Fifth Annual Black Art Matters Festival Celebrates Artists, Poets, and Musicians

Managing Arts and Living Editor Alex Brandfonbrener ’23 discusses the fifth annual Black Art Matters festival with participating artists and performers. The event was held on Thursday, March 24, in the Powerhouse.

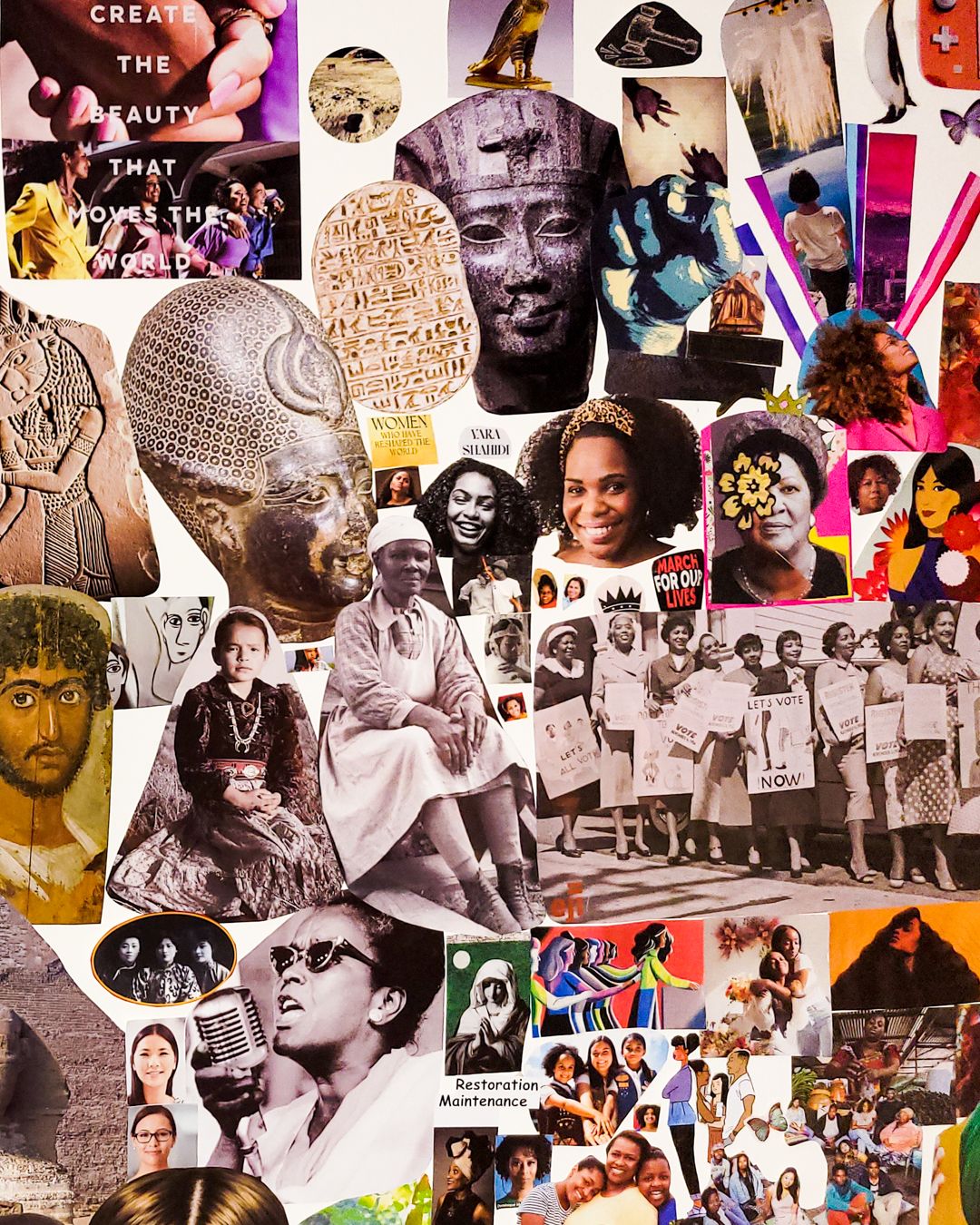

On Thursday, March 24, students filled the Powerhouse for the fifth annual Black Art Matters Festival (BAM), a celebration of the visual art, poetry, dance, and music of the college’s Black community. The festival highlighted nine student artists, who shared their artistic backgrounds and inspirations in pre-recorded interviews. These clips were projected on a big screen for attendees to watch, interspersed with remarks from hosts Kiiren Jackson ’24 and Grace Nyanchoka ’24 and live performances by student artists. The event was also live streamed.

