CRESS Policing Alternative Faces Institutional Barriers

In 2022, the town of Amherst created the Community Responders for Equity, Safety, and Service (CRESS). Staff Writer Ana Mosisa ’24 investigates CRESS’ initial shortcomings and the current state of the program.

Two years ago, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, the town of Amherst passed a resolution that established an unarmed community safety and alternative policing force. Born from the values of anti-racism and equity, this resolution created the Community Responders for Equity, Safety, and Service (CRESS) — a task force of eight community members trained in behavioral health, mental health, mediation, and other social services surrounding public safety. The CRESS program launched in September 2022, reflecting a significant step in the direction of racial justice, community safety, and political accountability.

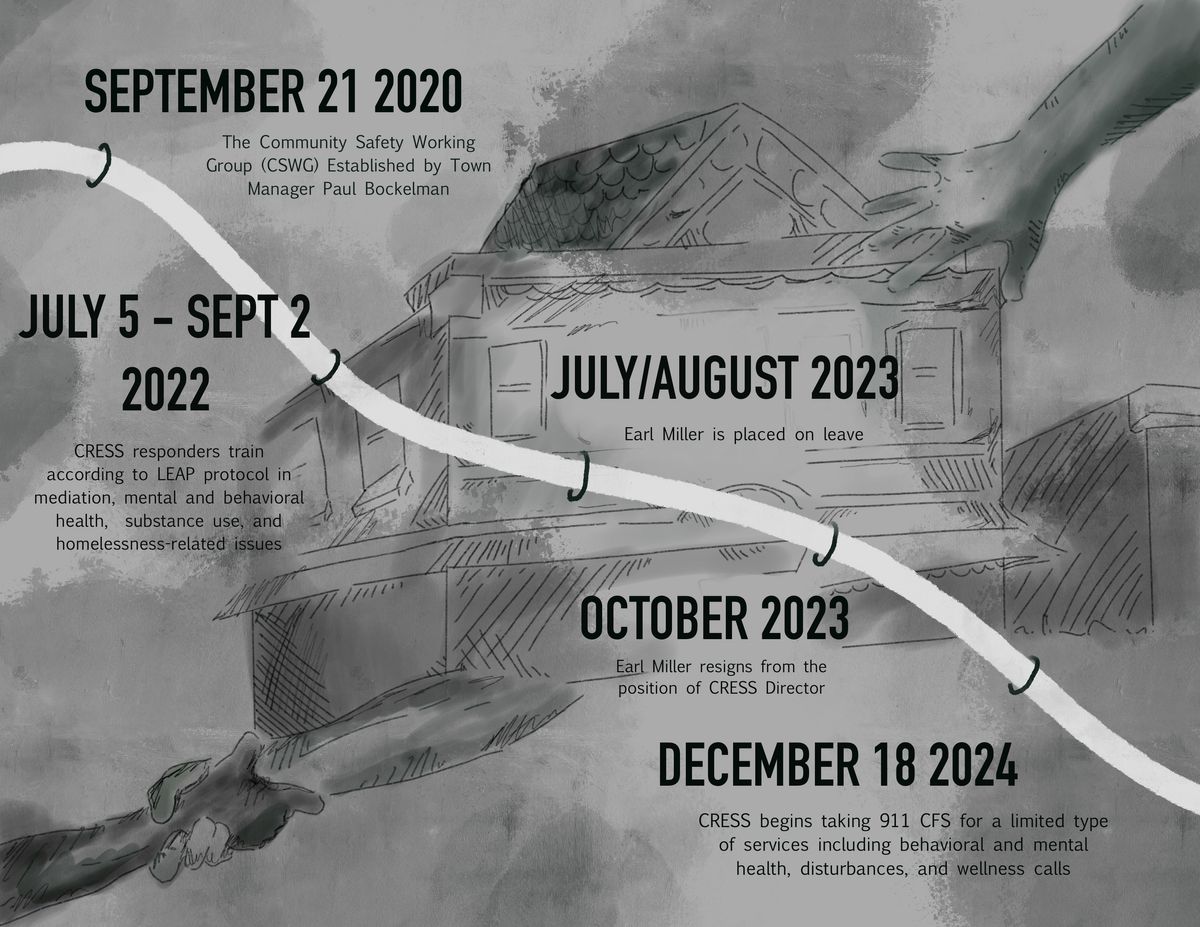

In the past year and a half, however, internal issues, delays in protocol, and community controversies have plagued the program, leaving a pile of unanswered questions in their wake. Even though CRESS was established to provide alternative responses to non-violent calls for service (CFS), the civilian responder group was denied town approval to respond to 911 calls from the program’s inception in September 2022 until this past December, when the town finally approved for CRESS to respond to a “limited range” of police calls. Additionally, last July, town leadership placed the program’s director, Earl Miller, on leave indefinitely. Amherst Town Manager Paul Bockelman said in a town meeting that Miller’s leave is an “internal personnel matter” pending a third-party investigation. Months later, in October, Miller announced his formal resignation from the director position. Since his initial leave, three additional members of the responder group have resigned, leaving only five members as of February 2024.

