Old News: Five Historic Election Days on Campus

From widespread protests in 1968 to raucous celebrations in 2008, this Election Day edition of Old News explores how The Student reported on five different elections across three centuries.

On the night of Nov. 5, 1912, Amherst students gathered in College Hall, now home to the Loeb Center, to receive the returns of that year’s presidential election, which was waged among four major candidates: incumbent Republican William Howard Taft, Democrat Woodrow Wilson, former President Theodore Roosevelt, and Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs. Between the hours of 9 p.m. and midnight, students enjoyed “good smokes and refreshments” from the faculty and music from the college band. Throughout the night, two senior students updated large bulletin boards with the ongoing results.

The scene doesn’t sound too far off from the events planned to take place on Nov. 5, 2024, in Keefe Campus Center, where students will gather to watch the election results as they roll in. There will be some key differences: it’s doubtful that any faculty will provide students with “smokes,” for example, and 1912’s Amherst did not provide 24-hour counseling center support in anticipation of high election anxiety. But the college will serve “refreshments” — Late Night Dining in Keefe — and students will view the results on a continuously updating map in the Atrium.

This week’s Old News is special — instead of using a random number generator to pick a year, I did some hand-selection, poring over Student editions from a variety of election years: 2008, 2000, 1968, 1932, and 1868.

2008

The editions of The Student surrounding former President Barack Obama’s victory in 2008 describe a campus full of passionate engagement and raucous joy.

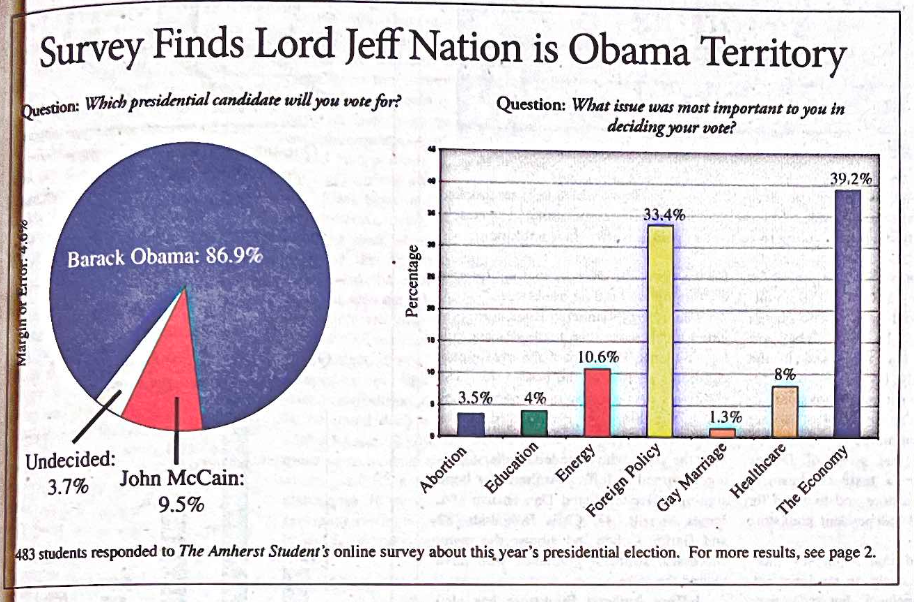

On Oct. 29, 2008, The Student reported that Amherst was solidly “Obama territory.” Just shy of a week away from that year’s election, 86.9% of Amherst students said they were voting for Obama, 9.5% were voting for Republican nominee Senator John McCain, and 3.7% were still undecided. In the midst of the 2008 financial crisis and the Iraq war, students said the issues most important to them that year were the economy and foreign policy.

On the op-ed pages, one student wrote that while “despite polls projecting a substantial Obama lead … many pundits are afraid that Obama will suffer from a late-game collapse due to latent prejudices of white voters.”

Another writer lavished praise on McCain, calling him a “superior candidate … done in by biased media.” He claimed that Obama was inexperienced, and McCain’s running mate former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin had faced “slander and sexism in the media.”

The next week, after Obama’s victory, The Student proclaimed “OBAMAMANIA Hits Amherst” in an article that captures a campus in joyful celebration — evidence of his majority support among students.

When the election was called for Obama around 11 p.m., festivities “simultaneously erupted” on the First-Year Quad and the Social Quad (near the old Social Dorms, where the Science Center is now). Students, including “a mob of euphoric first-years[s]” ran around campus from celebration to celebration, popping bottles of champagne and singing Obama’s campaign song, “Signed, Sealed, Delivered” by Stevie Wonder. On the First-Year Quad, the Zumbyes led the crowd in singing the national anthem.

