Thoughts on Theses: EJ Collins

EJ Collins is a Black studies and education studies double major. His thesis focuses on how North Carolinian independent schools served as spaces for liberatory education, how the state restricted those efforts in the ’80s, and the lasting impacts of those restrictions.

Q: What is your thesis about?

A: My thesis is looking at independent schools and how they served as liberatory spaces in North Carolina going into the ’80s. North Carolina is a state that had integration practices that were similar to Mississippi and Alabama, and what’s really interesting is how they shifted their model of education to be somewhat more progressive, but in the midst of that, it still became inequitable for Black and brown communities. I went to the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics [NCSSM], which was an effort that was created by the state in 1978. Being right down the street from Duke University, as well as Malcolm X Liberation University, [which] shut down in 1973, that was the tension that sort of brought me to this topic, because I was like, ‘We have a tradition of Black radical education and just the general radical education, and it’s sort of been covered up in history.’ And so this thesis is basically looking at the the inner workings of how it was covered up, [and] how the state basically co-opted these forms of independent education in order to still push the agenda for discriminating against certain communities in the state.

Q: How does it feel to write a thesis so rooted in where you come from?

A: It’s very healing. Growing up, I went to a total of 10 schools. I’ve been to charter schools — actually, one charter school — and I’ve been to public schools within … Mecklenburg County, which has had a history of redlining and resegregation. And so it’s very healing for me to not only discover the workings of the state to cover up this history, as well as [covering up] efforts towards community-based education, but also to see how — because NCSSM is the first public boarding school ever made — how this was a wave that occurred in the South within the decade that followed. And so it’s applicable to not just North Carolinian education, but really the whole southern education system. So it’s a very healing process, as well as very enlightening. And to be able to talk about this, as well as collaborate with people who’ve been to these types of schools, and also just, you know, all of us have been exposed to education in some way, shape or form. It’s been such a connecting experience.

Q: I want to hear more about that connective experience. You said you’ve talked to other people who attended this kind of school?

A: I have a couple of friends such as Fareeda Adejumo [’23], who attended the Alabama version of the school, and Gracie Rowland [’25], [who] attended the Mississippi version. And then a couple of students from the same school that I went to. Just being able to discuss not just the structure of the school, but how these schools are, when it comes to first-gen[eration] and low-income students, very inequitable, even on these campuses and even for the small population that are on these campuses, … the school really doesn’t show support for them, as well as just U.S. students across the states as well. I mean, we’ve all made it here, which is, you know, a good thing. But also to be able to connect with friends and acquaintances that are very much acclimated to these forms of education has been a fun experience, you know, kiki-ing about residential life or what have you. But also to just talk to my friends who have been exposed to just a wide range of educational experiences. It’s been very, very fun, as well as community-building.

Q: Did you feel like you learned about this topic in high school? Or was it something that you dove into at Amherst?

A: It’s definitely something I dove into at Amherst. I took a course with Professor [of Black Studies and History] Hilary Moss called “Race and Educational Opportunity in America.” And it just opened my eyes to the larger impact. Of course, from my individual experience, I’ve had experiences with my race, as well as queerness, in these spaces, but to see how this effort on a national level ever since Brown v. Board of Education ultimately was still ineffective in establishing equity. Sorry, that didn’t really answer the question. Basically, I didn’t learn about this before coming here. Because the schools [I went to] are geared towards science and mathematics, I came here with a very heavy science mindset. And then being able to take that course opened my eyes up to ‘Wow, okay, so this is the direction of these state-led efforts and how they are more geared towards getting students in the market, rather than actually having them learn about their history and learning about how they can get involved in their community and combating discriminatory practices.’

Q: Do you think it’s made you look back on your educational experience in a different way?

