A Gentle Guide to David Foster Wallace

A spectral David Foster Wallace lingers in the depths of Frost Library, haunting those who dare to take on “Infinite Jest.” However, for those seeking a gentler introduction, Staff Writer Max Feigelson ’27 offers a roadmap through his labyrinthine literary world.

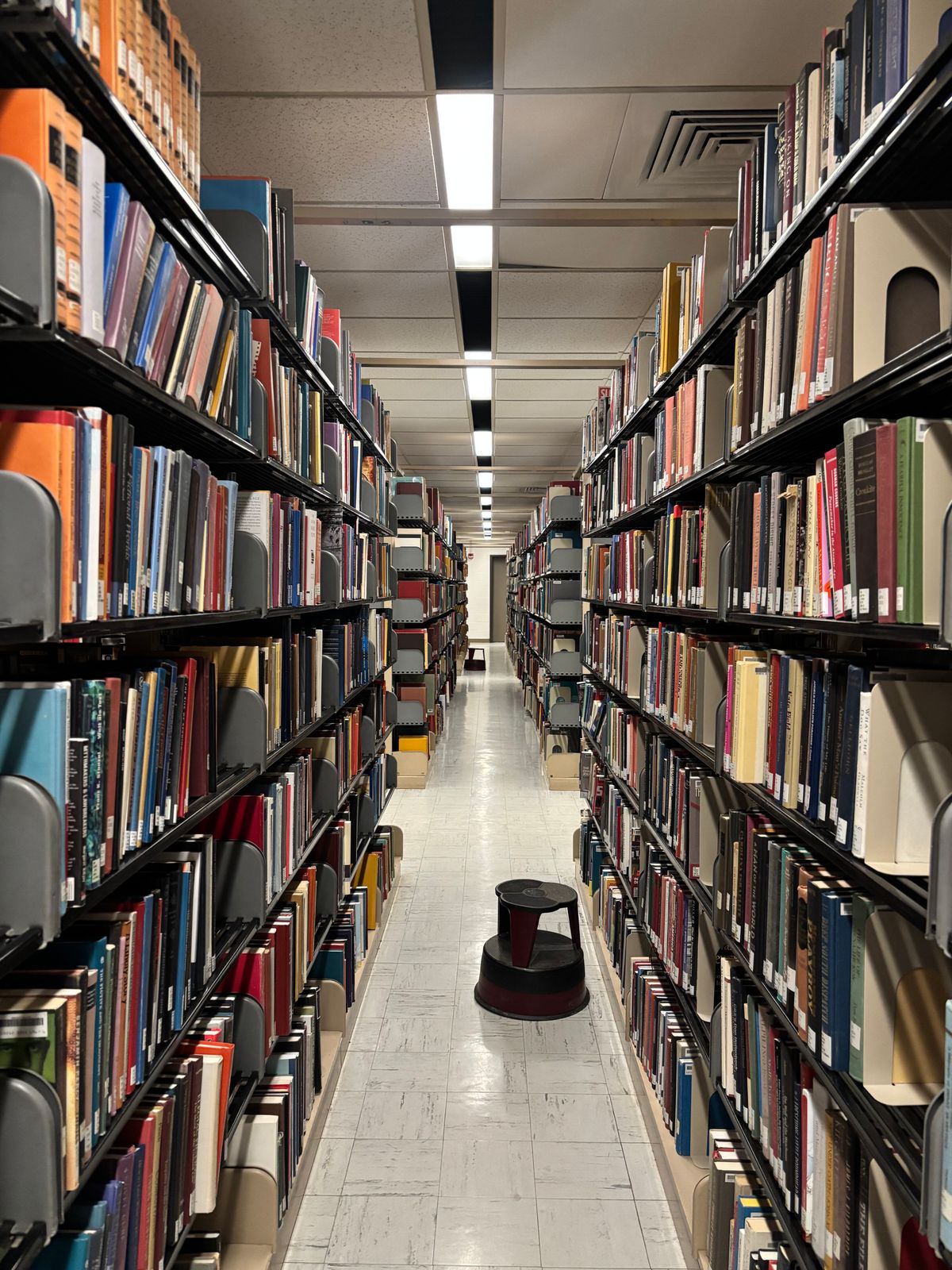

There’s a phantom haunting the C level of Frost Library. This ghostly presence has no desire to show you your Christmases past, nor does he have any interest in convincing you to kill your incestuous uncle. This ghost is tame compared with those of literary history, but if you dare write an essay or a short story in his presence, you’ll feel his watchful eye as you forget the difference between “consists of” and “consists in.” The bandana’d and unshaved author David Foster Wallace (DFW) is haunting the lower levels of our library, and if you have any interest in Amherst College or contemporary American literature, it’s best to get to know him.