Ariana Robey-Lawrence ’12 was at a watch party in Drew House, where the crowd chanted Obama’s campaign slogan, “Yes we can!” as they poured out of the dorm to join the celebration.

“I planned to head back to my dorm, but I spotted a line of people … heading to Keefe,” Robey-Lawrence said, “Some people had taken trash cans and were using them as drums, while others started dancing and chanting … I left my dorm at about 11 p.m. and returned at 2 a.m. Undoubtedly one of the best nights of my life.”

Simon Gao ’12 didn’t even put on shoes, too excited to join the crowds. “I was running on air even just wearing a soaked pair of socks,” he wrote, “I hugged, high-fived and conversed with complete strangers … It made me feel more a part of the College than anything in the two months I’ve been here.”

“I’ve never seen anything like it — not even an Amherst win over Williams or the Red Sox winning the World Series,” said Josh Nathan ’10, “It felt like the world had erupted in a cathartic upswell of emotion after eight long, terrible years.”

“When I watched Obama’s speech, I was particularly struck by his statement that his campaign ‘grew strength from the young people who rejected the myth of their generation’s apathy,’” Nathan continued, “In the last eight years [of the Bush administration] … I have felt … oppressed by a pessimism and a cynicism born of the belief that my government does not reflect my values or views. Tuesday night, for the first time in recent memory, I was proud to be an American.”

While it otherwise captured the excitement of the night, The Student’s coverage did not mention the historic nature of Obama’s election as the first Black president.

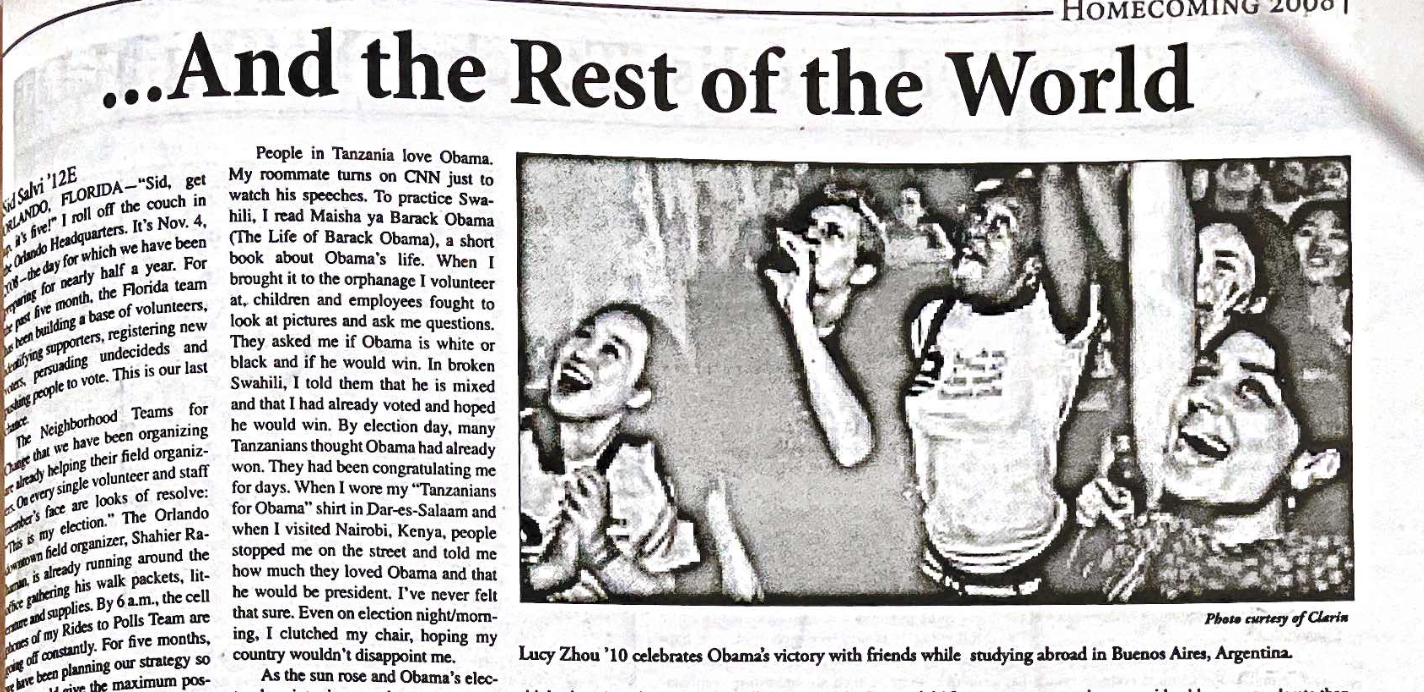

The Student also included dispatches from students studying abroad in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania; Buenos Aires, Argentina; and Göttingen, Germany, who found festivities abroad.

