From Memorial Field to the MLB — Alumni Profile, Dave Jauss ’80

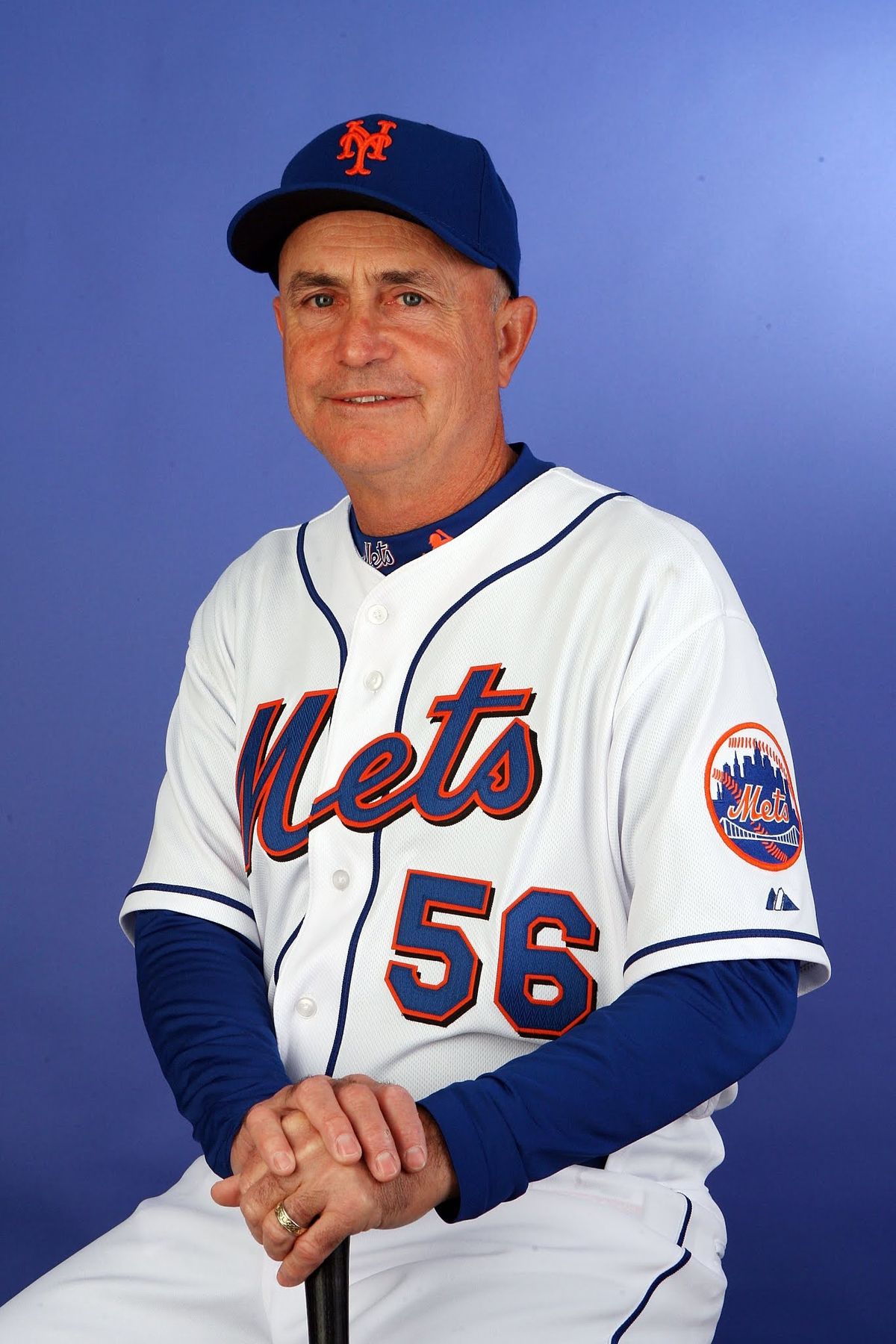

After starting his career as an assistant coach at Amherst, Dave Jauss ’80 spent over two decades coaching Major League Baseball.