As Amherst’s upperclassmen come to the end of their time at the college, they feel an obligation to plumb the depths of DFW’s legacy. But unlike Emily Dickinson or Robert Frost, whose works are sublime in their brevity, these upperclassmen find DFW’s books far too long to justify the effort. Frost Library has seen hundreds of students check out his most famous work, perhaps read about 30 pages out of 1,000, then promptly return “Infinite Jest” (1996) to the circulation desk. This reaction to such an intimidating tome is unfortunate but understandable (after all, it’s only his second-best book). This guide offers an alternative approach to DFW that takes his reputation and entire oeuvre into account. The goal is to guide you through a gentle submersion rather than a polar plunge into his works. I recommend the following:

Start small. Watch “The End of the Tour” (2015), a biopic starring Jason Segel as DFW and Jesse Eisenberg as a reporter for “Rolling Stone,” and check out some of DFW’s interviews. In contrast with his textual reputation, he’s remarkably soft-spoken, gentle, and ruthlessly anti-pretentious in his intelligence. I usually can’t stand the incessant yapping in podcasts and interviews, but DFW on video and in-earbud is a unique pleasure.

After this appetizer, go to the nonfiction. It’s designed to be popularly accessible and packed with equal parts incisive observation and legitimately funny jokes (as in, they will make you laugh and not just slightly exhale through your nose). Usually, you’ll hear praise for “Consider the Lobster” and “This is Water,” which are both great, but I’d start with “Ticket to the Fair”: a fairly straightforward account of DFW’s experience watching obese and joyful rural Americans competitively clog, deep-fry everything, and evaluate ungulate aesthetics at the Iowa State Fair. This is a good introduction to his narrative style, which might be characterized by its ambition to capture two mutually exclusive realms of experience — his diluvian internal monologue and our kaleidoscopic external world. At every moment, his eye turns towards his mind while he projects it into space so that it may float and observe without his input. If you enjoy this kind of experiential, Hunter S. Thompson-esque creative nonfiction, I’d also recommend “Shipping Out,” about DFW’s time on a cruise ship, and “Big Red Son,” a particularly depressing and disturbing piece about the Adult Video Network’s annual Pornography Awards.

If you’re more of an argumentative nonfiction person, I’d tackle “Authority and American Usage,” a review of Bryan A. Gardner’s “A Dictionary of Modern American Usage” gone delightfully haywire. This would be especially far up the alley of anyone who loved George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” and wants another fix of that strange but self-evidently important crossover between linguistics, literary theory, and politics. This essay would also be good for anyone who’s ever resented their English professor for imposing allegedly colonial grammatical rules on your right to free expression. If neither of these descriptions applies to you, I imagine that reading this essay, by itself, could make you a better writer. Not only did it help me to improve, but it gave me my first sense that improvement requires the confidence and humility to realize when your writing isn’t good simply because you tried your best.

With this preface, you’ll now have an understanding of the way in which DFW’s writing functions simultaneously as earnest prose and metatextual mad science experiment. You’ll understand the effect and inherent playfulness of his footnotes, interpolations, invented acronyms, and narrative fragmentations. You will now be able to read and not try to read “Infinite Jest.”

When I read “Infinite Jest” over Covid, it became an obsession. My mother watched me paw back and forth between the main text of DFW’s novel and its footnotes every day for weeks before commenting that it didn’t seem as if I was reading a book as much as I was playing with a toy; the book compelled me to pay the same kind of attention that my much younger self paid to his Hot Wheels and Rainbow Loom. This is to say that reading “Infinite Jest” is hardly comparable to reading “War and Peace” or “Middlemarch,” which I could only read as I would read any classic novel. Better corollaries in the realm of long books would be “Ulysses” or “Moby Dick,” each of which disturbs the classic conventions of the written word.

