College Reviewed Protest Policy Over the Summer, Amid National Reckoning on Campus Speech

After a spring defined by political action, many campuses tightened protest restrictions over the summer. Amherst's administration also updated their protest policies, though changes were more minimal. The process still offers insight into complex campus dynamics.

Prohibitions on protests during certain times of day and night. Restricted campus access. Orientation sessions on free speech and protest policies. These are some of the changes enacted at campuses across the country this fall, after a summer full of administrative reflection on protest and free speech policies.

Nationally, summer break served as a time for college administrations to reflect on their policies and approach to student protests after a spring semester defined by political action. News outlets covered institutional processes, with the New York Times reporting that college administrators “used summer break to huddle with police commanders, lawyers, trustees and other administrators to rewrite rules, tighten protest zones, and weigh possible concessions.”

Over the summer, Amherst’s administration joined these other colleges and universities in updating our campus protest and posting policies, part of a yearly review process. These policies govern student protest actions as well as the use of posters and flyers.

Generally, policy changes here were smaller compared to those enacted on some other campuses. In some cases, Amherst’s policy changes actually widened the range of permitted behavior — the administration removed a ban on masking at protests, for example, and now allows for non-registered student organizations to post flyers.

President Michael Elliott and Dean of Students Angie Tissi-Gassoway said they endeavored to make the policies more clear for students and more practical for the administration.

National context

Amherst’s updated policies follow a spring marked by widespread student protests related to the war in Gaza. At many colleges and universities, students established Palestine solidarity encampments, often with demands that institutions divest from the Israeli military.

During many colleges’ summer policy reviews, administrators sought guidance from outside organizations like the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), both of which released guidance for administrations over the summer. The ADL’s packet focused on clearly communicating protest policies in advance and protecting Jewish students, while the CAIR’s guidance emphasized negotiations with protesters, minimizing police response, and effective defense against the doxxing of students.

Some campuses have adopted bans on stickers and signage without advance notice; others have banned wearing masks for the purposes of hiding one’s identity while protesting.

Indiana University prohibited protests between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m., garnering national media attention; The University of South Florida banned all protests after 5pm, as well as all protests in the final two weeks of the semester.

New York University created new conduct codes specifying that the use of “Zionist” or “Zionism” in a derogatory way violates the school’s non-discrimination and harassment policies.

At some schools, such as Vanderbilt University, sessions on free speech and protest policies are now part of freshman orientation.

At Amherst, however, policy changes were less dramatic.

