From Eggshells to Energy: Tracking the College’s Compost

The college produces a staggering amount of food waste which, thanks to a new contract, is processed by Vanguard Renewables into low-carbon fertilizer and renewable natural gas. The new composting program is part of a broader reassessment of food systems and food waste at the college.

A peach pit, a crushed eggshell you couldn’t quite peel off in one go. A teabag, the cod cake you tried, but didn’t like. Your disposable fork, the empty packet once filled with sugar. This smattering of items is a sample of what’s left after a meal in Valentine Dining Hall (Val) — and all of it goes to the same destination: the compost bin.

The college produces a staggering amount of organic food waste which, thanks to a new contract this year, is sent to Vanguard Renewables, a company that processes the waste into low-carbon fertilizer and renewable natural gas. The new composting program is also part of a broader conversation about food systems and food waste at the college.

Most of what we consume in Val, including packaging and disposable ware, is compostable. Anything that’s not is from outside producers: soy sauce packets, chip bags, and ice cream bar wrappers, to name a few.

This means that every year, Amherst College produces around 50 tons of compost — that’s 100,000 pounds — according to Executive Director of Dining Services Joe Flueckiger.

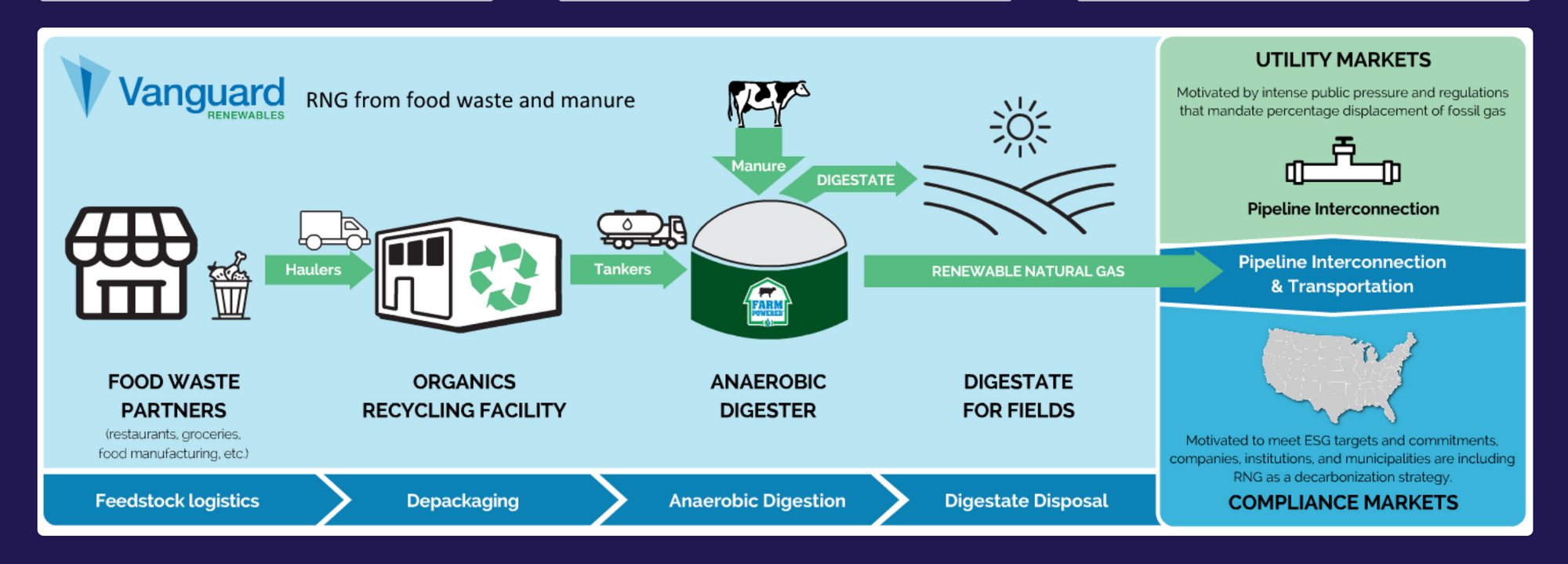

When a piece of waste goes into one of the compost bins on campus, it’s compiled in a compactor at Val. From there, it’s transported to a nearby facility run by Vanguard Renewables. There, Amherst’s organic waste will mingle with cow manure in an anaerobic digester, and become three different products: low-carbon liquid fertilizer, solid bedding for cows, and pipeline-quality methane natural gas.

But let’s back up.

Compost, Carbon, and Cows

Composting is a process in which food waste and other organic matter is kept under certain conditions, and eventually breaks down through microbial activity. What’s left is rich, soil-like fertilizer that contains all of the nutrients from the organic material. These nutrients play the same role as synthetic plant fertilizers in supporting plant growth, but they also go above and beyond in feeding healthy soil conditions with abundant nutrients.