Megan Zapanta ’10 wrote of the support for Obama that she saw in Tanzania and Kenya. “The world is demanding social change, and believes that Obama will bring it … I only hope he can live up to the expectations,” she wrote.

Especially significant was a report from Sid Salvi ’12E, who had taken the semester off to work for Obama’s campaign in Florida. Salvi described an Election Day packed with get-out-the-vote efforts, driving countless voters to the polls.

At 11 p.m., “pandemonium,” Salvi chronicled: “People run around downtown Orlando screaming ‘Yes we did’ … Complete strangers hug each other.”

2000

Eight years earlier in 2000, The Student never got to report on the winner of the election. By the time that Al Gore conceded to George W. Bush on Dec. 13, 2000, it was winter break. The Student would not resume publishing till the next semester, when Bush had already been inaugurated.

But the Nov. 2000 issues of The Student catalog a campus waiting for results alongside the rest of the country. On election night, Nov. 7, 2000, there was no confirmed winner — it quickly became clear that the result came down to Florida, where Bush led by fewer than 600 votes, triggering a recount. In the month following, multiple recounts yielded numbers showing Bush’s lead at just 154 votes. On Dec. 12, in a 5-4 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Florida Supreme Court’s decision mandating a recount. The recount was stopped, and the presidency went to Bush, eked out by only one electoral vote. Gore won the popular vote, however, making 2000 the first election since 1888 with mismatched popular and electoral results — it would be followed, of course, by 2016, when former President Donald Trump won the presidency despite losing the popular vote.

The Student reported on the Florida recounts in the issues following Election Day. In the opinion pages, students offered different perspectives on the situation.

“Don’t Cheat Gore Out of the Presidency,” read the headline of one piece by Adam Nagorski ’02, who argued that confusing “butterfly ballots” in Palm Beach County meant a plethora of votes were mistakenly cast for Independent candidate Pat Buchanan.

He deplored the Bush campaign’s attempts to block a recount saying, “To oppose the most accurate count possible is tremendously ignoble.”

Nagorski went a step further, decrying the “outdated electoral college.” “Should Floridians’ votes really be worth over 800 times more than votes cast elsewhere?” he asked. He pointed out that Hillary Clinton, then a newly elected senator from New York, had promised that abolishing the Electoral College would be her first act in the Senate.

Meanwhile, Windy Booher ’02 wrote “Something Rotten In the State of Florida,” disagreeing with Nagorski’s argument. “It is … possible that people misread the ballot [in Palm Beach County],” she wrote, “Well, that’s their own damn fault … Voting is a precious privilege in this country, and if you really value your vote, you’ll cast it carefully.”

“We cannot continue to recount until we are happy,” she said. “At this point, either man’s administration will be tainted with the scent of illegitimacy.”

1968

It’s difficult to ignore the similarities between the 1968 election and 2024’s. Joe Biden’s July decision to step out of the race was reminiscent of March 1968, when then-President Lyndon B. Johnson announced mid-primary that he would not seek reelection. His vice president, Hubert Humphrey, became the Democratic nominee, facing Republican candidate Richard Nixon.

The election took place in the context of national turmoil. In April, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and in June, Robert F. Kennedy met the same fate. Before he was killed, Kennedy joined Eugene McCarthy in challenging Humphrey for the Democratic nomination. Both candidates, but particularly McCarthy, took Humphrey to task for the Johnson administration’s record on the Vietnam War. As in 2024, student protests against the U.S.-backed war abroad defined campus life in 1968 and escalated into election season, including at Amherst.

On Nov. 4, The Student reported on a poll taken from the student body, which was then all-male. Humphrey received “surprising backing,” with 58% of student support. Twenty-one percent of students voted for other candidates or abstained, with 19% in support of Nixon, and 3% in support of segregationist independent George Wallace. The write-ins included 25 votes for McCarthy. Men in fraternities chose Nixon or Wallace twice as much as non-fraternity students — who chose independent candidates twice as frequently as fraternity brothers.