Policy changes at Amherst

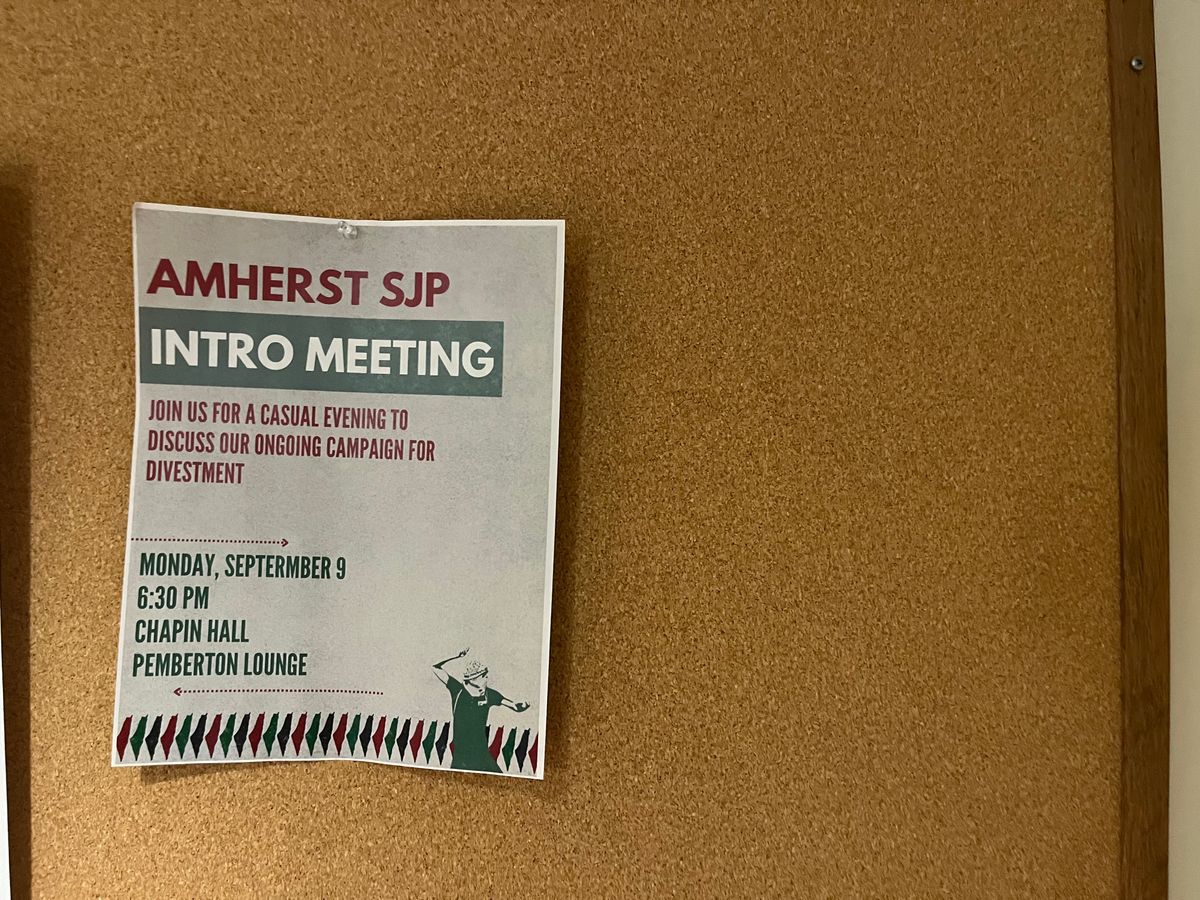

Last year, no encampment was erected on Amherst’s campus, but groups such as Amherst Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) — formerly Amherst for Palestine — and Jews for Ceasefire organized efforts around divestment and other demands. At the end of the semester, both the Association of Amherst Students (AAS) and the faculty voted in favor of resolutions calling on the Board of Trustees to divest from companies that supply equipment to the Israeli military. Over the summer, Elliott and the Board announced they had unanimously voted not to divest.

On Aug. 28, Elliott sent an email to the college community with the subject “Our Commitment to Free Expression.” The new statement linked to the Statement on Academic and Expressive Freedom as well as the Protests and Free Expression Policy and the Posting Policy, the latter two of which were updated over the summer.

In line with past communications, the administration emphasized the protection of free speech rights while placing limits on protest activity that disrupts academic and administrative function, including speeches and events hosted by the college.

One major change from the summer is that the protest policy is now shared between ACPD and Student Affairs. Before, it was housed entirely within ACPD’s domain.

“That was a summer change to really make sure that it’s clear that we are collaborating on those policies together to work with students,” said Tissi-Gassoway.

While previous policy has already prohibited protests and demonstrations that block entrance and exit from buildings, it now also prohibits obstructing public pathways indoors and outdoors.

Elliott explained that while, last semester, “Nothing we saw of this campus blocked egress in and out of buildings or restricting access to pieces of a campus … there were campuses where that took place, and so we wanted to make sure that that was clearly prohibited policy.”

The college’s protest policy and the student code of conduct have long required that anyone on campus identify themselves by name when asked by college personnel. This point was emphasized this summer, as the policy’s language was changed to say that protesters “must share” their identity rather than that they are “expected to share.”

Importantly, the administration removed an existing prohibition on masks as part of protests. Elliott said that last year the administration had not been aware of the anti-mask policy, which was written in 2017.

“Masks mean something different to us in the community now,” Tissi-Gassoway said, “We removed that from the policy, given that people use masking to protect their health and safety.”

A few changes were also made to the posting policy. Previously, only individuals and registered student organizations (RSOs) technically had the ability to post flyers, posters, etc. This was changed to any student organization, including new student organizations petitioning for registration or other non-registered organizations. It also removes the requirement to identify an individual’s contact information on a poster. Now, only an organization or individual’s name is needed.

There were also some smaller tweaks. The number of posters about a certain event or campaign allowed in a given area was changed from one to two. Throughout the policies, more specific names, titles, and emails appear instead of instructing students to contact a given department to receive permission, for example, to post a banner at Frost or Val.

In a consistent language change, the administration removed the word “core” from policies about activity that disrupts the “core administrative and academic functions of the college” so that now it simply reads “administrative and academic functions.”

“We realized just how vague that term, ‘core,’ was,” Elliott said.

Summer process

Each summer, Student Affairs and other departments review and update their policies to ensure their relevance and effectiveness. This summer’s review of the free expression, protest, and posting policies was part of this regular process. However, as Elliott said in an interview, “Policies like these are going to be read under a different degree of scrutiny than they were just a year ago.”

Tissi-Gassoway and Elliott both said that their focus in reviewing the protest and posting policies was to ensure that they were clear, enforceable, and content-neutral.

Elliott and Tissi-Gassoway were following other schools’ policy and in touch with other administrations — Tissi-Gassoway meets monthly with the other NESCAC Deans of Students. They also took note of the unique conditions that shape policy on each campus, and the advice coming from national organizations.

Elliott and Tissi-Gassoway also took into account how the protest and posting policies functioned last semester.

There was only one instance in which a speaker was shut down: President Elliott himself at a reunion weekend event, when a group of protesters took the stage while he was giving a speech.

“Our students were incredible, and they worked with us in all kinds of different ways,” Tissi-Gassoway reflected, “and there were moments that definitely … pushed the boundaries, but … we were able to work together. And so I hope that that is … what happens if our students decide to protest again this year.”

“I think our policies served us well last year,” Elliott said, “The revisions that Student Affairs made were really … in response to the only concern that I think I heard last year [which] was that … there [are] areas where we could clarify.”