Founded in 2018 by Zoe Akoto ’21, BAM was originally a small gathering of artists and their friends, hosted in one of the dorms on campus. Since then, the festival has expanded, and is now formally funded by the Mead Art Museum, the Multicultural Resource Center, the Black Student Union (BSU), and the Arts at Amherst Initiative.

This year’s festival was originally slated to be held in the Mead Art Museum, but was switched to the Powerhouse at the last minute due to structural issues in the Stearns Steeple, which sits right in front of the museum. As a result, the art pieces were physically absent, save for photos in the program video. The exhibition featuring the visual art pieces from the festival will reopen at a later date.

“I wasn’t particularly invested in it being in the Mead, although it was kind of unfortunate that people couldn’t see the actual artworks up close as planned,” admitted Zachary Rivers ’24E. His piece, an 8-by-8-inch woodblock print titled “Moonsight,” was inspired by a friend from UMass, who asked Rivers to make an album cover for his music. He wished attendees could have had the chance to see his print in person: “You would be able to see, ‘Oh, this is ink on a piece of paper, as opposed to it being pixels on the screen.’” But, he acknowledged, “the Powerhouse is a very good performance space. And so, for the purposes of the event, I think it actually went just fine.”

It was clear that the festival was focused on the artistic visions and perspectives of students. “[The artists] brought a sense of creativity that was experimental,” said BAM Student Coordinator Kai Ahmadu ’22. “Every single artist really gave it their all and put a lot of their spirit and personality into their work.”

Alongside Kendall Greene ’24, Ahmadu was involved with nearly every aspect of planning the event: searching for hosts from the BSU and the African and Caribbean Students Union (ACSU), securing funding for food trucks and the livestream service, and coordinating with the student artists.

Ahmadu is an artist too, and participated in the festival in 2019. His art evokes themes of sustainability and Black liberation, informed by his identity as a third-generation African from Sierra Leone. He said his background allowed him to more easily connect with artists and use the same curatorial mindset that he uses with his art to plan the festival.“I feel like when you go to a ‘Black Art Matters’ festival, you expect an open mic that might be about race relations, or you expect a painting that incorporates diasporic themes,” Ahmadu said. “But the way that [the artists] incorporated their personal lives and their unique and diverse backgrounds was pretty interesting and just special.”

One artist that resonated with him was Abadai Zoboi ’24, whose painting and dance were featured in the festival. “In the rehearsal the night before, the way she was preparing for it, I could tell that she was putting a lot of emotional intention. It kind of felt sacred, and it felt vulnerable,” he said. Ahmadu was also drawn to one of her paintings in the festival, which depicts a globe painted on a pregnant woman’s belly.

He summed up his feelings on the importance of the event: “Black art, to me, is a demonstration of Black imagination, and how Black people my age and the generations that we never got to talk to are conversing with each other in an artistic way.”

How did the artists in the festival converse artistically? I asked some artists what inspires their art, and what their art means to them.

Neviah Waldron ’24, whose piece “Floating in a Gentle Abyss” was featured in the festival, replied, “My art is inspired by nature and the elements, probably water and its movement, especially. I also love space, and I love painting the moon and planets.”

It is clear how her painting reflects her inspirations. A hand rests on the surface of bubbling, rippling water, cradling delicate pink and purple flowers in its palm. But Waldron says her art also moves beyond aesthetic beauty and iconographic motifs, taking on a personal importance: “What inspires my art the most is definitely my feelings, which change like the phases of the moon. I used to bottle up my emotions and try to will them away. But lately, I’ve been learning to channel them onto a canvas. I feel like I can express myself best this way and not feel clouded and oppressed by my feelings.”

Not all of the artists used ink-on-paper mediums for their artistic and emotional expression, however. Maëlle Sannon ’24 usually uses pencil, but pushed herself to experiment when she took “Photography I” with Conway Professor in New Media Justin Kimball. Her photo series “Maëlle in Bloom” employs similar imagery as Waldron, featuring flowers alongside self-portraits. Tight shots of her face catch the setting sun, as if she herself were a flower. The actual process of taking the photos was a little less picturesque, she admits: “I was in the middle of the soccer field, just rolling around in a bunch of dandelions, trying to capture these photos. Sports teams were going by; the whole track team was wondering, ‘What the hell is this girl doing?’ Like, in the middle of the field, one arm up holding the camera like trying to act like I’m not holding the camera. But I don’t know, it just felt very organic.”

Sannon hopes that her photos reflect her background: “Growing up in New York, having this Caribbean influence, there’s so many motifs that I carry with me, and I pull them out when I feel it’s appropriate. Flowers and bright colors: that’s something that’s very key to my Haitian heritage. And motion: that’s something that I get from New York.”