The book has two main characters: Hal Incandenza, a Hamlet-inspired top-ranked junior tennis player, and Don Gately, a hulking former thief and recovering drug addict with a giant square head working as a counselor at a halfway house. These two worlds are inverses of each other. As the supposedly successful and allegedly mentally sound junior tennis pros descend into hedonistic lives of pharmacological and televisual addiction, the supposed failures and mentally ill addicts at the halfway house ascend to sobriety and maturity. This is the simplest possible summary of a book that includes a crucial plotline concerning a Quebecois terrorist cell called “Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents” consisting entirely of members without legs; a movie created by Hal’s father, named “Himself,” which is so addictively entertaining that all those who watch it starve themselves to death; and a dystopic future America, now called the “Organization of North American Nations,” (“ONAN,” like the Biblical masturbator), in an “experialist” trade war with Canada where both sides attempt to force the irradiated territories of New England onto one another.

This sample of what the novel has to offer may already demonstrate the kind of attitude one has to take towards DFW’s opus: You have to be ready not to take things too seriously. Just as “Moby Dick” dedicates a chapter to a proof that whales can never go extinct, “Infinite Jest” dedicates a hundred pages and dozens of complex and mathematically rigorous footnotes to a description of “ESCHATON,” a geopolitical nuclear war simulation game played by lobbing tennis balls (ICBMs) into various squares on a tennis court. To be sure, these moments of absurdity serve as only the first half of a classic two-part knockout punch: comedy to tragedy, laughter to anhedonic depression.

If anyone’s keeping score, this guide has excluded the novel DFW wrote as one of his two theses at Amherst, “The Broom of the System.” DFW described this book best when he said it sounds like it was written by a “very smart 14-year-old.” It’s only really worth picking up if you’re curious about Wittgenstein’s potential applicability to fiction, but even then, you’d be better served by reading David Markson’s “Wittgenstein’s Mistress” or Tom Stoppard’s “Dogg’s Hamlet.”

Perhaps the most controversial take in this guide is my claim that “Infinite Jest” is merely the second-best DFW novel after his unfinished book “The Pale King.” Controversial, maybe; correct, certainly. Whereas “Infinite Jest” bulges under the conceptual weight of its own Sierpinski-organized plot, half of which takes place outside of the book’s own timeline (look up a graph to see what I mean), “The Pale King” gently ushers its reader into a thoroughly normal world: an IRS examination center in Peoria, Illinois, in 1985.

Kafka turned Gregor Samsa into a cockroach; DFW turns his IRS employees into secret superheroes: They each have miraculous but altogether useless powers — one man is able to levitate several inches off of his seat — that are only activated when their attention is fully committed to the monotony of tax examination. Normalcy, tedium, ennui: these are the thematic veins running through the narrative body.

The book is unfinished, but in his notes, DFW wrote that even the finished novel was meant to set up several large conspiracies and character arcs that would never be satisfactorily resolved. This book is, therefore, the one that can be best compared with “Gravity’s Rainbow,” “The Crying of Lot 49,” and the rest of Thomas Pynchon’s works; DFW, however, is more earnest about people and the relationships between them here than his postmodern colleague ever was. Perhaps this is most clear in “Something to Do With Paying Attention,” a chapter about a tax examiner’s life journey from a spiritually lost drug addict to a satisfied tax examiner, largely as a result of a single speech on the Achillean heroics of contemporary tax collectors. Embarrassingly, this section contains my high school yearbook quote: “Enduring tedium over real time in a confined space is what real courage is. Such endurance is, as it happens, the distillate of what is, today, in this world neither I nor you have made, heroism” (Covid sucked). If you’re looking for another literary introduction to DFW, “Something to Do With Paying Attention” (2022) would make a good one as it has recently been published as a standalone novella.

I don’t promise that you’ll enjoy this kind of writing. He’s no Hemingway; Strunk & White would probably have an aneurysm reading any of DFW. He’s a problematic guy if you look into his backstory. There’s a disgusting culture of idolizing his suicide as the tragic death of yet another depressed artist. For a certain kind of person, though, his turns of phrase and pyrotechnic innovations scratch a particular neural itch. Maybe one of the core ironies of his work — the execution of which is intentional — is that his incessant interest in the psychology and politics of addiction is replicated in his style. One finds oneself flipping pages serially, hoping for just one more turn of phrase to spark the basal ganglia. And when that phrase finally arrives, the resulting high is so overwhelming that you may find yourself at page 1,000 subconsciously. If you’re paranoid about the prospect of addictive literature, DFW may have already succeeded. To paraphrase a poster on Michael Pemulis’s wall in “Infinite Jest,” and on mine in the Zü: “Yes, you may be paranoid, but are you paranoid enough?”

Comments ()