The Duke's Notebook: The "Barbaric" Music

Writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. — Theodor Adorno

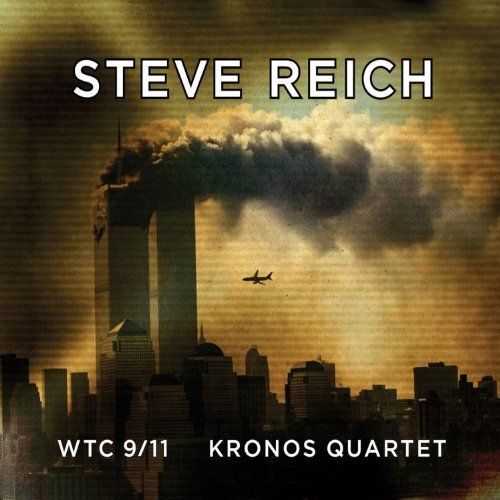

Steve Reich, the American composer celebrated for minimalist compositions like “Piano Phase” (1967), “Clapping Music” (1972) and “Different Trains” (1988), just released a piece entitled WTC 9/11 for string quartet and prerecorded tape. Commissioned by his long-term collaborator the Kronos Quartet, it premiered at Duke Univ. this March as a musical tribute to the 10-Year memorial of the Sept. 11 attacks.

The album reminds me of Arnold Schoenberg’s “A Survivor from Warsaw,” which was composed and premiered more than 60 years ago, a few years after the end of the Second World War and the Holocaust. Both of these pieces are musical tributes to catastrophic events in human history — the Sept. 11 attacks and the Holocaust — that profoundly influenced the composers, Reich as an American and Schoenberg as an Austrian Jew.

In “WTC 9/11,” the tape consists mainly of recorded human voices and plays a central musical role. Reich draws most of his musical ideas by matching these voices with definite pitches on the string instruments. His music simply echoes and follows the flow of these voices without any other formal trajectory. The first movement “9/11” starts with an off-hook tone, followed by the higher strings that match its steady rhythm and its piercing sound of a minor-second interval.

This combination dominates the first and second movements as an intervallic and rhythmic motive. Then comes a series of fragmented voices from the North American Aerospace Defense Command and the New York Fire Department, which chronologically retell the attacks. Again, the strings “double” the voices with their definite pitches, as if they were their shadows and echoes. Reich applies the same compositional strategy in the second movement “2010,” where he turns his focus from the past to the present, and uses voices from the interviews conducted in 2010, in which his New Yorker neighbors recall their memories.

The Schoenberg is scored for narrator, men’s chorus, and orchestra. A 12-tone composition, its music is organized around carefully arranged and transformed rows in the chromatic scale, and follows the principle that, in contrast to tonal music, all of these 12 notes should receive equal attention. The text, a little longer than 400 words, is written by Schoenberg himself but drawn from real survivor accounts. It tells the story of a survivor from a concentration camp, where he experienced severe violence and witnessed some other victims chanting Shema Yisrael, the most sacred Jewish prayer, “as if prearranged” upon being sent to the gas chamber.

Like Reich, Schoenberg organizes his music around the text. Even though his music has a formal design of expositional, developmental and recapitulative gestures, it mainly adheres to the motives of the words and is dedicated to a highly literal text-painting, as if its servant. Interestingly, in the score Schoenberg marks the narrator’s text with musical notation that indicates a highly precise rhythm (with 32nd notes and triplets) and an almost melodic contour (with accidental signs).

It seems as if Reich and Schoenberg find it problematic to compose music for a human catastrophe like the Sept. 11 attacks and the Holocaust. It is then necessary, in order to achieve this musical goal, to submit their music to the power of spoken words.

Why, for these two accomplished composers, has music become troublesome and powerless?

Do they share Adorno’s opinion that any kind of art based on or addressing a catastrophe where the victims experience horrible violence, fear, torture and death, is an abuse of the victims and therefore “barbaric?”

Both of the composers do not give up when faced with this challenge. At least, they try to hide their musical incapacity by “musicalizing” the text materials they use: Reich turns human voices into definite pitches and musical motives, and Schoenberg uses musical notation for spoken parts, even though it is impossible for the audience to see.