By the evening of July 12, 2021, Dave Jauss ’80 had spent over two decades coaching Major League Baseball while still remaining relatively anonymous within the sport’s fandom. That day, however, his breathtaking performance pitching Mets first baseman Pete Alonso to victory in the MLB Home Run Derby initiated a viral mania among hardcore baseball fans shocked at the theoretically easy, and yet almost unheard of, accuracy of Jauss’ practice pitches. This fame spawned a New York Times profile revealing his slightly alarming addiction to black coffee and, as expected when one suddenly takes the sporting world by storm, an interview on the “Pardon My Take” podcast, which he describes as the pinnacle of his “48 hours of fame.”

The Home Run Derby may seem like a trivial event for which to gain fame in comparison to the 30-plus years Jauss has spent coaching professional baseball. All his job entailed, after all, was throwing practice pitches that Alonso could smash 500 feet into the Denver sky. Yet, in a way, the event encapsulates what Jauss describes as the most fundamentally important aspect of coaching: earning an athlete’s trust by getting them to “know that you care.” So, as he delivered strike after strike to Alonso on that cool summer night three years ago, it turns out Jauss was actually revealing the secret to his long, rewarding career. A career that started, improbably enough, right here at Amherst.

From the Midwest to Memorial Field

Jauss’ journey to Western Massachusetts might seem surprising to current students. A Chicago native, neither he nor anyone in his family had ever heard of Amherst before he arrived. Growing up blocks away from the Northwestern campus, a school his dad Bill Jauss covered as a sportswriter for the Chicago Tribune, Jauss was raised a Wildcats fan. Jauss still attributes his love of baseball to long car rides with his dad’s group of sportswriter friends, which he claims was the inspiration for SNL’s “Bill Swerski’s Super Fans.” This infatuation with the sport eventually led Jauss to pursue the game throughout high school, and when it came time to pick a college, he focused his search on schools where he could continue to pursue his passion.

However, playing Division 1 at Northwestern was beginning to look unlikely. “I was a really bad player, but I could play defense,” Jauss said. While his hitting may have been poor enough to get “DH’d as a position player” — the practice of having another player hit on his behalf — his impressive fielding skills led Northwestern’s coach to contact legendary Amherst baseball coach Bill Thurston, who thought Jauss had serious potential at the Division 3 level and brought him in “site unseen” as Amherst’s starting shortstop.

At Amherst, Jauss admits he felt something like a “square peg in a round hole.” While he initially planned to study math and, eventually, become a teacher, Jauss remembers Professor Norton Starr of the math department approaching him halfway through his first semester to gently explain he “had no chance" in the subject.

“I wasn’t very good at statistics, but it was a very good statistical realization … I said, ‘I’m going to find a major that fits my brain and doesn’t put me in a position to not graduate,’” Jauss said. That major ended up being psychology.

Although he likes to joke that “I can’t remember anything I learned in those classes,” Jauss admits that he feels as though the psychology degree is “ingrained in me” somehow. Specifically, he feels as though the degree influenced him in “teaching my ideas about training, coaching, and developing players and teams.”

Of course, it was not just in the classroom at Amherst, but also on the field and court that Jauss learned valuable lessons about coaching. In addition to being a 4-year member of the baseball team, Jauss walked onto the varsity basketball team his senior year, where he was one of the first players to be coached by future Hall of Famer Dave Hixon.

Jauss reflected on his coaches’ impact, “When I was there on the field, I probably played better than I should have because I knew the game and played the game right, and knew what to do to succeed and have our team succeed.”

It was Thurston and Hixon who implanted in Jauss the guiding principles for the rest of his career. “You first have to make sure that players know you care. And secondly, you have to know they trust you. And until you have those two things, it doesn’t matter what you know or how you can teach,” he said.

Outside of the field and classroom, Jauss kept himself busy as a member of the Delta Upsilon (DU) fraternity, a group that he suspects “was the reason fraternities got closed down.”

He spent most of his time at Amherst as a resident of the DU fraternity house, the modern-day Porter House. At DU, Jauss fondly recalls designing a homemade 6-hole golf course in their backyard and pranking other students with “Prince Al,” the Prince of Monaco.

