The Day Bip Roberts Cried: Notes on the Athletics’ Last Game in Oakland

The Oakland A’s played their last game in California on Sept. 29. Staff writer Toby Rosewater ’28 reflects on the team’s legacy and history as they move on to Las Vegas.

Bip Roberts played professional baseball for 17 years, appeared in 1,810 games, and stepped to the plate 7,130 times. In all those appearances, there’s not one moment, one baseball card, one snapshot, or one video of him breaking down. On Thursday night, a retired Roberts sat in the quiet, air-conditioned halls of an NBC Sports California studio. There, his post-game co-host, Brodie Brazil, asked him a simple question.

“You’re a baseball guy. I should be asking you about double-plays and hitters going the opposite way, but [you’re] also [a] Bay Area [person] born and raised in the East Bay…What’s your initial takeaway with just how today played out?”

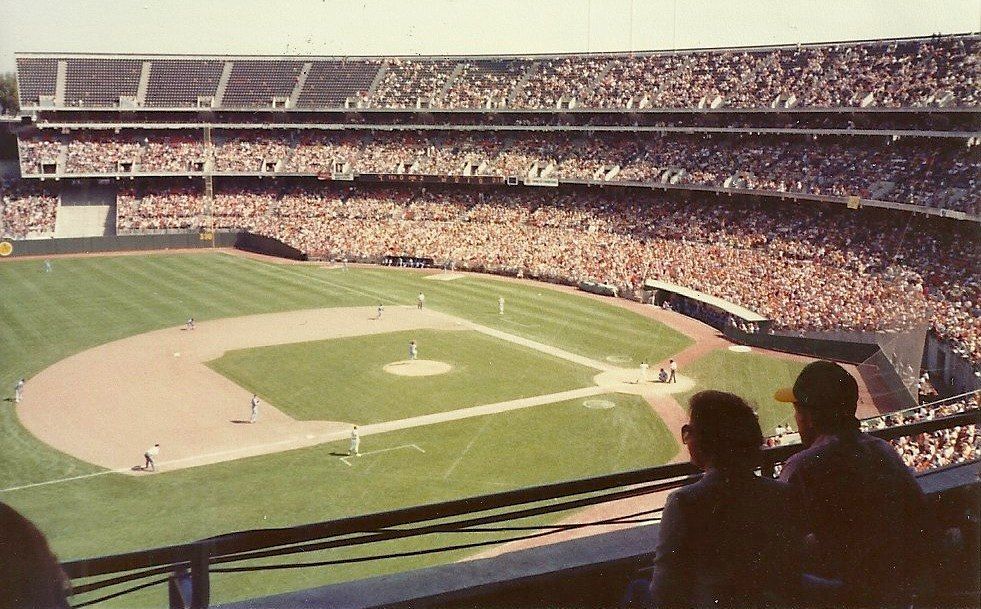

Before Brazil finished his question, Roberts gently extended his arm to the tissue box sitting center table. In that moment, he had no words. There was no home run he could hit to change the situation’s reality, no base he could steal to alter its outcome. The Oakland A’s had played their last game in California on Sept. 29 — their last of 4,454 games played at the Oakland Coliseum. As a Bay Area guy who covers the team, Roberts could only cry.

A pro sports team is like a language. There’s the language itself: its words, syllables, verbs, nouns, conjugations, declensions, and so on. Then there’s its wealth of knowledge — its insulated nest of culture, stories, geography, art, and local history. When a language dies, as linguist Ken Hale writes, “It’s like dropping a bomb on a museum, the Louvre.” A baseball club isn’t all that different. There’s the nine players on the field, the pitcher, the hitter, the bat, and, of course, the ball. Then there’s its wealth of knowledge — its repository of history — a collective consciousness filled with numbers, places, people, and wonder. From this, memories manifest as throwback uniforms, honorary bobbleheads, and fragments of renowned or forgotten memorabilia.

The A’s have existed for 123 years. The club has moved three times in its history: first from Philadelphia, then from Kansas City, and now, come season’s end, from Oakland. My grandfather, a Philadelphia native, still remembers the team’s time in the city. My dad occasionally gifts him items evocative of the team’s time there: an old t-shirt, a pennant, a Mitchell & Ness jersey, and so on. In that sense, Philadelphia’s repository hasn’t dissolved; it’s just finished collecting memories. As long as the Athletics exist in some fashion, the consciousness of the Philadelphia A’s will continue to sit on a shelf, gathering dust. It’s a privilege a truly dead language does not have, as no dying tongue has a 1.2 billion dollar evaluation to guard its intellectual wealth.

Because of that, as the A’s prepare to move to Las Vegas in the coming years, Oakland will join Philadelphia on that old dusty shelf. They won’t be forgotten either; Bip Roberts certainly won’t forget them, and neither will Clay Wood, a groundskeeper of 31 years who broke down as he left the field for a final time. Remembered or not, it still stings; Oakland fans will have no one to cheer for — no pro game in their backyard. As a writer, I can relate in a way; I spend all this time staring at my screen, reading lines of my own speech, rewriting and rewriting. As long as I edit, add, and change, my story is alive and unfolding, but when I’m done, truly done, it’s over — dead. If I think about it too much, it fills me with this real deep sense of despair, a kind of aimlessness. As the A’s move on and their Oakland chapter ends, part of me wonders if their fans feel the same.

Still, there’s beauty within this end. Baseball, and sports for that matter, have a knack for the definitive ending: an old Ken Griffey Jr.’s last at-bat, a prime Joe Carter’s World Series walk-off, etc. Both these men, at wildly different points in their careers, got to experience a definitive end. In real life, most things don’t conclude this way — this pretty, this certain, or this idyllic. Some things end unexpectedly, in a plume of fiery smoke or in a lonely emergency room. Others languish; the Titanic sank more than 100 years ago, and since its rediscovery in the 1980s, it seemingly hasn’t had a single moment of peace. It will be visited, and talked about, and recreated in some form until it is nothing more than a rusty streak on the ocean floor.

Conversely, some things end in an instant. When a stadium reaches the end of its life span, it is often imploded. The whole thing comes down simultaneously in a controlled, engineered blast. In just a few seconds, what once was a theater of artistic and athletic achievement is reduced to a dilapidated pile of gray rubble. This is, in all likelihood, the fate of the Oakland Coliseum. It’s a jarring realization — the reality that something so colossal can be and then, seconds later, not be.

There are worse endings, though. For instance, companies normally send retired cruise ships as large as the Coliseum to one of a few major scrapping facilities in Turkey, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. The ship sits there, docked beside other fancy vessels, as underpaid and overworked shipbreakers risk their lives to dismantle the ship in a process that takes up to a year. If that’s not an all-around horrible, genuinely inhumane way to go out, I don’t know what is.

You see, a lot of things don’t end pleasantly, whether it be a human life, a ship, a building, or an object. Even our beloved Amherst College, with its sparkly 3.3 billion dollar endowment, will, at some point, in all likelihood, hold its final class. With a sold-out crowd in attendance on Thursday night, the Oakland A’s got their turn to end. Yes, it was sad, and melancholy, and confusing, and heartbreaking. But it was also idyllic — a definitive end — and a moment of reflection. The players raised their caps to the home crowd one final time, looking around as they soaked in the stadium’s sincere emotional soup. Part of me believes it’s the moment’s fleeting reality, its finality, that makes it feel special. Some will be an A next year, others won’t. But none will be in that moment, in that stadium, on that grass, with those fans, ever again.

Comments ()