“The way I think about it is just as sort of a model system for understanding decomposition,” said Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Rebecca Hewitt. “It’s this important mechanism for reducing the negative impacts of food waste … by allowing the nutrients and the carbon in the food to be feeding the soil.”

In the past, Amherst trucked its food waste to Martin’s Farm, a business in Greenfield that uses a large-scale manual process to make and sell compost. There, organic material is mixed and ground by machine, and then carefully monitored, turned, screened, and cured to make a final product. The process works well to produce useful compost to sell to farmers.

However, Flueckiger said his office came across “a number of reports” containing findings about some of the drawbacks of large-scale composting. While Flueckiger made clear that the problems were not related to Martin’s Farm specifically, that style of large-scale composting has reportedly caused contamination in land and water areas.

While exploring further options this past summer, the college was approached by Vanguard, and made the choice to contract with them instead of Martin’s Farm. The switch was decided upon by Flueckiger, along with staff from Landscaping and Grounds, Campus Operations, and the Office of Sustainability.

Vanguard engages in what they call “organics-to-renewable energy projects,” which are different from conventional composting. The company’s goal is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from food waste and recycle the waste into “a powerful source of renewable energy and low-carbon fertilizer.”

Here’s what that means. As any pile of decomposing organic matter breaks down, it emits greenhouse gases, gases that trap heat in earth’s atmosphere, leading to global warming. The Environmental Protection Agency has estimated that each year U.S. food waste accounts for 170 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions — about equal to the annual emissions from 42 coal plants.

That doesn’t even include annual emissions of methane gas from waste, which is more potent, and a major emission from landfills — 15 percent of all U.S. methane emissions comes from landfills.

In the case of a landfill, not only do greenhouse gases get emitted, the matter itself goes to waste, and much of it does not ever decompose. Compost provides a better alternative to this setup, in which some emissions do occur, but the product can be reused in sustainable agriculture, replacing synthetic fertilizers that have heavy carbon footprints of their own.

Vanguard takes this process a step further by not only reusing the organic product, but also capturing the methane emissions, and purifying them into pipeline-quality methane gas — what has been coined “renewable natural gas” (RNG) — which has a smaller carbon footprint than conventional natural gas obtained from below-ground source.

The Vanguard Way

At Vanguard facilities, the organic food waste is heated to 108 degrees Fahrenheit for five days, and then mixed with cow manure from their dairy farms in an anaerobic digester. Anaerobic digestion is the process by which microorganisms, in the absence of oxygen, decompose organic waste. This process naturally releases biogas. In Vanguard’s digesters, this biogas is contained by a rubber membrane, allowing it to be collected, extracted, and purified into natural gas. It can then enter existing infrastructure and be used to power electricity.

The remaining liquid is then sold as fertilizer for crops, replacing chemical fertilizer. The solids become bedding for the cows on dairy farms.

“It’s super exciting to be able to utilize that [biogas] in a way that we would just be lost otherwise, and that is what’s happening in other types of composting,” said Flueckiger, who visited the facility with Director of Landscaping and Grounds Kenny Lauzier over the summer. He described what he saw as “amazing.”

“Typically, natural gas is something that you have to get from fossil fuel extraction,” said Director of Sustainability Wes Dripps, “and so in our efforts to minimize the impacts of … fracking, which has all kinds of negative effects, this provides a mechanism where we’re … generating renewable natural gas that then can be used and burned just like any other natural gas for energy.”

According to its website, thus far, Vanguard has generated enough electricity with its RNG to power 7,268 homes.

The company has taken off in recent years — this past summer, it was acquired by the investment company BlackRock, which has itself come under criticism for its investment in the fossil fuel industry and companies that engage in deforestation. Vanguard has also taken the lead on the Farm Powered Strategic Alliance (FPSA), which includes groups like Unilever, Starbucks, Chobani, and Dairy Farmers of America, and aims to reduce food waste and recycle remaining waste into renewable energy production.

While the combustion of natural gas required to produce electricity still emits greenhouse gases, Hewitt said “a lot of people talk about natural gas as a bridge fossil fuel” on the way to a renewable energy future, because its emissions are still lower than coal and oil. Vanguard’s approach finds a renewable, less ecosystem-damaging source for that gas while our infrastructure still relies on it — as Dripps mentioned, fracking, the process of extracting natural gas from underground, has well-documented catastrophic environmental and health effects.

“You’re using … the methane [emissions],” Hewitt said, “Either that’s gonna get used as a fuel source or it’s not.”

Dripps shared information that Vanguard sent to the college about their first quarter contracting with the company. In that time period, the college recycled 15 tons of organic waste and produced fertilizer for an acre of land. According to Vanguard, the greenhouse gas emissions mitigation is equivalent to 142 trees being planted. Amherst’s average continued contributions will likely be even higher than this, since the data was from an incomplete first quarter and accounts for summer months with less activity at the college.