In the leadup to the election on Nov. 5, The Student reported that a dean of the college, Nathaniel Reed, organized a Nixon rally on the town common, where the Zumbyes performed. Other Amherst students gathered to boo them, chanting “You’ve seen one Zumbye, you’ve seen ’em all.”

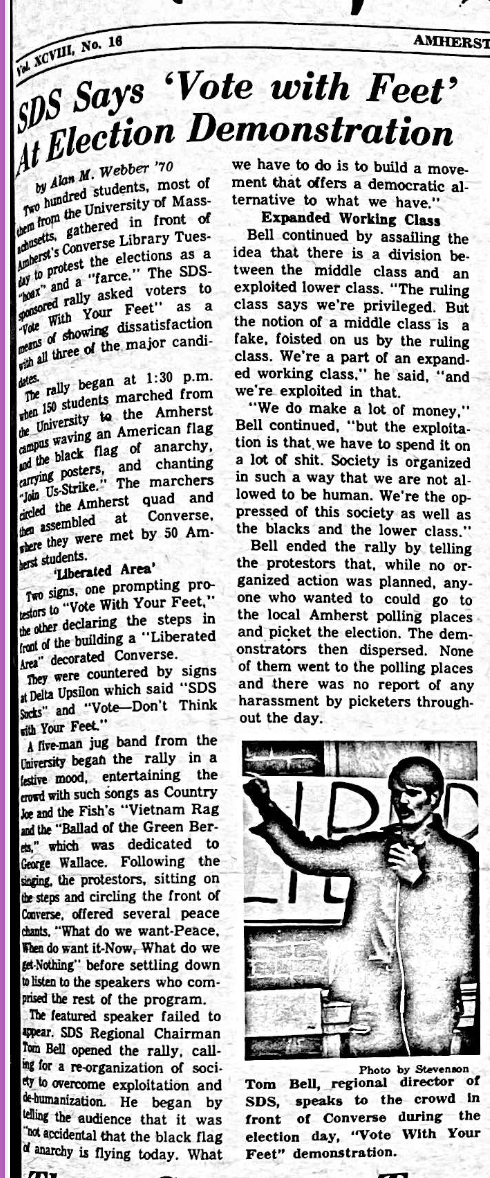

On Election Day, Amherst’s chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) held a “Vote With Your Feet” rally and teach-in to protest the election, which they saw as “a meaningless ritual to make us think we are making important decisions.”

“The SDS release urged all people not to submit to the anti-democratic political-economic structure of America” by voting, The Student reported.

Amherst SDS also published an excerpt from the Boston SDS newspaper “Old Mole” formatted as an exam that asked readers questions like: “Which of the following [candidates] have voted against military appropriations bills for the Vietnam War at some time in their political careers?” The answer was “None of the above.”

On Election Day, 150 students marched from University of Massachusetts, Amherst with American and anarchist flags, joining about 50 Amherst students in front of Converse Hall — which they marked as a “liberated area” — to protest the elections. At the rally, a band played and students led peace chants.

While a planned featured speaker from the Draft Resistance Group did not appear, the SDS Regional Chairman Tom Bell opened the rally by saying it was “Not accidental that the black flag of anarchy is flying today. What we have to do is to build a movement that offers a democratic alternative between what we have.” Bell told students that they could go picket the election at polling sites, but The Student reported that no rally attendees did so.

Counterprotesters from Delta Upsilon faced the rally with signs reading “SDS Sucks” and “Vote — Don’t Think with Your Feet.”

In the end, Nixon won. The Student said that students were generally “unhappy” and “dissatisfied” with the results and remained “fairly somber during the evening.” There were watch parties for Democratic and Republican students. At Phi Gamma, “a bastion of Nixon strength,” the Young Republicans rented three color TV sets. While few stayed up to see the final returns come in, “the party closed early with the Young Republicans confident … It was rumored that a Nixon defeat could have resulted in a glue sniffing orgy.”

Robert S. Nathan ’71 wrote an op-ed titled “Knot in My Stomach.” “Some of us tried … with Hubert Humphrey; some thought he was the lesser of two evils, others that he was the right man all along,” Nathan wrote, “Richard Nixon may indeed wreak havoc on the welfare system of this country … My fear lies in simple things that we have taken for granted — things like the federal backing of [S]outhern school desegregation.”

“There is a knot in the bottom of my stomach. I don’t want it to take eight years to untie it … I’m hoping I’m very wrong. But I think I’m very right, and I know I’m very scared.”

