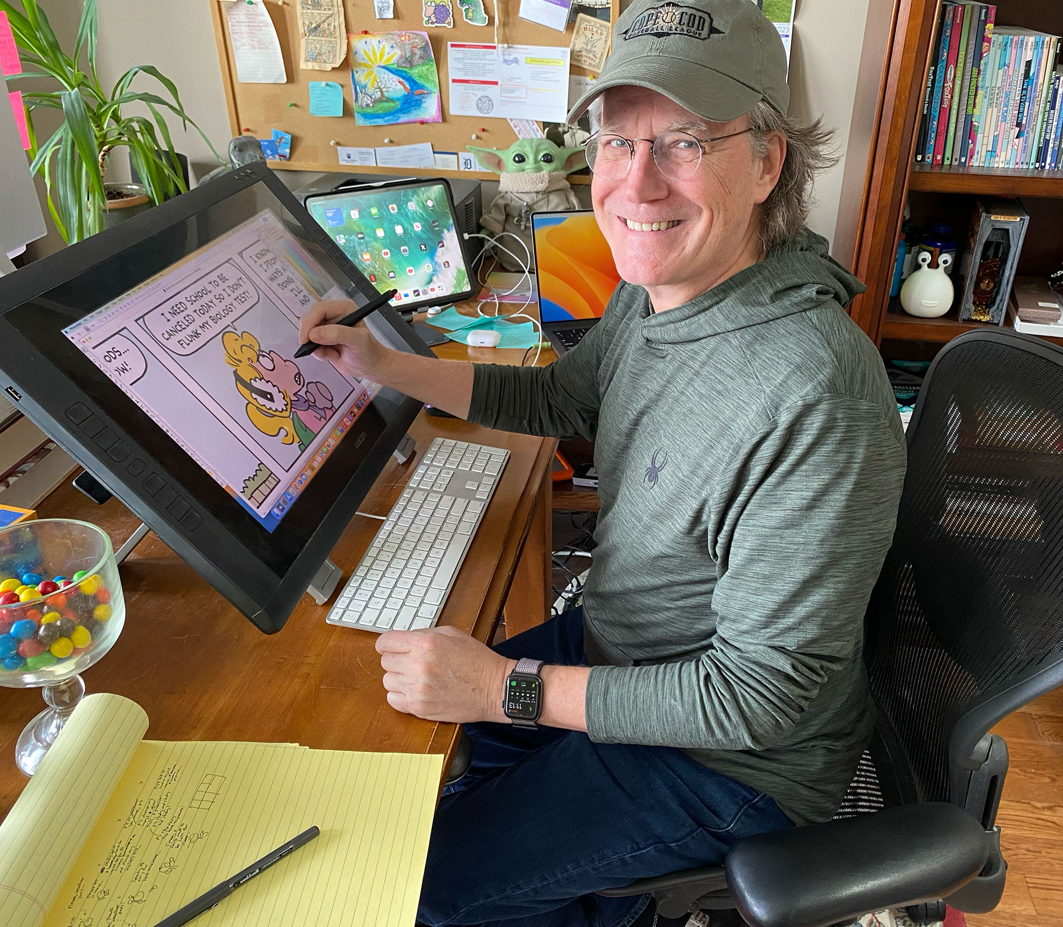

A Cleanly-Drawn Career: The Mind Behind “FoxTrot” — Alumni Profile, Bill Amend III ’84

From The Amherst Student newsroom, through the past 30 years (and counting) of “FoxTrot,” Bill Amend ’84 has made a life out of nerdy humor and creativity.

A suburban American family with three kids. Geeky references to pop culture. Math and science jokes. Punchy, sardonic humor. A simple and clean art style. If you find yourself noting all of these characteristics, it’s possible you’re reading “FoxTrot,” a weekly Sunday comic strip created by Amherst alum Bill Amend ’84.

Today, Amend is a successful creator in a competitive industry. He had a goal, and he also had the courage and the work ethic to pursue it. But when he began making small animations and cartoons for fun in high school, no one could have guessed that his comic would appear in more than a thousand different newspapers and be compiled into 44 collections and anthologies. It’s been “kind of crazy,” he said.

Cartooning in College

Amend applied to only three colleges, and he applied to Amherst mainly because his father had also gone there. He describes his acceptance to Amherst as “miraculous,” speculating that he was probably one of the last to be chosen.

Originally, he had wanted to be a filmmaker akin to George Lucas or Steven Spielberg, but Amherst didn’t have a Film and Media Studies major yet. This proved to be a good thing for Amend, as he ended up having “a shotgun approach freshman and sophomore year,” in which he took all kinds of classes.

I was surprised to learn that he majored in physics. Amend jokes that “the same sort of insanity that makes someone be a physics major also leads them to choose to be a cartoonist professionally.” Insanity indeed: Whether his mindset was encouraged by his surroundings or came naturally, his tenacity certainly leaves a lot to be admired. Physics was the backup plan, a way to rationalize the money his parents paid for his education. He would only consider it as a career path if cartooning or film didn’t work out. Unexpectedly, however, his major has been helpful in making comics. “If I'm doing the four-panel comic strip and I've got the dialogue going in a certain place [and] I need a funny way to end this,” Amend explained, “it's sort of similar to doing a math problem or a physics problem.”

