t have [time].”

Some states have also become more restrictive about time windows for ballot return, creating additional pressure for students, many of whom reported receiving their ballots close to the submission deadline no matter how early they submitted their requests.

“I think you’ve just got to know when things are due and I think that’s just part of being engaged,” Tun said. But he pointed out that Georgia’s lack of option to request continuous absentee ballots for students once led him to not get his ballot in on time for a runoff election.

“I got it two days before the actual election,” he said.

Aagard mentioned her feeling that while the absentee voting process can work for college students, it is mostly designed for local absentee voters, and it often feels like there is no voting system specifically made for out-of-state college students.

“Think about how many people in each state are going out of state for college, not able to vote in person,” she said, “It feels like people … in college, are an afterthought when election policies are being made … It’s great that we can use it, but it doesn’t feel like it’s built with this situation in mind.”

Some of the difficulties college students experience are significant, like ballots that require permanent address changes for students attending out-of-state schools for a mere four years. But Aagard also brought up smaller issues, like the struggle of fitting a long college mailing address into a small box on a form, or how issues with absentee ballots often require in-person visits.

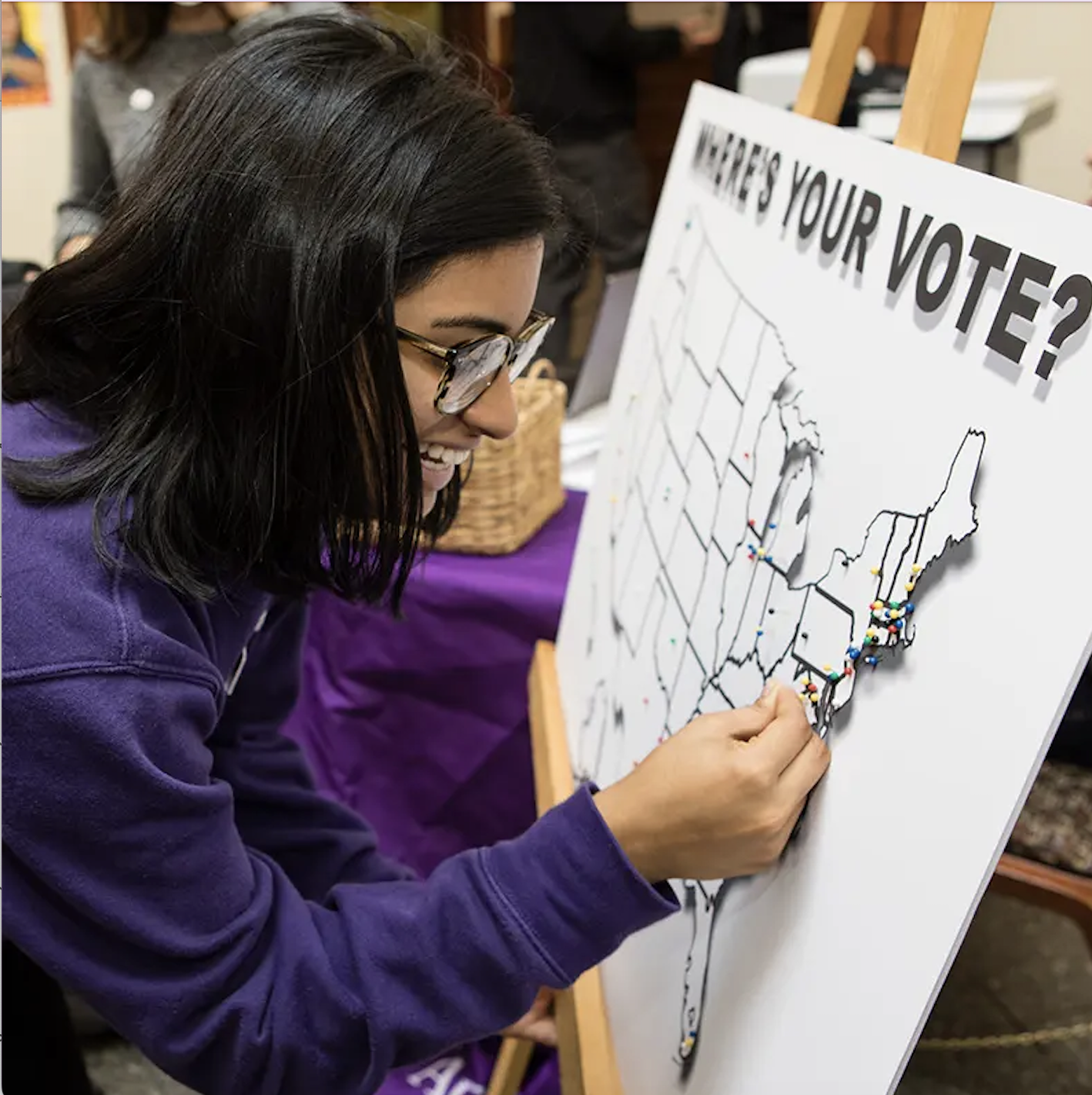

AC Votes, newly under the purview of the Center for Community Engagement, recently sent out personalized emails to each student explaining their state’s absentee voting process. They also continue to provide assistance at their tables throughout campus.

Despite the bumps in the road they’ve faced, students continuously expressed their determination to vote in this year’s pivotal election.

Achaibar, who experienced ballot rejection in the past, has pushed through the hurdles this year.

“I’ve been very much on top of it this year, … logging in [to the elections website] and checking, going to the post office and checking for my ballot,” she said, “It takes a lot of time … [But] I really feel strongly about voting in this election.”

Comments ()