Furthermore, near the end of their music, both arrive at some kind of “wholeness” and “transcendence,” a requirement that the abstract nature of music dictates. Both are such a transcendental moment due to having “music within music” or so-called “phenomenal music.” In the third and last movement of “WTC 9/11,” the words of the interviewers give way to anonymous singing and chanting in the tape. Such phenomenal music does more than offer fresh musical materials: for the first time, it is impossible to tell whether his music dwells in the “past” of the first movement, or in the “present” of the second. He thus blurs the line once clearly drawn between the two distinct reference points, and proceeds into another dimension undefined in temporal terms. Reich also points out directly in the tape the meaning of its title “WTC:” not only “World Trade Center,” but also “the world to come.” Clearly he brings in a sense of hope in the coming future, after the wounds of the past and the present, and unites the whole piece into one with an affirmative statement in the tape “and there is the world right here” (again “doubled” by strings) and the final return of the opening off-hook tone motive.

Schoenberg’s “A Survivor” ends with the dramatic unison chanting of Shema Yisrael by men’s chorus portraying the Jewish victims. Plainly set in Schoenberg’s 12-tone row and its transformations, this chant most clearly displays the foundational blocks — the tone rows — of Schoenberg’s compositional process at the end of the piece. This is also a moment of phenomenal music that coincides with the actual musical transcendence. As the narrator depicts the Nazi soldier counting one after another the Jewish victims who will immediately be sent to the gas chamber, the orchestra simultaneously starts its own build-up with the repetitive triplet gestures joined with one instrument after another. This gradual accumulation of agitated sound and texture is similar to the middle section in Schoenberg’s “Premonitions,” one of his most celebrated orchestral works full of gestures of fear and violence. When the narration hits its climax and gives way to the “grandiose” chanting of Shema Yisrael, the orchestra “explodes” dramatically into a new world when the music stops literally depicting the texts yet merely accompanies the chanting with its own gestures.

Such transcendence, which serves as the core of our understanding and appreciation of serious music, is exactly what makes both pieces “barbaric.” By having such transcendental moments with phenomenal music in their work, Reich and Schoenberg seem to utilize the victims of those human catastrophes as ladders by which they reach their transcendental musical goals, as if they were not victims but our “martyrs,” and as if the musical tribute were a celebratory memorial.

Martyrs for our hopeful “world to come.” Martyrs for the Jewish beliefs embodied in Shema Ysroael, “the old prayer they had neglected for so many years — the forgotten creed,” or even for the new State of Israel in the Promised Land (Schoenberg became a devoted Zionist following the Second World War). In fact, this idea of “martyrdom” embedded in Schoenberg’s “A Survivor from Warsaw” suggests such a horrible connection with the etymology of the word Holocaust: the burning of a whole animal sacrifice to the gods.

But whoever really chose to die, or to “transcend?”

And who really “sacrificed” them not in the real world but in the arts?

To be fair, Reich and Schoenberg do attempt to “water down” their musical transcendence with coldness and detachment. Reich’s music strictly follows the recorded voices and is devoid of explicit expression from the composer. The Schoenberg is characterized by expressionism, yet the fact that the whole piece is constructed upon a 12-tone row and an intricate plan of its transformations (inversions, retrogrades, retrograded inversions, hexachordal combinations, etc.) implies an implicit objectiveness behind the superficial expressiveness. Such efforts should be appreciated, especially compared to the overt insensitivity of John Adams’ tribute to the Sept. 11 attacks “On the Transmigration of Souls” scored for chorus, orchestra and chorus: its title suggests an obvious redemption of those who perished regardless of whether they wanted to be redeemed or not, and its use of missing persons posters as singing materials flagrantly abuses the victims as agents of expressions that build up a disturbing musical climax near the end of the piece.

But can composers as competent as Reich and Schoenberg ever achieve such a goal of rendering musical tributes to a human catastrophe?

The answer is probably no, before anyone can reconcile the need of expression and “transcendence” in music with the “barbaric” nature of such needs. Yet such musical tributes should still be welcomed as memories of those catastrophes — as long as the critics and the audience are alert to the problems and struggles within such “barbaric” music. Indeed, very few critics (including Adorno) dared challenge the aesthetics of “A Survivor from Warsaw,” and such pieces, including Reich’s “WTC 9/11,” will always, in spite of the perfectly good intention of the composers, take unconscious advantage of their content and thus practical abuse of the victims in musical criticism. Thus, there is still a long way to go before such music can ever get rid of Adorno’s label of being “barbaric.”

Comments ()