Town residents and CRESS stakeholders alike have expressed dissatisfaction over the past year and a half regarding the delays in CFS approval, the mystery surrounding Miller’s forced leave, and the instability following several months of transitional CRESS leadership. In this article, I review the state of CRESS from its beginnings to the current day, drawing details from research and interviews with people closely involved in the program. What exactly prevented CRESS from responding to 911 calls? How did CRESS operate for a year and a half, while paid by the town, without carrying out their job according to original town protocol? And further, what happened regarding Miller’s initial leave? To understand how CRESS seemingly flipped over on its side, I go back to the program’s beginnings, uncovering key facts, expectations, and challenges that paved the way for the program’s later struggles.

CRESS Formation and Town Initiatives

The 2020 Black Lives Matter movement set the stage for a wave of policing reforms throughout the country, introducing anti-racism initiatives and alternative policing projects into popular discourse. Following the police murder of George Floyd, the town of Amherst made several resolutions to provide more equitable and anti-racist policing. These resolutions established the Community Safety Working Group (CSWG), an anti-racism committee tasked with recommending alternative public safety services and new oversight frameworks for the Amherst Police Department, both of which serve the goal of reducing deadly armed policing. That summer, after thorough national research and town data collection, the CSWG called for several projects, including the creation of a civilian first responder group. Town Councillor Ellisha Walker, an original member of the CSWG, expressed that their research suggested a general lack of trust from Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) towards the police, showing that many were hesitant to call the 911 line. The CSWG May 2021 report found that “[p]articipants repeatedly identified racism and bias in police and their police work. They also repeatedly reported a sense of the BIPOC community being overpoliced and experiencing excessive surveillance by the police.” Walker reiterated the CSWG’s findings. She claimed, “The police have this growing awareness of who BIPOC kids are, and where they live.” She also indicated a lack of general social services and youth programming in the area, leaving kids around the town with nothing to do after school.

The CSWG recommendation thus urged for an alternative set of responders, unarmed and separate from the police department, to respond to non-violent 911 calls, aiming to “reduce negative police interactions and justice system involvement for people of color,” according to a town report by the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP), a town contractor during the creation of the CRESS program. Russ Vernon-Jones, another early member of the CSWG, said that the group also pushed to have a BIPOC director for the program, hoping for these efforts against racism to be at the center of the civilian responder group’s ideology and practice. The town finally agreed to create CRESS following a stipend from the state of Massachusetts.

Following this, the town hired LEAP, a research-backed public safety contractor, to collect and analyze data regarding police calls for service (CFS) in Amherst, as well as design protocols for CRESS responders and the dispatch center, which receives and redirects 911 CFS. To this effect, LEAP devised a flagging protocol for Amherst 911 dispatchers to discern which calls fall into non-emergency and other low-priority categories, such as mental health or dispute resolution. Supposedly, those calls were the kind that CRESS, rather than armed police officers, was meant to respond to. Currently, about two dozen cities in the United States operate programs similar to CRESS, and “have answered hundreds of thousands of calls with no safety concerns,” according to Amos Irwin, a LEAP Program Director.

LEAP Report Findings

The LEAP report found that in 2019, approximately 36 percent of the total 15,244 CFS to 911 in Amherst were minor and/or non-violent, mainly including minor disputes, mental health, substance use, and homelessness-related issues. LEAP’s general community responder report, estimates that on average 23 to 30 percent of nationwide 911 CFS are low-risk and optimal for community responders. The town of Amherst surpassed this projected number by 6.0 percent, indicating an above-average rate of low-risk calls. On the other hand, LEAP found that calls which require a police response, including security, and preventing or stopping a serious crime, made up just under 15 percent of 911 calls. These data points indicate that low-risk calls in Amherst more than double their share of high-risk calls.