Throughout his time at Amherst, as part of sports teams and as a member of DU, Jauss made lifelong connections that he still cherishes.

“The friendships I made and what I learned from those friendships while I was there has really molded me into the man I am today,” he said. “If you're 67 years old, and you can call up 40 to 50 guys three times a year that you went to school with, you'll have a good network.”

“Trying to teach P.E.”

Jauss is notably self-effacing about his decision to pursue coaching as a career. While the Amherst baseball team was talented enough his senior year to have eight team members sign professional contracts after graduation, Jauss was one of the few who had to see their playing careers come to a close.

“That’s the reason, actually, why I went into coaching,” he said. “Those who can’t play, teach, those who can’t teach, teach P.E, so I went and tried to teach P.E.”

Yet, since he lacked a teaching degree, Jauss found himself out of a job. Taking the advice of his old basketball coach, Dave Hixon, Jauss applied for the Hitchcock Fellowship at Amherst College, allowing him to pursue a sports management degree at UMass Amherst while he served as an assistant coach for the Amherst football, basketball, and baseball teams. To make ends meet, Jauss simultaneously helped a college friend start a construction company in Boston, which necessitated a two hour commute both ways to his coaching job.

Jauss continued to work at the collegiate level for a number of years, including time spent as the head baseball coach at Westfield State and Atlanta Christian College. Eventually, he landed his big break into professional coaching in 1987 when he was hired as manager of the Gulf Coast Expos, a minor league team in Palm Beach, Florida. One of his early tasks was to catch practice pitches for the team’s relievers, that is, until “Randy Johnson threw a ball over my head that hit the chain link fence behind me and I said, ‘we need to get two catchers down here so that I don’t get killed.’”

After a decade in the minors, Jauss became the first base coach for the Boston Red Sox in 1997 and, in his own words, “hasn’t missed a big league training camp since.” Funnily enough, Jauss claims the skill that first got him hired into the Major Leagues was his robotic accuracy while pitching BP — the very same skill that made him an overnight sensation following the 2021 Home Run Derby.

For most of his twenty-year career in the major leagues, Jauss served as a bench coach for various franchises, including the Red Sox, Los Angeles Dodgers, Baltimore Orioles, and New York Mets. He also earned a ring for the Red Sox as a scout when they triumphed in the 2004 World Series.

Jauss, who described the bench coach position as “what in every other sport they would call assistant coach,” noted that the most important aspect of his job was to fill the gaps in his manager’s coaching arsenal.

“I believe the best bench coaches realize that as strong as the manager is in his overall game, there are still some things he’s not as strong at," he said. "The best bench coaches need to bring a wide spectrum of abilities to make sure that you combine to complement each other.”

Not your typical coach

Despite Jauss’ lifelong association with baseball and Amherst’s impressive resume of graduates serving in MLB front offices, Jauss feels that his position at the top of the baseball coaching world was an unlikely one.

“There were only, like, three of us that hadn’t played professional baseball that were coaching when I entered in a job in ’87,” he said. “A lot of people railroaded me to try to become another GM [General Manager] … but I went into coaching because I loved being on the field, in uniform, in the spikes, so I stayed that route.”