1932

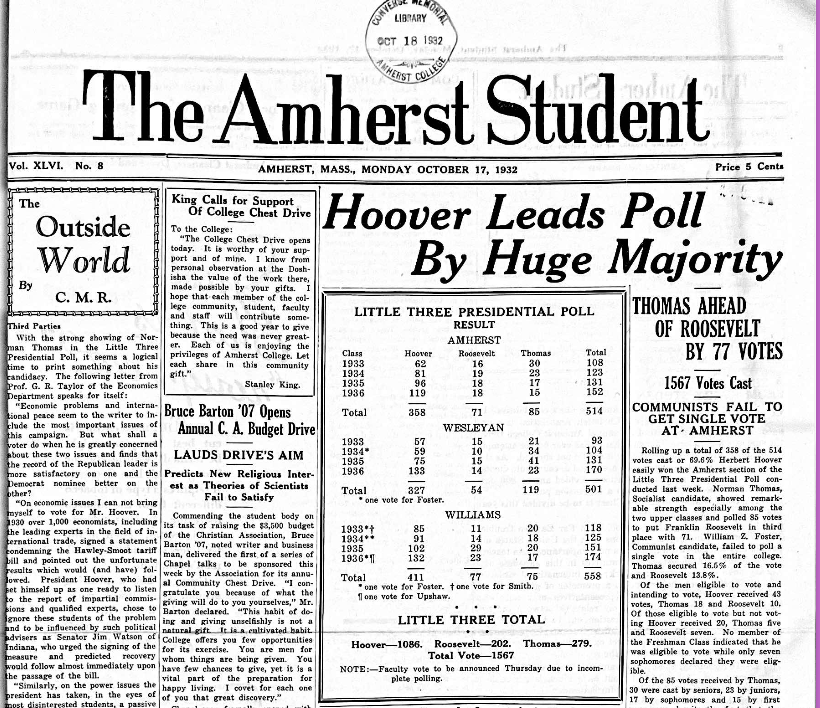

In the midst of the Great Depression, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the presidency by a landslide, in what would be the first of his three terms. At Amherst, though, he received marginal support. “Hoover Leads Poll By Huge Majority,” The Student reported on Oct. 17, 1932, publishing poll results from Amherst, Wesleyan University, and Williams College. Then-President Herbert Hoover won at all three schools — at Amherst, with 70% of the student vote. Socialist candidate Norman Thomas beat Roosevelt by 77 votes, and The Student reported that “communists fail[ed] to get a single vote at Amherst.”

Professor of Economics G.R. Taylor wrote a letter in the paper voicing that on economic issues, he “[could not] bring [him]self to vote for Mr. Hoover,” who was president during the 1929 stock market crash. “But on questions of foreign policy,” he wrote, he preferred Hoover to Roosevelt, whose “record does not inspire confidence,” citing Roosevelt’s involvement in the “unfortunate” American occupation of Haiti and his “repudiation” of the League of Nations.

A student columnist who identified themselves at C.M.R. wrote on Nov. 14, after Roosevelt’s victory, “There will come into power on March 4 a party with a new mandate from the people … The insecurity of the past two years will depart.”

C.M.R. also noted that year’s major realignment of the Senate, in which Democrats gained control and major Republican figures were forced out. The “change in the Senate … can hardly be said to result in less than the ‘new deal’ which Mr. Roosevelt called for so ardently.”

There wasn’t much more said in The Student’s pages about this election — most of the other articles focused on the inauguration of a new president of the college, Stanley King.

1868

In 1868, The Student’s founding year, former Union Army general Ulysses S. Grant won the presidency over Democrat Horatio Seymour. It was the first post-Civil War and post-abolition presidential election, the first in which Black Americans could vote in Southern states undergoing Reconstruction. In 1868, Amherst’s electorate and the nation’s were both all-male — women did not yet have the right to vote.

Grant received widespread support at Amherst, where The Student reported “Political Rejoicings.” After the election results were announced, the college was “illuminated”: “with the exception of the rooms held by those who are ‘totally mistaken’ in their political beliefs, every room in North, South, and East Colleges was illuminated” along with the library, President’s House, and faculty homes.

The college had not been lit up as such since 1854 at the inauguration of President William Stearns, and “it was a novelty to the people of the town as well of the students.”

A procession formed in front of Johnson Chapel and marched to the President’s House, where Stearns spoke, lauding Grant’s success in the Civil War.

“The occasion was a fine opportunity for certain members of the College to ventilate their exuberant spirits,” The Student reported.

Comments ()