LEAP’s data suggested that a program like CRESS would prove well-suited to a town like Amherst, where crime is low and diversity numbers are rising annually among university populations in the area, including Amherst College and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Beyond LEAP’s 2021 report, the town also received $450,000 in grant funding from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health to support CRESS’ alternative policing model. CRESS, with the support of the state, the town, and LEAP, seemed capable of helping Amherst achieve its anti-racism initiatives. So how did CRESS’ problems begin?

From The Source: What Do We Know, and What Remains Unknown?

Amherst community members were promised an unarmed, mediation-oriented, and health-focused CRESS program that would increase town confidence in 911 services. However, from the start, CRESS struggled to gain the green light to respond to 911 calls. Irwin first heard of CRESS’ continuous struggles to get 911 CFS access in January 2023, even though CRESS had been operating for four months already. Some individuals in the town, like Russ Vernon-Jones, have expressed their dissatisfaction publicly. Vernon-Jones claimed that he alerted the town manager in March 2023 that CRESS was not receiving 911 calls. Months later, in October 2023, Vernon-Jones expressed his concerns about the longstanding struggles with CRESS. In an Amherst town council meeting, he said, “Responders are still not receiving 911 calls even though the policies, protocols, technology, and training for that have all been in place since January.” Vernon-Jones said that one of the key factors shaping delays in CRESS 911 call access is “because of the refusal of dispatch.”

Bockelman’s office declined to comment but deferred to CRESS Implementation Manager Kat Newman, a member of the new town-appointed CRESS leadership team which began in September 2023. That team includes officials from the Fire Department and the Police Department, Chief Tim Nelson, and Sgt. Janet Griffin respectively, as well as a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Director, Palema Nolan Young, and Newman. “We anticipate the department receiving dispatch calls in the coming months,” Newman wrote to The Student. An anonymous source echoed Vernon-Jones’ concerns about dispatch. “It’s the golden piece of the puzzle. The success of CRESS really starts with dispatch.”

The Past Year and a Half of CRESS Operations

Since CRESS’ initial operations in September 2022, the restriction upon 911 CFS access has ultimately prevented the group from minimizing potentially dangerous police interactions, which was the program’s initial purpose. However, under the leadership of former director Earl Miller, the CRESS program initially found numerous ways to support the community. Through more immersive methods, CRESS carried out services that applied their mental health, homelessness, and substance abuse training. In the winter of 2023, Miller and the initial eight CRESS responders were reportedly going out into the cold to bring unhoused people into homeless shelters. The Jones Library was a popular location for temporary housing. Councilor Walker remarked that CRESS performs plenty of odd jobs around the town, including lending help to town events and subsidiary town services like supervising community service programs for students. Often these services neglected to call upon CRESS training in mental health, mediation, and other CRESS services. However, as Vernon-Jones articulated, Miller ensured that the group engaged with community needs.

The delays in 911 call access ultimately shifted the nature of CRESS’ role and initial job description and as a result, three out of the eight initial members have resigned.

Another key aspect of this shift in CRESS operations includes a drift away from the program’s early anti-racism initiatives. While Miller’s prior role in CRESS and his anti-racism training bespoke the early ambitions of CSWG, his resignation leaves some town members feeling discouraged. Vernon-Jones, a staunch advocate for anti-racism, said, “You hire a Black man, and several BIPOC responders, and for a year they were not allowed to perform the job they had signed up for. I think it is an example of systemic racism in the town of Amherst.”

Final Thoughts

As Vernon-Jones said, the town’s initial objective for CRESS, as an alternative policing unit, clearly has not been met over the past year and a half, and the program’s future is becoming increasingly uncertain. As of February 2024, neither a new director nor replacement staff members for the three who resigned have been hired. Miller’s future with the program also remains unclear. The LEAP model for equitable, unarmed community aid responders ultimately has yet to be fulfilled, altered by the ailments of small-town politics.

And yet, the town of Amherst, as home to two major universities, hosts an increasingly diverse population in need of community support surrounding public safety. Given the pressures of structural racism, many BIPOC individuals in Amherst have felt singled out, and even unsafe, under the scrutiny of police. With clear calls for anti-racism efforts in Amherst, a $450,000 state grant for unarmed public safety responders, and a protocol for training and operating the program, CRESS has great potential and should be a high priority for the town. In the coming months, community members are urging the town of Amherst to state their intentions for CRESS with complete transparency, as well as their intentions regarding CRESS involvement with Amherst police. Some members of the community fear that CRESS will gradually continue integrating with the police until eventually it becomes a subsidiary of the Amherst Police Department. While the future of CRESS has yet to unfold, it is clear that the town must take amendments to bring integrity to the program’s full breadth of potential for reducing avoidable armed policing.

Comments ()