“Stop Making Sense” Suspends Clarity for Sensory Delight

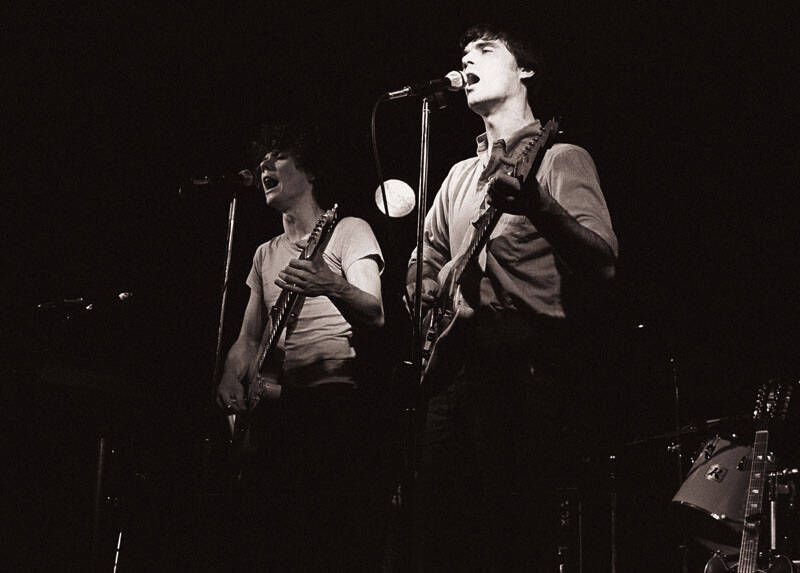

“Stop Making Sense” begins and ends with the image of David Byrne’s lithe, seemingly boneless body writhing according to a mysterious tempo, as it sinuously weaves in and out of a multi-instrumental rhythm by the accomplished members of Talking Heads — whom the concert film follows for four nights at the Pantages Theatre in 1983.

Recently screened at Amherst Cinema, the film opens with the song “Psycho Killer” in which Byrne’s cracking voice hectors and hassles the smooth strings of his weathered acoustic as he moans alienation in the garb of an unsatisfied salaryman. Later, Byrne’s sweaty, slightly crazed visage arrives in the limelight in his trademark oversized business suit, convulsing to the singsong gloom.He sings “Take me to the river / Push me in the water” while looking as if he is demanding a murder fitting to that of a psycho killer.

A viewer is free to recall the title of Byrne’s first song and misapply the thousands of supposed meanings, as the song provokes images of psychotic murders and tries to inflict a semblance of drama or formal intention (on the part of David Byrne, Talking Heads or the director, Jonathan Demme) to reveal the answer to an ambiguous question. To do so is to miss the aimless mark painted by Byrne, Talking Heads or Demme; it wastes the rapturous opportunity to dance as several seniors did in my screening, to sing along to hits gone by and songs newly discovered, to surrender our learned defenses, excuses and suspicions and to, for a precious one-and-a-half hours in the lighted dark, stop making sense.

This is the spectatorship demanded by “Stop Making Sense,” one of the most admired concert films that takes as its subject matter one of the most underrated rock acts. It is the kind of audience that organically emerges after the disappointment of narrative alongside the film’s tremendous reputation. Surely, “Stop Making Sense” does make sense on some secret level, open to the keen and the curious who can, with their sharpened sensibilities, mark the hidden powers that only occasionally leak through the surface to tempt. But one learns — for one has to learn — to accept the bare realities of the film shining in the theater: four nights of 16 pops and bops at Hollywood’s Pantages Theater in December 1983 played live and full of life. The turn the film presents is simple: what seems like an unsophisticated string of cinematically-untouched musical performances becomes one of the most engrossing collective experiences involving the big screen, a feature crucial to this letdown and transcendence of expectation.

Of course, as surely as most simplicities belie more interesting explanations, that initial sense of “untouched” music results from a sophisticated complex of strategic camera placements and allotments of screen time to the various Heads and their instruments.

Demme is smart enough to not push in every time Tina Weymouth proves herself on the bass, perhaps knowing that despite the betrayal of expectation so important to the film, a movie comprised entirely of close-ups of the bassist would be a step too far. The film pretends to assign equal time to each member without evident motivation, sometimes fitting the entire front section of the band as they practice puzzling aerobics in their middle tune “Life During Wartime.” But this casual wandering of the camera can in turn be attributed to the corresponding gaze of the average member of the crowd that stood, cheered and shook at the Pantages; with so much going on, it’s difficult to know where to look.

And no matter where you look, it is all about seeing nothing deeper: Byrne’s own trembling body and singing voice caught in a dancer’s breath overtakes the attention that could have gone to the lyrics, as one thinks about why he does what he does when he does, even as they follow him in step with absolute emotional clarity. It is an aggressive surface the screen emits when this film is playing. There are temptations, of course, to bypass that thin barrier. Among them lie Byrne’s centering in the scene among a significant number of black musicians — he plays a style of music usurped from black creators by white institutions; the aforementioned interplay among the songs themselves; and maybe the elemental drama of seeing lonely Byrne flanked by more and more musicians, who despite their backroom tensions, appear as the most charismatic company of friends.

But the cardinal pleasure of the film, to hear and to see and to perhaps dance, is adamantly set against these readings. It is surprisingly difficult to maintain these analyses during, say, any one of these songs.

To be sure, it is not rare to have films whose pleasures are oblivious to their unpleasant implications, and it is most likely my own bias towards this film that magnifies that pleasure to such a degree as to have myself neglect the possible breakthrough of that enchanting sheen. Perhaps then again, my love of the film’s surfaces doesn’t need to conflict with those who would like to find something beyond the inflicted nonsense. To refer back to the film’s own invisible complexities, one can think of how the film’s aggressive superficiality is another feature of that studied, subtle rendering of the directorial presence, to appear as if to capture what in the moment seems like the greatest happening.

The surface, then, is a forced feature of the film. But forced or not, deceptive or not, intended or not, recognizing the trickery does not undo the film’s magic, another commonality among great films that regardless comes to rare prominence in a rare genre. It still asks you to stop making sense, and you’ll like it. For that, one should search this film and view it on the biggest screen with the biggest crowd. Like the most soothing lullaby, it has been honed with precision: except that lullaby pulls the bed from down under, lands you on your feet and forces you to dream awake.

Comments ()