In his first year, Amend drew cartoons for The Student. Put under the pressure of deadlines and criticism, he honed his craft — often sacrificing his sleep. He recalls working on his cartoons at 1 a.m. with “people looking over [his] shoulder going are you done yet? Are you done yet?” Sophomore year, he was hired as an opinion editor.

In junior year, he took a break from the paper and started his own publication with one of his friends. The newspaper he made, The Amherst Enquirer, was a fun and silly alternative to the seriousness of The Amherst Student. It might have stories about, for instance, aliens spotted behind the Dean of Students’ Office.

Compared to many of his classmates who were headed in more “conventional” career paths like medical school, law school, or business school, Amend’s journey stands in stark contrast — though it’s not realistic for everyone to be able to make the same choices as he did. After graduating, he moved back to California to his parents’ house and drew cartoons in his free time as he looked for a job.

Finding “FoxTrot”

Rejection letters piled on. Meanwhile, he worked for a few months at an animation house in San Francisco. It was repetitive work, and he was only making around $8 an hour. He began to work even harder on his comics so he could leave his animation job. His perfectionist streak, while detrimental to his emotional well-being, helped him improve the quality of his comics. Hating most of what he wrote, he constantly revised. Gradually, the rejection letters got more and more positive, which motivated him to send in more of his strips. Getting published was an extensive process, one that took him years of practice, never knowing whether his hard work would even amount to anything.

Amend said that ideas come easy to him. He could make a great one-page outline for a novel or a movie, but the execution of writing the entire book or the script is the real challenge for him. Perhaps it makes sense, then, that “FoxTrot” — the short-and-sweet comic strip that has now been running for over 30 years — came to Amend in just one afternoon.

The family sitcom was already a tried-and-true concept, so Amend decided to make his own version of it. Compared to many cartoonists who were in their 50s and 60s, Amend was much younger, so he made his comic stand out by giving it a youthful tone.

Finally, after so many iterations of “FoxTrot,” he got a contract at 25 years old. And he’s been making comics ever since.

Drawing on a Deadline

Making deadlines is a huge concern for Amend’s work, given that the comics are scheduled to be published to the public, weekly. His rookie contract, which lasted for 20 years, was for a daily comic strip. Monday through Saturday strips were black and white, so he would try to finish them all in one batch. Sunday strips were usually larger and colored, so he would spend more time on them. Because the schedule was so demanding, he often worked through weekends.

Amend then renegotiated for a weekly comic strip, which was much more manageable. Typically, it’s a two-and-a-half-day workweek, but there’s a lot of flexibility. He likens it to writing a paper in college: It “doesn’t matter how I get there,” as long as he does. Still, he has to turn in his cartoons six weeks in advance — a backlog too long for Amend to comment on specific current events, but something he makes up for with “FoxTrot”’s frequent references to modern technology and pop culture.

He differentiates between two kinds of cartoonists: “Either they’re like me; they procrastinate a lot and wait until the last second, or they’re too worried about burnout and so they work way in advance.” Regardless, he said, “I don’t meet many who are normal and healthy.”

Meaningful Memories

On a personal level, making comics is not “fun” for Amend anymore — it has become work. But that doesn’t make his work unfulfilling. The comics are an outlet for him. They’re his own “little microphone.” His thoughts are potentially being read by millions of people, especially because he has made a big push to be on social media. To have such a wide platform is a rare thing, he acknowledges. And with the internet and the rise of webcomics, there are even fewer barriers for people to broadcast their thoughts.

Conversely, Amend describes teaching himself how to make an iPhone app as “the most fun I've had in a long time.” In high school and in college, he developed a love for computer programming. But to make the app, he had to learn a new set of skills. He read books, watched videos, and spent around 11 months start to finish making it. It was a simple quiz app from which he made almost no money, but it was an incredibly rewarding experience.

Being a cartoonist can be very isolating. It’s common for him to “miss having meals at Valentine and being surrounded by not just physics friends, but political science friends and economics friends and pre-med friends and just hearing all kinds of talk — academic talk or just social talk.” He misses the camaraderie and the environment where he was exposed to a multitude of disciplines and smart peers. Everyone was heading in their own directions, but connected to each other because this school brought them together. Ultimately, his advice to the current students of Amherst is to embrace this period of time, because we will never have it again.

Talking to Amend, I am struck by how much he laughs. He laughs in the middle of his sentences a lot, and it’s a quiet kind of laughter that only lasts a couple of seconds. Maybe he does it out of awkwardness and not out of humor, but I still appreciate that he does not take anything too seriously and faces his life with a desire to entertain. Both on and off the strip, Amend has not forgotten to find the absurdity of everyday life.

Comments ()