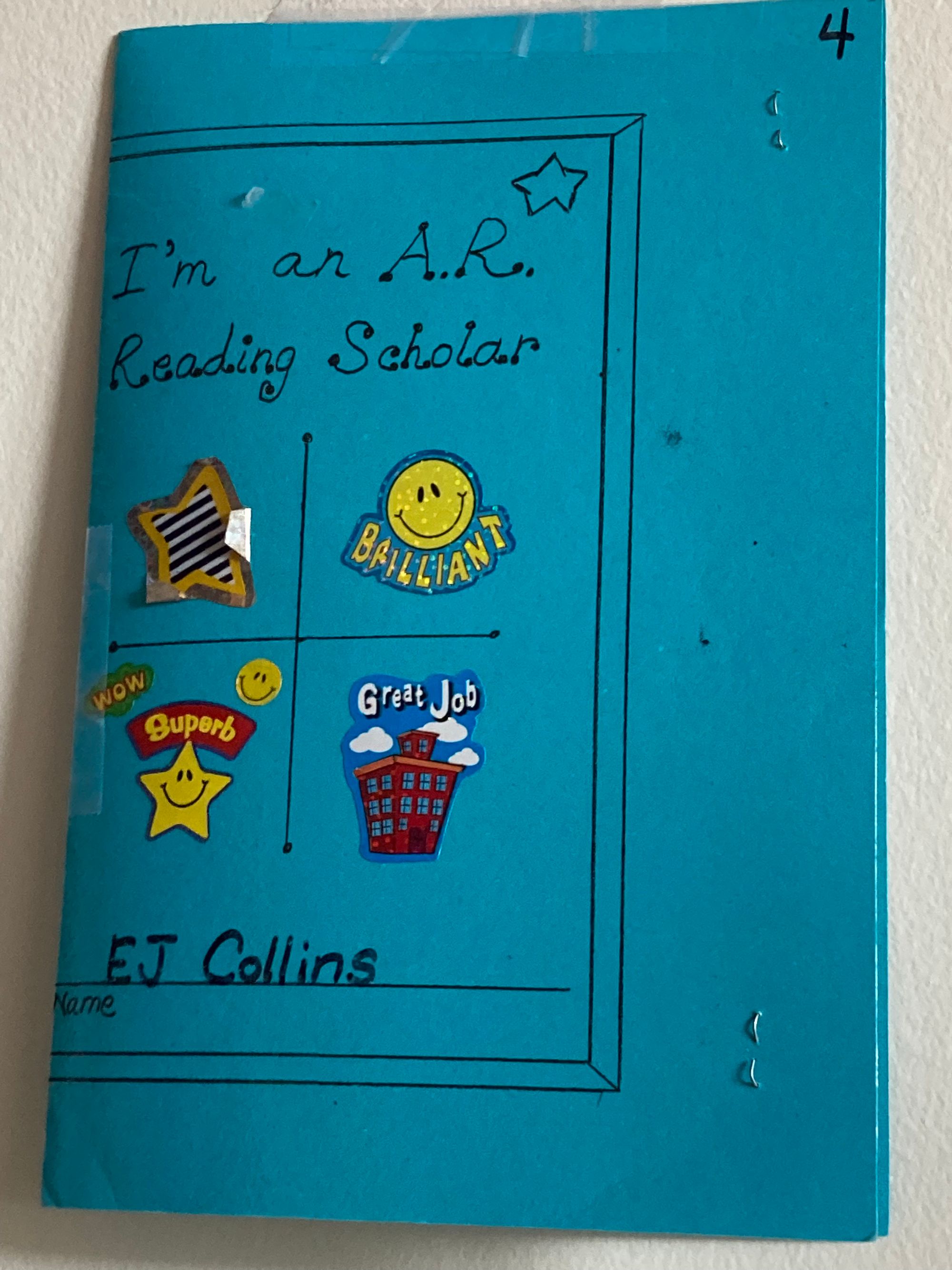

A: Absolutely. My mother was very much involved in my educational experience and at different schools I experienced different types of practices. And my mother always wanted the best education for me, even in the midst of our socioeconomic circumstances. And so it is definitely — going back through all six elementary schools, two middle schools and two high schools — a lot for me to look at each type of education in a different way. Whether it’s, you know, the inequitable practices of a talent development program in a public school, or how different practices within the school systems only reestablish the school-to-prison pipeline in very apparent ways and even sometimes disappearing ways. But it’s definitely caused me to look back at my experiences. I currently have a book on my wall, actually — sorry, this is not show and tell, but … [Collins holds up book from his room]. So this is from third grade. And I know they don’t really do these practices anymore. So [this is the] Accelerated Reader test, and I used to love reading before going into the third grade. … But what they did is they had us read these texts, but then next to them, you see all of these percentages, they would have us take tests on these books. And so it wasn’t really like we were reading these books to, you know, have a discussion or to see how they link to contemporary times. And this for the longest time had me convinced that I wasn’t necessarily capable of reading or interacting with reading. And so, like I said, it’s been a healing process. But I want to make sure these practices … come to a close, but also [that] the history of these practices are exposed. So people don’t have to be exposed to these types of discriminatory practices.

Q: How did Amherst influence the direction of your thesis? I’m especially curious about the intersection of Black studies and education studies.

A: Coming to Amherst, I wasn’t really 100 percent sure on what to expect — going to NCSSM is a high intensity environment, very competitive. Students before going into the SAT would be like ‘I don’t understand why I have to take this test; I got a 1580 on the test.’ And so a lot of the time students there were very, very competitive. And coming here, it’s more of a community-based experience, which I think me and a ton of other students — because we all come from relatively competitive backgrounds — haven’t necessarily been exposed to. And so [seeing] how private forms of education in grade schools, but also at the collegiate level, to see how these forms of education came to develop and came to be and how they were shaped, really sparked my interest. I was a chemistry major/biochemistry major, and during Covid, especially during the Zoom semester, I was like, ‘Okay, this is a really interesting time in education, we’re not in the lab, students across the nation are on Zoom. Some students don’t even have the opportunity to have technology. Parents are trying to figure out how to balance their economic circumstances, as well as taking care of their children.’ And so it was just a very pivotal time for education. I thought, ‘Wow, all of these practices have led to this moment where so many people are questioning: What is education for?’ We just discussed this in [Lewis-Sebring Visiting] Professor [of Education Studies Kristen] Luschen’s class “Politics of Education.” And so to have these experiences, and these conversations at the school has really been eye-opening, and even influential in deciding the path that I’d want to embark upon.

Q: That segues perfectly into my next question, which is: What impact do you hope your thesis will have?

A: I hope that this research not only exposes or brings to light the history of these traditions, but also serves as a stepping stone for people to be able to look back at their history in their state of education and be like, ‘Oh, this is why I’m looking at a school that was constructed in a hospital that opened in 1898.’ Right? And to see, ‘Oh, okay, my school doesn’t get this much funding, because testing scores are this low.’ And so they will be able to apply it not just to their own students or kids when they grow up, but to see the different ways that we can collectively come together to come to a more liberatory form of education and come to a form of education that isn’t necessarily geared towards the job market or geared towards getting people … into positions that further push these these discriminatory practices.

Q: And do you want to continue with this work after your thesis?

A: Yes, hopefully! I am currently applying to Ph.D. programs. Through the Mellon Mays undergraduate fellowship, I was able to start this research ahead of time, as well as get a little head start as far as observing the process of applying to Ph.D. programs [while working on] the thesis. So I am hoping to go to grad school after this for Black studies, or Africana studies, or African American studies in order to do more research on how education and Black studies are inherently linked together, because a lot of the practices and the systems that have been formed to [distract us from] what the plight has been for us, as well as the impacts of capitalism ever since emancipation onwards. And so I’m very, very excited for, hopefully, grad school.

Q: Is there anything else you’d like to add, or make sure people hear?

A: Just a really large thank you, not just to The Student, because thank you so much, but also, [to] my advisors [Alfred Sargent Lee ’41 and Mary Farley Ames Lee Professor of Black Studies Olufemi Vaughan, Charles Hamilton Houston ’15 Professor of Black Studies and History Stefan Bradley, and Lewis-Sebring Visiting Professor of Education Studies Kristen Luschen], as well as the Mellon Mays program, and the Black Students Union. And just all of the community efforts that I’ve been involved with on campus and the efforts that I’m getting involved with off campus such as the Black Alliance for Peace. And I’m thinking about how to incorporate this outside of the classroom, and thinking about thanking the communities within and outside of the institution in order to further the collective cause.

Comments ()