Food Systems, Waste, and Sustainability

The college’s composting protocol fits into a larger continuing conversation about our food system and the waste it produces. Student groups like the Food Justice Alliance (FJA) and Sustainable Solutions Lab have continually addressed this topic, and Dripps says it is one of the main issues that community members bring up to him as the director of sustainability. Perhaps most notably, this year’s brand-new Food Systems Committee has brought together stakeholders from around the community to work on issues related to the college’s food system.

Food waste, in particular, is a highly relevant issue in both a local and national context. In the U.S., 40 percent of all food produced is wasted. “[Food waste] plays into all of the major issues: climate change, food insecurity, issues around diversity and privilege, labor relations, poverty,” said Flueckiger. “There's just a multitude of concerns.”

So while composting is a beneficial solution, these various campus offices have maintained their focus on reducing food waste overall.

“The sustainability scientist in me would say, ‘I think compost is an integral part of the solution,’” Dripps said, “but … you back up and look at the whole system and ask, ‘why are we generating so much food waste?” If we didn’t do that, we wouldn’t have to worry about composting.’”

Of course, some food waste is unavoidable — according to Flueckiger, 30 percent of the college’s food waste is prep waste, such as inedible stems and peels of vegetables — and that’s why being proactive about composting is important. But, as Dripps put it, “the easiest waste to figure out how to repurpose is the waste you don’t generate.”

The other 70 percent of food waste comes from what is thrown away after the meal. A program piloted by FJA last year has worked with existing programs at Val to donate untouched leftovers from our meals to local organizations. According to Flueckiger, though, plate waste accounts for much of the college’s waste footprint.

Beyond food leftovers, the biggest obstacle to reducing our waste is the abundance of single-use products used for to-go dining. Val currently goes through about 1,000 single-use to-go containers per day.

“It’s killing me to see,” said Flueckiger, “The expense is really not the part that bugs me as much. It’s more about how much more material we’re putting into the waste stream.”

The green plastic to-go containers that were used during the 2020-2021 academic year, as well as in the fall of 2021, attempted to create a solution to this problem, as they could be washed and reused. But Flueckiger recalls these as “a miserable failure” because a large portion of them ended up in the trash, despite efforts to clarify that they could be returned and recycled.

The culture of to-go dining has created problems for composting, too. “It’s created a back-stream issue of … collect[ing] residential compost in an effective, efficient way that doesn’t create a hot mess for the custodial staff, doesn’t smell, doesn’t have bugs,” said Dripps. “And we don’t have an answer for that yet.”

Plus, he added, much of the food that gets taken out of Val doesn’t end up in the compost anyway. A recent waste audit of the first-year quad done by seniors in the environmental studies department found that about 43 percent of the waste in the garbage bins should have been in the compost.

“If we don’t generate [waste] on the front end, we don’t need to worry about people source-separating and knowing what goes to the landfill and what goes to recycling,” Dripps said. “Despite all our education efforts, if it all comes down to every individual having to follow all the rules, that’s just not a recipe for success. It needs to be, ‘How do we systematically address it on the front end?’”

The single-use products used for our to-go options — including the containers, cutlery, and cups — are all compostable. This softens the blow of the waste, but Dripps cautioned that people shouldn’t become “complacent” in saying “‘Don’t worry, it’s compostable.’”

In reality, this compostable ware will not decompose on its own in just any compost bin — let alone a landfill, if it’s accidentally put in the trash. The pieces require industrial-level processing, which grinds them in order to let them truly decompose. Both Martin’s Farm and Vanguard provided that option to the college, but that necessity emphasizes the “asterisk” that comes with the “compostable” label.

A New Mode of Decision-Making

The question of how to reduce food waste and make our food system more sustainable is a big one. The new Food Systems Committee is attempting to address it by bringing in people from all over the community.

“I think the goal with trying to have an overall Food Systems Committee was to branch out from just dining and also include more stakeholders and more people who are impacted by the food system,” said Willoughby Carlo, green dean in the Office of Sustainability.

Carlo has headed the development of the committee, which was ideated last semester by former Sustainability Office Fellow Parker Richardson ’22. It now includes representatives from Dining Services, including Flueckiger, dining staff, and chefs, as well as representatives from the broader student body and AAS, Office of Sustainability staff and student fellows, staff and faculty, and representatives from Book and Plow Farm.

In Flueckiger’s words, “The major discussion [in the Food Systems Committee] has been about, how can we divert some of our purchasing power to more sustainable choices?"

Together, the committee is focusing on a range of topics related to our food system, including waste and composting, but also energy usage, a greater reliance on local food, affordability and accessibility, culturally appropriate foods, and more.

“When you set aspirations for carbon neutrality, you have to address all the different sources,” Dripps said, “[the Food Systems Committee] provides a better forum to [discuss] these kinds of systemic questions about, how we, as a campus, can move ourselves to increasingly more sustainable systems.”

Comments ()