The importance of heritage was shared by Tiia McKinney ’25, whose painting “Roots” was featured in the festival. She told me that she is inspired by her Bahamian roots, as well as by racial justice movements. A formative project was one she did for her AP art class in high school: she painted Lydia McKinnon, a woman who was beaten by police during the Birmingham Campaign of 1963. Her painting in the festival drew on more recent activism:

“Over the summer, during the resurgence of Black Lives Matter, I saw so much art on my [Instagram] feed from Black creatives. The picture that I was inspired by was actually from a social media influencer, I don’t recall her name. (It was just on my ‘For you’ page, and then I screenshotted it. And after I swiped up, it was gone. So I don’t remember who the person was at this point.) But I really liked how she was sporting the durag and braids in that piece.”

The live performances were just as magnetizing as the visual art. The vibe was lively, and the audience was free to move. It was nice not being bound to chairs, especially because at intermission, there were food trucks. The free space also allowed the audience to see and approach the performers, unobstructed.

First up were two poets, Quincy Smith ’25 and Ernest Collins Jr. ’23, who gave reflective contemplations that offered moral context with a somber yet playful mood.

Smith read two pieces, titled “Ignite” and “There’s something in my throat.” He spoke confidently and played with rhythms. It was fun and emotional. I liked the start of his second piece: “The little boy ran, until his knees cracked under him. Other little black boys screamed metal at his eyes. The ground / shook with pressure…” The Student published his first piece on March 9, which you can find here.

Collins also read two pieces, the first of which stuck out to me sharply: “Ferguson is burning, like they said London Bridge’s falling / A game not so appalling, but y’know what galling? / Another black kid is dead…” It was an impactful performance, well executed and spoken with clear intent.

The festival also featured musical artists like Stanley Jackson ’25, who rapped an original piece titled “Sicker Than You.” His motivations were simply stated: “I really like rap music, of course, and R&B, too. I listen to all types of stuff … like Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole, Chance the Rapper, and Smino. [My music] is basically just my life experiences, anything that comes to me as I’m living.” He shared that the inspiration for “Sicker Than You” was equally simple: “I was bored one day.”

His performance, conversely, was smooth and confident. Jackson fluently flew through bars with precise diction and creative rhythms, even though the festival was only his second live performance ever. The first was at the BSU Black Harlem Renaissance event in 2018, the year Jackson originally started at Amherst as a first-year. This time, “I was very nervous before I got on stage,” he said. “But once the music started, it kind of went away. There were more people at this thing than who were at the [BSU event], though I do think I did a better job this time.”

Rounding out the musical performances in the festival were singer Joseph-Jerome Raymond ’24 and guitarist Gregory Smith ’24. They played four songs, including a mash-up of Stevie Wonder’s “Isn’t She Lovely” and Grover Washington Jr’s “Just the Two of Us,” as well as two of Raymond’s original songs from a new EP. Both musicians accentuated groovy, wistful vibes with improvisational rhythms.

I asked Raymond about his songwriting, which he said he only started during the pandemic, noting that it was then that he found time to slow and process his art, and examine what is important to him. “I love telling stories, and accounts of my past always find their way into my music,” he continued. “But recently, I’ve found that I can also [write about] things I’ve yet to experience, or things I yearn to experience. I started writing about love before I even found love. I started contemplating loss before ever experiencing it.”

Raymond also shared a list of artists who have inspired him “for their voices, candor, and creativity: Ari Lennox, SZA, Brandy, Rihanna, Miguel, Lucky Daye, Summer Walker.” He also said that they stand out to him because these are “artists that choose to make music for themselves, [and] that’s how I think it’s supposed to be.”

The festival closed with a performance by members of Dance and Step at Amherst College (DASAC), a lively step routine to Bankroll Freddie and Megan Thee Stallion’s “Pop It” that captured the celebratory feel of the event. Ahmadu noted that the unified feeling of the festival was especially remarkable, that Black people from vastly different cultures — from the Caribbean, from Brazil, from Ghana, from South Carolina, and more — could so deeply connect with each other through art: “Their voices and the diversity of their backgrounds pulled together into a mosaic” — a piece of art in itself.

In an effort to further support Black student artists at Amherst College, The Student is providing the social media links of all students interviewed for this article:

Zachary Rivers ’24E: @zach.rivers.art (Instagram)

Kai Ahmadu ’22: @chi.creates (Instagram)

Stanley Jackson ’25: @s.i.k. jackson (Soundcloud)

Joseph-Jerome Raymond ’24: J. Jerome (Spotify)

Gregory Smith ’24: Gregory R. Smith III (Spotify)

Comments ()