Film Society x The Student: “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar”

In the second installment of Film Society’s column, Diego Duckenfield-Lopez ’24 admires the metatextuality of Wes Anderson’s new short film, “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar.”

“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar,” released on Netflix on Wednesday, Sept. 20, is part of Wes Anderson’s latest directorial effort: a collection of short film adaptations of Roald Dahl stories.

It’s a feast for Wes Anderson fans, to say the least, and it also marks Anderson’s first return to the author whose novel inspired the iconic stop-motion animation film “Fantastic Mr. Fox” (2009). Anderson’s new collection arrives not long after his latest feature film, “Asteroid City,” which saw Anderson at his most metatextual. He continues this trend with “Henry Sugar,” a unique adaptation in which actors recite Dahl’s original prose as dialogue.

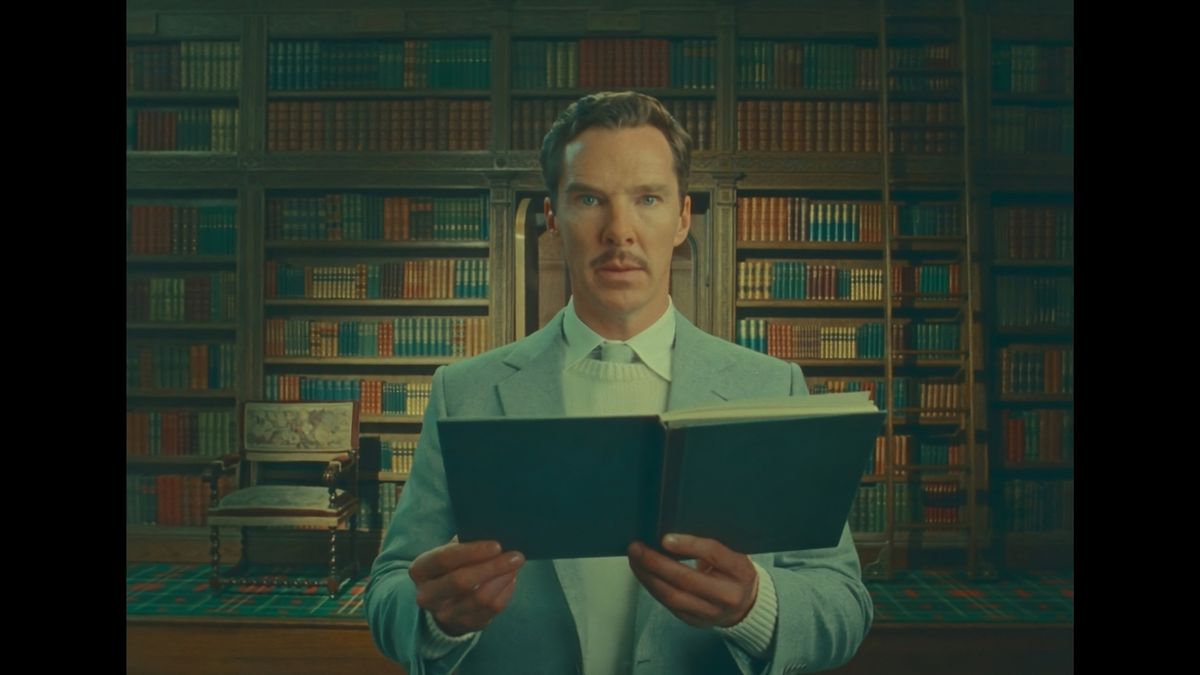

“Henry Sugar” reunites Anderson with Ralph Fiennes, who starred in “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” and includes Anderson newcomers Benedict Cumberbatch, Dev Patel, Richard Ayoade, and Ben Kingsley. Cumberbatch, who plays the protagonist, is a natural fit for Anderson and it is hard to imagine that he is new to Anderson’s rotating ensemble. The actors deliver their lines at a lightning pace and directly address the camera, breaking the fourth wall for a majority of the film. It is a schtick that would grow tiresome in a feature length film but does not overstay its welcome in the shorter format.

Anderson seems destined to carry the whimsical nature of Dahl’s stories onto the screen. His dollhouse-like sets recall a child recreating the story in their playroom. This playfulness has always been a staple of Anderson’s style, but it is especially suited for children’s stories like “Fantastic Mr. Fox.” Nonetheless, the story’s ostensibly juvenile plot does not prevent Anderson from conveying a heartwarming and complex tale of spiritual growth.

Nonetheless, the uplifting plot is limited by Anderson’s unfortunate use of orientalist tropes and aesthetics. Critics have noted in the past that films like “The Darjeeling Limited” and “Isle of Dogs” reduce Asian countries to backdrops for white characters’ journeys of personal growth. Although one can argue that “Henry Sugar” condemns the protagonist’s exploitation of Hindu religious practices, the adaptation is too faithful to suggest that Anderson intended to critique the original story’s problematic orientalism.

However, the much more interesting part of the film is its exploration of the filmmaking process. Like “Asteroid City,” in which much of the film occurs within a live production of a play in a fictional TV program, “Henry Sugar” embraces recursive storytelling. The film starts off with Roald Dahl (Ralph Fiennes) writing the titular story, then quickly transitions to the story’s protagonist narrating his own actions in Dahl’s prose.

Soon after, Henry Sugar begins reading a doctor’s written recollection of when he met a man who could see without his eyes and then we hear the rest of the story retold by the doctor himself, played by Dev Patel. Each character narrates their own story within the film. “Henry Sugar” feels like hearing a bedtime story read aloud with moving images replacing the illustrations. And of course, being directed by Wes Anderson, there is no shortage of visual flair.

Anderson, who built his career upon hyper-stylized visual language, takes his aesthetics to the next level in this film. Anderson heightens the film’s artificiality by changing the actors’ wardrobes and makeup in the middle of shots as they narrate their backstories. He also occasionally slides away mattes (painted backgrounds) to reveal sets that look like three-dimensional renderings of the matte.

Throughout the entire forty-minute runtime, Anderson insists that the audience remain aware of all the elements that make up the film. Although Anderson has always prioritized each shot’s intentionality, his attention to artifice in “Henry Sugar” perfectly matches a screenplay that consistently reminds the viewer of its source material.

In the lead up to “Asteroid City,” social media users started a trend to depict their own lives in the style of Wes Anderson. These videos often reduce Anderson’s style to muted colors, symmetry, and deadpan faces. Yet, Anderson continues to prove that he is more than an aestheticist and that his distinct style is an essential part of the films themselves. “Asteroid City” felt like the natural culmination of Anderson’s formalism through its exploration of the artificiality of acting as well as its ability to express genuine emotions. Although “Henry Sugar” may not reach the emotional heights of “Asteroid City,” the short surpasses the feature film with its metatextuality and the endearing simplicity of Dahl’s tale.

Comments ()