“Before We Are Scientists, We Are Humans”: Students, Faculty Learn to Navigate Identity in STEM Classrooms

When not teaching introductory chemistry and biochemistry, solving the puzzles of protein folding or checking in with students, Professor of Chemistry Sheila Jaswal, affectionately referred to as Dr. J by her students, strives to become a better human in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). Her efforts coincide with those of the STEM departments at Amherst to diversify majors and faculty hires, where Black and Latinx students, first-generation and/or low-income students and women are often underrepresented.

Near the end of the 2015 fall semester, in the aftermath of Amherst Uprising — a multi-day sit-in in Frost Library aimed at drawing attention to and demanding change of the racism on Amherst’s campus — Jaswal took the time to listen to students in her chemistry class. Students describe Jaswal as “bringing a human side to our classes,” “encouraging” and “Her door’s always open, it really is. She’s so open with all of her students. That’s unique.”

After Uprising, Jaswal issued a Google Form where students expressed feeling impostor syndrome due to their marginalized identities in STEM. Those conversations were the catalyst for creating “Being Human in STEM,” an initiative to make the STEM fields more inclusive for humans of all identities.

In an essay for Diversity & Democracy (a quarterly published by the Association of American Colleges & Universities) Jaswal cited a few specific student responses as bringing into clear focus what was needed to address the concerns voiced through Uprising: “Yes, science is impartial, but before we are scientists, we are humans, and there are systemic changes that the STEM departments can make.”

In the spring 2016 semester, Jaswal and nine students formed the pilot HSTEM (Being Human in STEM) course. They focused on questioning how journeys through STEM can be influenced by identities. The class conducted 40 interviews with Amherst students, faculty and staff and found what they expected: socioeconomic status, race, gender and other identities influence how welcome a student may feel in STEM fields which are dominated by certain populations.

The next semester Megan Lyster, the former assistant director for the Center for Community Engagement and current instructional designer for experiential learning, joined Jaswal to teach the course. Initially, the course didn’t draw crowds — in the 2017 spring semester, only four students were in the class, two of whom had taken it the previous term. But the class remained on the course listings after each semester, and, generally, the course gained popularity.

The project-based class needed leaders from a variety of backgrounds to run the course. For its 2017 fall edition, several instructors joined the team: Science Librarian Kristen Greenland, Pedagogy Fellow Minjee Kim ’17 and Biology Laboratory Coordinator Thea Kristensen. In the spring of 2018, Visiting Assistant Professor of Chemistry Alberto Lopez met the team as well. During the January term, after calls to address racial disparities and anti-Black racism at Amherst had reached a fever pitch in the previous semester through the Integrate Amherst and Reclaim Amherst campaigns, over 60 students enrolled in the course.

The course has not just garnered attention at Amherst. In fact, HSTEM has been offered at Yale, Brown, Pomona, Williams, Davidson and the University of Utah. Other colleges, like Skidmore and Mt. Holyoke, plan to offer the course in the near future too.

Students and HSTEM

During class, students learn through an interdisciplinary lens. They read texts that unify ideas from the humanities and STEM. Additionally, for each cohort of the course, a STEM professor and either a humanities or social sciences professor are paired up. Professor of Latinx and Latin American Studies and Spanish Sony Coráñez Bolton, who taught the course during the January term with Chair of Biology Josef Trapani, William R. Kenan Professor of American Studies and Sociology Leah Schmalzbauer and Jaswal, revealed that this type of model is crucial “the intentional pairing up of a STEM faculty and a faculty member from the humanities or social sciences … models the kinds of interdisciplinary thinking and conversations that we want students to invest in.”

“Human problems are far too complex to be solved by any one discipline,” he said.

The reading material is congruous with the class’s interdisciplinary framework. One section of the course might be dedicated to racism in medicine, while others can focus on Indigenous knowledge systems, representation in STEM or feminism in science. Discussions during class are meant to inspire students to solve problems of equity and inclusion in STEM, whether they’re as local as an experience at Amherst or as broad as a discipline at large — discussions which are not usually held in STEM departments.

Jordan Rhodeman ’21, an aspiring physician who took the course this past January, said that “HSTEM offered a unique culmination of education and experience to reveal the shortcomings in our STEM learning and teaching. The course offered extensive language and vocabulary to articulate a lot of the ideas and feelings we have either previously witnessed or experienced.”

The final project is meant to encapsulate the lessons from the HSTEM course. Past final projects include teaching elementary school students how to extract DNA from strawberries and providing Amherst students information about mental health accommodations. In the first years after the class’s inception, the final projects aimed to cement the learnings of the course and bring concrete changes to the Amherst community.

