Visiting Scholar Sven Speiker Argues for “Art as Demonstration”

Professor Sven Speiker visited the Amherst Center for Russian Culture last Thursday to discuss his new book, “Art as Demonstration: A Revolutionary Recasting of Knowledge.” Staff Writer Nichole Fernandez ’25 discusses the lecture on radical Communist art of the 1960s.

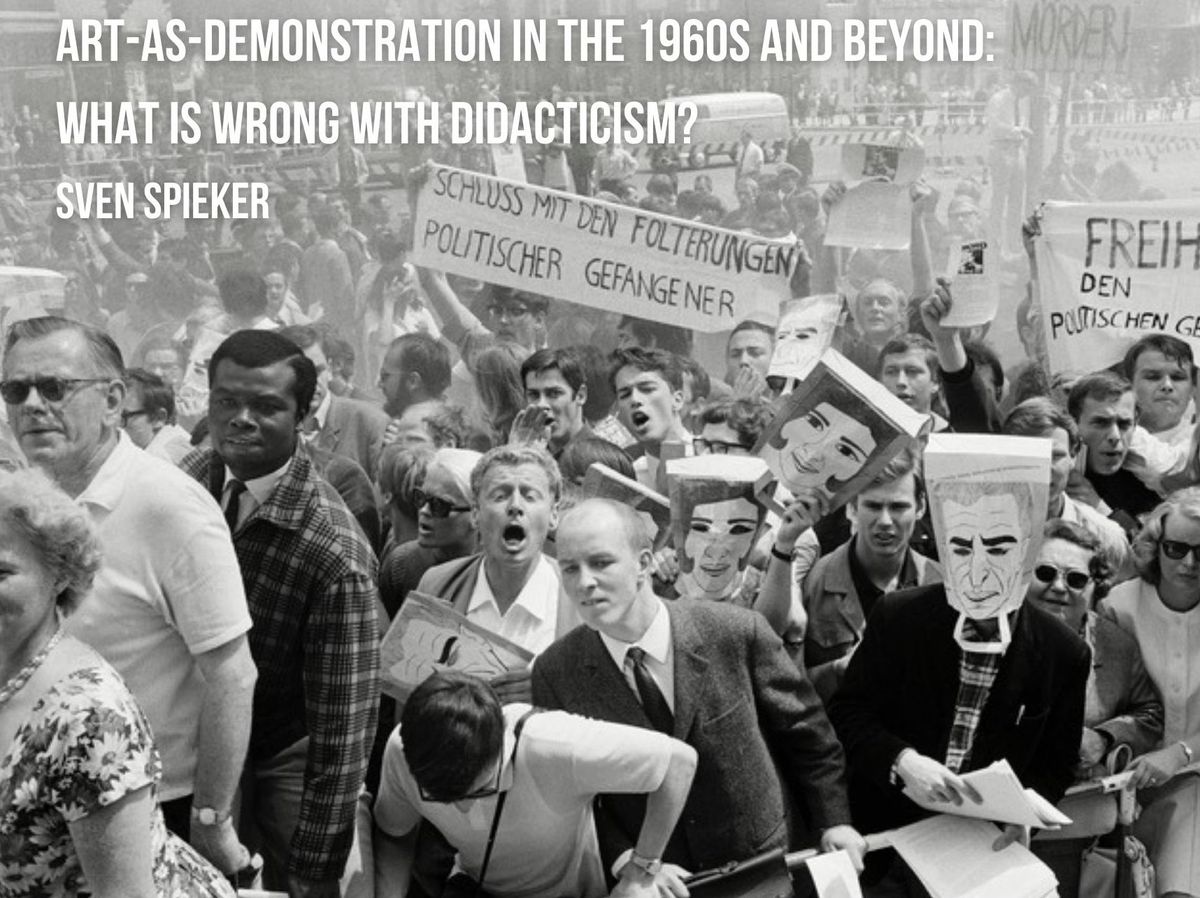

The Center for Russian Culture welcomed Sven Speiker on Thursday, Oct. 12 to present his research on radical Eastern European and German art of the 1960s as demonstrations, or gestures of pointing towards a social condition beyond the work itself. Speiker is a professor of history of art and architecture, comparative literature, and Germanic and Slavic studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he specializes in critical theories of modern and contemporary art. His lecture provided a distillation of his forthcoming book, “Art as Demonstration: A Revolutionary Recasting of Knowledge.”

In his lecture, Speiker focused on demonstration as the foundation of Eastern European contemporary art of the 1960s, a period he defined as dating from the mid-1950s to mid-1970s. Looking at Marcel Duchamp’s “Unhappy Readymade,” for example, Speiker expanded the concept of demonstration, which we often visualize as marches, sit-ins, and picket signs, to encompass a broader range of techniques artists and activists use to motion towards something larger than the gesture itself. Speiker presented “Unhappy Readymade,” a geometry book left to deteriorate outside a window by Duchamp’s sister, as a work exemplifying demonstration in its simplest form: the pure gesture of pointing. Terrorism, then, is demonstration in its most extreme form, typically pointing to the extent of a state’s brutality by provoking retaliation.

According to Speiker, the “discursive impasse” of being a Marxist artist producing transgressive work within a leftist regime is what differentiates the political contexts of 1960s Eastern European art from its Western European counterparts. Speiker argued that the absurd instructions of Czech performance artist and activist Milan Knížák’s “Demonstration of One” show how leftist artists find ways to surpass this “impasse” and disrupt leftist states. In the writing that accompanied his demonstrative performances, Knížák instructs, “Stand still in a crowd, unfold a piece of paper, stand on it, take off your ordinary clothes and put on something unusual.” Through this disruptive behavior, Eastern European artists developed what Speiker calls “their own alternative truth procedures,” creating and transforming an alternative proletariat sphere.

What I found most resonant in Speiker’s lecture was his articulation of how the didactic nature of a work of art, being the work’s act of pointing towards something within its wider context, may not always make itself clear until it has been archived. Speiker describes this phenomenon as a character of “belatedness.” Tamas Szentjoby’s demonstration, titled “Sit Out. Be Forbidden,” in which he sat gagged outside of the Intercontinental Hotel in Budapest, was shut down by police who accused him ofengaging in anti-Communist action. His demonstration most likely heldno discernible meaning to passersby. However, after the piece was contextualized in the archival process, it revealed itself as an act of solidarity with Black Panther leader Bobby Seale. Speiker argued that belatedness operates “much like traumatic symptoms point like a diagram in the direction of an accident that cannot recall or represent.”

Speiker articulated a process familiar to activists, artists, and academics who anchor themselves and their practices in histories of trauma and oppression: retroactively looking at the archive, oral history, or memory helps construct the present public sphere. Didactic, transgressive art points not only to the cultural and political context of its production, but to alternative ways of being and pathways for people to resist their own oppressive conditions through art. In other words, they can be tutorials in “taking off our ordinary clothes.”

Comments ()