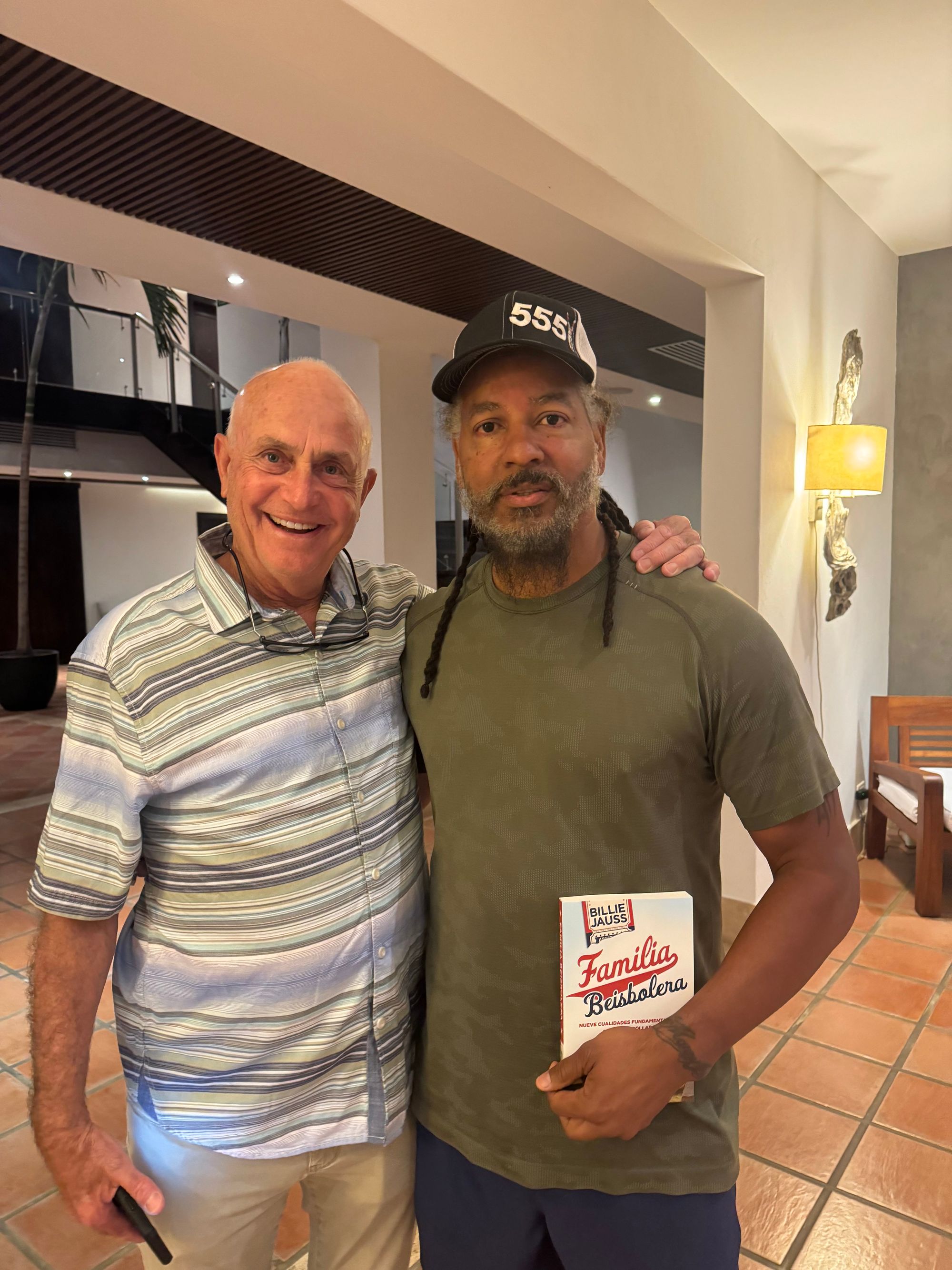

That route has been a long and winding one, taking him all the way from Memorial Field to Major League dugouts. Throughout it all, Jauss has been guided by his deep-seated love for the game of baseball and the people in it. “By far and away, the most impactful thing in my life since 1980 and being in baseball is the relationships I've got,” he said. When pressed to give a favorite baseball memory, Jauss does not mention Home Run Derbies or World Series titles, but instead, he mentions the time early in his career he spent coaching Winter League baseball in the Dominican Republic. “It’s just … there’s such a baseball fanaticism over there, and people love it,” he said. “Every day is a playoff game, and there’s nothing like it.”

While he no longer serves in a coaching position, Jauss still remains involved with the game as a Senior Advisor for the Washington Nationals. Upon being asked whether he would ever consider a return to coach the Amherst baseball team, Jauss did not offer a complete denial — but he thinks head baseball coach J.P. Pyne is doing a “really good job.”

“I like him, and guess what, he’s not a typical Amherst guy either. So I like that. I like guys that aren’t typical Amherst guys,” he said. What more could be expected from Jauss, a baseball coach’s baseball coach. Truly, in his own words, “a rare breed.”

Comments ()