India Gaume ’22, a biology major on the pre-medicine track, took HSTEM over January term. Though the class ended in late January, she is continuing to work on her final project, and with the help of the biology department, her idea — to create “pods” of students that collaboratively navigate STEM classes — was approved to be implemented this semester in an introductory biology course.

“In HSTEM, I learned that students come to college and want to pursue a STEM field but feel isolated and left behind. The students who feel that way tend to drop out of STEM,” she said.

“The goal of my project is to build a sense of community within introductory STEM courses. If we made everyone feel supported, we would see a decrease in the number of people who drop STEM majors.”

Projects like Gaume’s have been made possible by a trial-and-error evolution of HSTEM, adjusting the course with each iteration. There’s no doubt that the course has changed since its inception in 2015. “The model and structure [of the course] have remained constant, but how those fundamentals take shape has changed over time,” Lyster, who has helped teach the course since 2017, said.

“Each new group of students, and new faculty and staff members who join as facilitators, bring fresh perspectives, and the HSTEM model is designed to celebrate and amplify what each new cohort brings to the course,” she added. “As HSTEM has grown, we’ve needed to develop more structure in order to support more participants, but we’ve worked hard to be mindful of keeping the collaborative process of learning at the heart.”

Lyster highlights the flexible curriculum of the course as a draw for students. “[It’s exciting] to see how HSTEM resonates with so many different types of institutions,” she said. “I think the broad interest in HSTEM is strong evidence of its flexible design and capacity for centering your own local campus community.”

Aidan Park ’22, an alumni of and a Teaching Assistant (TA) for the course, agrees. “I only became a part of the HSTEM family last spring, but I have been increasingly impressed with the influence it has had on the Amherst community,” he said. “It was inspiring to work alongside classmates whose projects went on to make institutional change in the Biology and Chemistry departments in particular.”

He added that as long as there are students with ideas and problems to solve, HSTEM will continue. “Not only do you get to dive into and analyze issues, you are given the opportunity to go and do something about it. Watching students realize what they are capable of is the best part about being a peer facilitator and just being a part of the class in general.”

An HSTEM Approach to Diversifying The Faculty

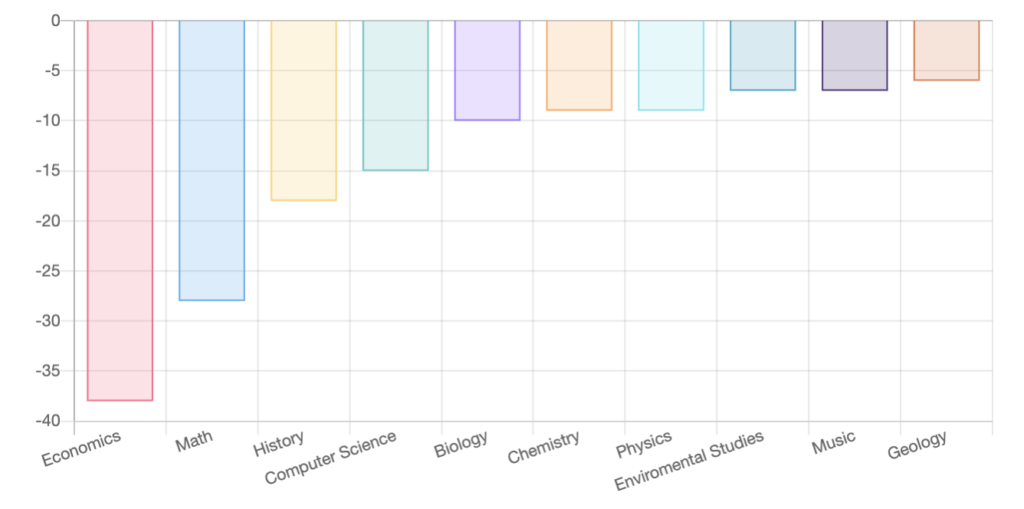

Some of the issues that HSTEM addresses, like a lack of diverse representation in STEM fields, are close to home. A recent report obtained by The Student showed that Black students, among other marginalized groups, are underrepresented in STEM at Amherst.

The same is true of the college’s faculty compared to the student body — a problem which is not to be solved overnight.

The college website reports that 45 percent of students identify as students of color with a 1:1 ratio of women to men (as determined by Institutional Research Data). Looking at smaller subsets amongst majors, however, rates of students of color vary. For instance, environmental studies majors have similar rates of students of color but skew toward having a larger number of women as majors.

In light of shortcomings in hiring practices, science and math departments at Amherst have made efforts to broaden diversity with regard to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, nationality, sexual orientation and religion.