For this reason, Elliott sent out an email update to the college community prior to the academic year’s start.

“We’re also under no illusions that a single email does that,” Elliott said, and mentioned that the administration is thinking through creative ways to ensure students are aware of policies.

Disciplinary response

Much national attention has been on the disciplinary response to protests at different schools. In some cases, police response has turned violent; other schools have issued expulsions and arrest warrants for student protesters.

Tissi-Gassoway and Elliott said that at Amherst, the disciplinary process for a protest policy violation would be no different than any other disciplinary violation — the college would first reach out for a meeting, and then students would move through the community standards process.

“We’re an educational institution. We’re not a punitive one,” Tissi-Gassoway said, “We want you to actually be experiencing and learning and making mistakes and understanding what your responsibility … is to the community.”

When asked about the potential for involving law enforcement, Tissi-Gassoway said: “I don’t arrest students. I don’t issue trespass orders in that way. That would have to be through our Amherst College Police Department … It would be because something has happened that is very serious on our campus. I think we have a very high threshold there.”

Elliott also said that while he understands students’ desire to know about specific consequences, “it would be out of character for us as an institution” to designate, in advance, specific disciplinary actions for specific violations.

“We don’t handle any disciplinary matters in a formulaic way here,” he said, “That is part of being primarily an institution for students, which is that we ask about context … that’s the difference between us and town police.”

However, both Elliott and Tissi-Gassoway underscored that students need not fear extreme and abrupt responses.

“Students … have a really clear process … and the code is bound to that. So it’s not just gonna be like, ‘you’re out of here,’” Tissi-Gassoway affirmed.

“Putting guidelines around free expression is one of the things that allows us to support it,” Elliott said, “It allows us to ensure that there are forums and boundaries. It also allows everybody on campus to understand what the rules are and how they’re expected to engage with them.”

Elliott also noted his concerns about the potential for counterprotests that have turned violent on other campuses, and said that he views college guidelines about protests, and the involvement of Student Affairs or ACPD, as protecting the safety and security of anyone involved in protests.

“I actually think these policies and what we’ve done this year allows for a little bit more flexibility to understand how to be responsible on campus as a student and be engaged,” Tissi-Gassoway said.

The year ahead

Amherst Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), formerly Amherst for Palestine, responded to the updated protest policy in a statement to The Student.

“The changes to the college’s protest policy are not a major concern for us — we don’t anticipate that these changes will help or hinder our efforts as we continue to fight for divestment,” they wrote.

“That said, the administrative decision to revisit the protest policy in the wake of the pro-Palestine student uprisings last spring tells us that the college is wary of pro-Palestine protests disturbing college operations,” they said, “We are taking this opportunity at the beginning of a new academic year to double down in our commitment to ensure that business as usual cannot continue until Amherst divests from Israeli genocide and apartheid.”

Despite the Board’s vote against divestment this summer, Elliott said that the administration would continue to be open to dialogue with protesters making those demands.

“This is a place where our entire free expression policy is about making sure it’s a place where we can have continued dialogue, disagreement,” he said, “And that’s, to my mind, one of the litmus tests ... one of the reasons that we prohibit, for instance, shutting down a speaker ... So of course we’ll continue.”

Tissi-Gassoway also mentioned that she is working with the AAS E-Board on a future town hall and forum opportunities to receive student feedback on policies.

Further concerns

Tissi-Gassoway also spoke about the protest dynamics within the Five Colleges. As with the NESCAC, she meets regularly with the Five College deans and said that they have discussed how to “support each other” as they navigate protests.

The University of Massachusetts, Amherst stands out as a unique environment in which, as a state school, state police are part of the response when protests violate policies.

Tissi-Gassoway mentioned discussions about what would happen if an Amherst College student were to be arrested at a protest at UMass or any other college.

“If [students] were to go to any other college and be protesting or participating in their activism ... students have a right to do that … [and] I think, for the most part, Amherst College students are considered visitors on other campuses, if they’re not enrolled in class, so our students are bound to their visitor policy. And we have no control of that,” Tissi-Gassoway said.

Middlebury College, another small NESCAC school, released guidelines for this year similar to the ones at Amherst. There was an encampment at Middlebury last spring active for about two weeks, which disbanded after Middlebury President Laurie Patton made a statement calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza.

Middlebury’s new guidelines include a note about a “sense of fatigue … experienced by nearly every member of this community: student organizers; students with divergent views of the situation; staff and faculty members … We are also mindful of the fact that last year, many additional resources were deployed, especially the time of our staff … to support and ensure open expression, respectful dialogue, safety, well-being, and compliance.”

I found the inclusion of this note interesting, and I asked Elliott and Tissi-Gassoway if they shared its sentiments.

“I do worry about the fatigue,” Elliott said. “Supporting students and supporting a community where protests, free expression are part of the fabric requires a lot of work, and … we’re in a moment when … small missteps can escalate into national news stories, and it’s a challenge for … the workers who support students, to work under that pressure.”

That being said, “It doesn’t mean that we’re going to be any less committed to it, this is part of who we are.”

Comments ()