Jill Miller, the chair of the environmental studies department, noted that since 2014 the department has had two hires: Assistant Professors of Environmental Studies Ashwin Ravikumar and Becky Hewitt. The remainder of the faculty were hired into other departments at the college including biology, economics, geology, history, philosophy and sociology.

Miller said that the department makes a concerted effort to promote diversity in its hiring practices. “The diversity of student interests, experiences and backgrounds is one of the strengths of the department and, in a field as interdisciplinary as [environmental studies], engagement with diverse (and divergent) perspectives is really important to a full understanding of issues and also in moving forward with just solutions that work for everyone.”

Similarly, the chemistry department has pursued multiple avenues to diversify its pool of applicants in recent faculty searches. The department advertises positions online in Chemical and Engineering News (the trade journal for the American Chemical Society), at the websites for Academic Careers, the Association for Women in Science, the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers, the Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science and LatinosinHigherEd.com. Additionally, in Sept. 2020, the chemistry department held a “virtual booth,” staffed by chemistry-department faculty, at the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers Virtual Conference.

The chemistry department also emails job-opening announcements to all postdoctoral fellows listed on Diversify Chemistry, a website that describes itself as “highlighting the diverse community of academic chemists” by providing a platform on which chemists can self-identify as members of underrepresented groups.

Anthony Bishop, professor and chair of chemistry, expressed that “implicit bias and systemic racism are still serious problems in the world of chemistry, and that the department is undertaking a number of initiatives to make chemistry at Amherst more inclusive for students, faculty and staff.” He added that department chairs are not provided information about the identities of the faculty or majors in their departments. However, data obtained by The Student indicates that, since 2011, only four percent of graduating chemistry majors identify themselves as Black, a severe underrepresentation compared to the 11 percent of the college population that Black students represent.

The physics and astronomy department is also making efforts to increase representation. Jonathan Friedman, the chair of the department, noted that this task is a challenging one. “A sobering fact is that there are only about five or six Ph.D.s in Physics and Astronomy awarded annually in the U.S. to African Americans,” he remarked. “Our majors are also generally less diverse than the general U.S. population. There are few Black majors. We have seen a significant increase in the number of women majors over the past few years. We are working on increasing representation.” According to data from the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, from graduates of the class of 2011 to the class of 2020, there was only one student who majored in physics that identified as Black, out of a total of 93 majors.

The physics and astronomy department is participating in the American Institute of Physics’s TEAM-UP program that focuses on improving representation and participation of African Americans in Physics; a group from the department recently attended the first TEAM-UP workshop. In addition, the department is working with the National Society of Black Physicists about ways to highlight early-career Black physicists and astronomers.

The computer science major faces similar difficulties in representation. “Computer science, as a field, has had among the least diverse demographics — on gender and race — of any field,” Scott Kaplan, professor and chair of the computer science department, said. [Only five percent of computer science majors in the past ten years identified as Black.]

“We are constantly discussing how to attract a representative group of students into our classes, and how to retain them for the major,” Kaplan added. “In hiring, we put forth similar efforts with help and encouragement from the administration. Racial diversity, in particular, is difficult to achieve when hiring faculty, simply because the number of racially diverse candidates is so small nationally.”

Change Beyond Amherst

The key to overcoming persistent barriers in STEM representation are movements and education like HSTEM. Such courses empower students to address diversity in STEM and also to feel connected with their classmates. Ji Chung ’22, a former student in the Spring 2020 edition of the HSTEM class and a TA of the January term course, noted that the work of the HSTEM class is invaluable. “The HSTEM class gives me an opportunity to feel like I am part of the cohesive and evolving community. We call ourselves a family, and that really is accurate. Our network is the key to bringing a more human perspective to STEM,” she said.

Rhodeman also elucidated that the communal aspect of HSTEM provides an impetus for change. “Amherst boasts an open curriculum, but this was the first time I truly felt an open space in a class to be vulnerable and engage in meaningful and difficult dialogue because everyone really wanted to be there,” she asserted.

Started amid national turmoil following protests at the University of Missouri, Yale and Amherst, HSTEM stood out as a way to change the culture of STEM education. It appears to be working: it’s currently offered at half a dozen colleges and universities. The HSTEM course was awarded an National Science Foundation i-USE grant — money which is reserved for improving undergraduate STEM education — to hold the first national Being Human in Stem conference to take place in June 2021. HSTEM previously held annual regional summits with Yale and Brown.

“I have learned not only about the human experience in STEM, but lifetime skills in listening, communicating and reflecting,”

— Jordan Rhodeman

“I have learned not only about the human experience in STEM, but lifetime skills in listening, communicating and reflecting,” Rhodeman said. “I have learned that these skills make it possible for a diverse community to come together to create lasting systemic change.”

Comments ()