Old News: Surveys and Soph Hops from November of 1928

Managing Features Editor Mira Wilde ’28, Staff Writer Sofia Angarita ’26, and Contributing Writer Shumona Bhattacharjya ’28 explore a November 1928 issue of The Student in this week's Old News.

Welcome back to Old News! In this column, we use a random number generator to select a year in the college’s history and take a look at The Student’s issue from this week in that year. Read more about this project in its first column here. For this week, we looked at the edition of the Student published on Nov. 26, 1928, four days after Thanksgiving in 1928, which featured issues that pressed the students of Amherst’s past: fraternities, a ban on student cars, and the Soph(more) Hop, amongst others.

Freshman Questionnaire

We used a random number generator to select our year for this week, 1928, after which we began searching in the November publications of that year. It was an exciting surprise to us when we stumbled upon the front page title: “Frosh Questionnaire Results are Compiled: First Poll of Its Kind Shows Many Interesting Facts About the Present Freshmen Class.”

Knowing that The Student had just published the results of its own first-year survey made us all the more interested in the answers. While we weren’t naïve enough to assume that a first-year survey was a novel idea, it was shocking to see that the first of its kind had been conducted nearly a century ago at Amherst.

Although the methodology of the survey has changed — the 1928 staff conducted their survey on paper after chapel service, while the 2025 staff used a Google Form — curiosity about Amherst newcomers remains a continuous interest of the paper. The 1928 edition of The Student featured two articles about the survey results: one that simply relayed the findings, and another, editorial-style piece that delved a little deeper and analyzed the possible impact of the questionnaire on Amherst campus culture.

The survey received responses from 152 out of the 196 members of the class of 1932. The survey questions asked three main things about the freshman class: 1) their time before Amherst, 2) the two months they’d spent at Amherst so far, and 3) what they envisioned their futures to be.

Over half of the respondents went to a “Prep School” — primarily private, elite, and rigorous academic institutions meant for preparing students for college, rather than public, non-preparatory high schools. In general, the class of 1932 averaged 4.1 years of pre-college secondary education. The majority of students (90) chose to attend Amherst because of its prestige, and just over one third (52) came because of relatives and friends at the school.

The Student also polled the incoming class on polarizing campus issues. For instance, only 46 freshmen supported the ban on all student cars that had started the previous semester.

The Student also asked freshmen about their opinions on fraternities. While the survey did not disclose how many students in the class of 1932 decided to rush a fraternity, it did find that three students regretted their fraternity affiliation and seven would not have accepted the bid of their current fraternity if they could rush again. The class was split on whether or not they favored the rushing system, with 83 students in favor and 76 opposed. Roughly a fifth of respondents (28) said that rushing had interfered with their studies. Fraternities were an ingrained part of the college, and although membership was not mandatory, for many members of the class of 1932, it was a crux of Amherst life.

In 1928, Amherst held mandatory chapel attendance, but began transitioning away from its mission as a Christian ministry college under President Alexander Meiklejohn, who served from 1912 to 1924. Despite this, religion remained an integral part of student life. In their 1928 survey, The Student asked about the religious affiliations of the freshmen class. While 136 students said college had not affected their religious affiliations, three students shared they were now more inclined towards atheism, nine towards agnosticism, and 11 reported “a firmer belief in God.”

For some, being at Amherst was a time to quit one specific behavior: smoking. Before college, 84 members of the class of 1932 reported smoking. But at the time of the survey, only 74 shared that they smoked.

Just as the culture remains in 2025, the classic rigor of Amherst College appears to have been alive and well in 1928. 89 students reported that their studies were more challenging than expected. Additionally, the class of 1932 reported spending over four hours per day on their studies outside of class based on averages of the responses.

Outside of the classroom, the class of 1932 was also interested in participating in “competitions.” While we might think of these as extracurricular activities or clubs today, Amherst students a century ago saw these as hierarchical and highly competitive groups. The top three competitions that received the most interest among the class of 1932 were 1) The Amherst Student (a stellar choice in our opinion), 2) being a sports manager, and 3) joining the Masquers — the school’s drama and theater club.

Concerning Expansion

As Amherst welcomed the new freshman class, the administration was inquiring about the increased size of the student body, which was part of a nationwide trend in higher education. For an anonymous editorial writer, expansion means “the student body is not made better but only larger.” This larger development, combined with student concerns about increasing class sizes and the strain on the college's material resources, encouraged President Arthur Stanley Pease, the 10th president of Amherst College, to appoint a faculty committee to investigate the issue at Amherst. The article reported that Pease presented the ramifications of student body expansion to the Board of Trustees. The report made two key recommendations: 1) the size of the entire college should eventually be reduced to 600 students, and 2) the class of 1932 should be limited to 200 students. In 1927, there were 767 undergraduate students (Amherst had a small number of master’s students at the time).

Pease expressed concern that the college’s physical spaces could not accommodate a greater student population, and increasing student concerns about popular courses imposing enrollment caps. These issues feel reminiscent of modern struggles with Amherst classes, such as trying to preregister for over-enrolled classes on Workday. In his report to the board, Pease argued that expansion would cause a more distant relationship between professors and students.

Arts and Entertainment

When it came to artistic endeavors, students from all class years were busy with their creative pursuits. In 1928, the Amherst Masquers’ Association was getting ready to put on an elaborate production of the comedy “Arms and the Man” by George Bernard Shaw. The Masquers Association was the first theatrical organization to “unite all branches of the college's dramatics.” The club built three sets of elaborate scenery for the production, which would take place on December 5 and 6, and they were apparently all historically accurate to the setting: 1865 in Bulgaria. Among the pieces being built were a Bulgarian stove and veranda.

After further research, we discovered the play is based on the Serbo-Bulgarian War of 1885 and centers on the gradual process of disillusionment with heroic ideals of love and war. Given that Amherst was putting this play on in 1928, it’s very possible that its themes reflected how this generation of Amherst students felt about war in the aftermath of World War I.

What stands out about the Masquers is that they were also the first theatrical organization to have women play female parts in their performances. For “Arms and the Man,” the three female roles — the young mother, the beautiful Bulgarian girl Raina, and the strong-willed servant — were all played by women from Mount Holyoke College. The ticket sales reportedly indicated that the performance would draw one of the largest audiences to witness a Masquers production yet.

Fraternity Glee Club

The Fraternity Glee Clubs were also gearing up for their December performance: the annual Inter-Fraternity Sing, where they would be competing for the 1902 Challenge Cup. By this point, the inter-fraternity sing had become an annual fall tradition that always “aroused keen competition.” The 1902 Cup was donated by members of the class of 1902 in 1927 to honor the 25th anniversary of their graduation. Each year, the winning group of the inter-fraternity sing would keep the Cup until the next competition, but the first fraternity to win three times would get to keep the Cup permanently.

Interestingly enough, the purpose of this competition was to revive the student body’s enthusiasm for singing — apparently, up until the event was established, Amherst seemed to be losing its love for song and falling short of its reputation as the “Singing College.” Nothing like a bit of fraternity competition to take care of that. The previous year, “Deke” (Delta Kappa Epsilon) beat the five other competing houses, singing both “Old Man Noah” and, surprise, surprise, “O Delta Kappa Epsilon.” The entire student body sang “Lord Jeffrey Amherst,” as was custom, while the judges deliberated.

For the 1928 competition, fraternities were set to sing “Happiness,” written by Professor of Mathematics Charles Cobb, followed by a fraternity song of their choice. The event was to take place on Dec. 10 in College Hall.

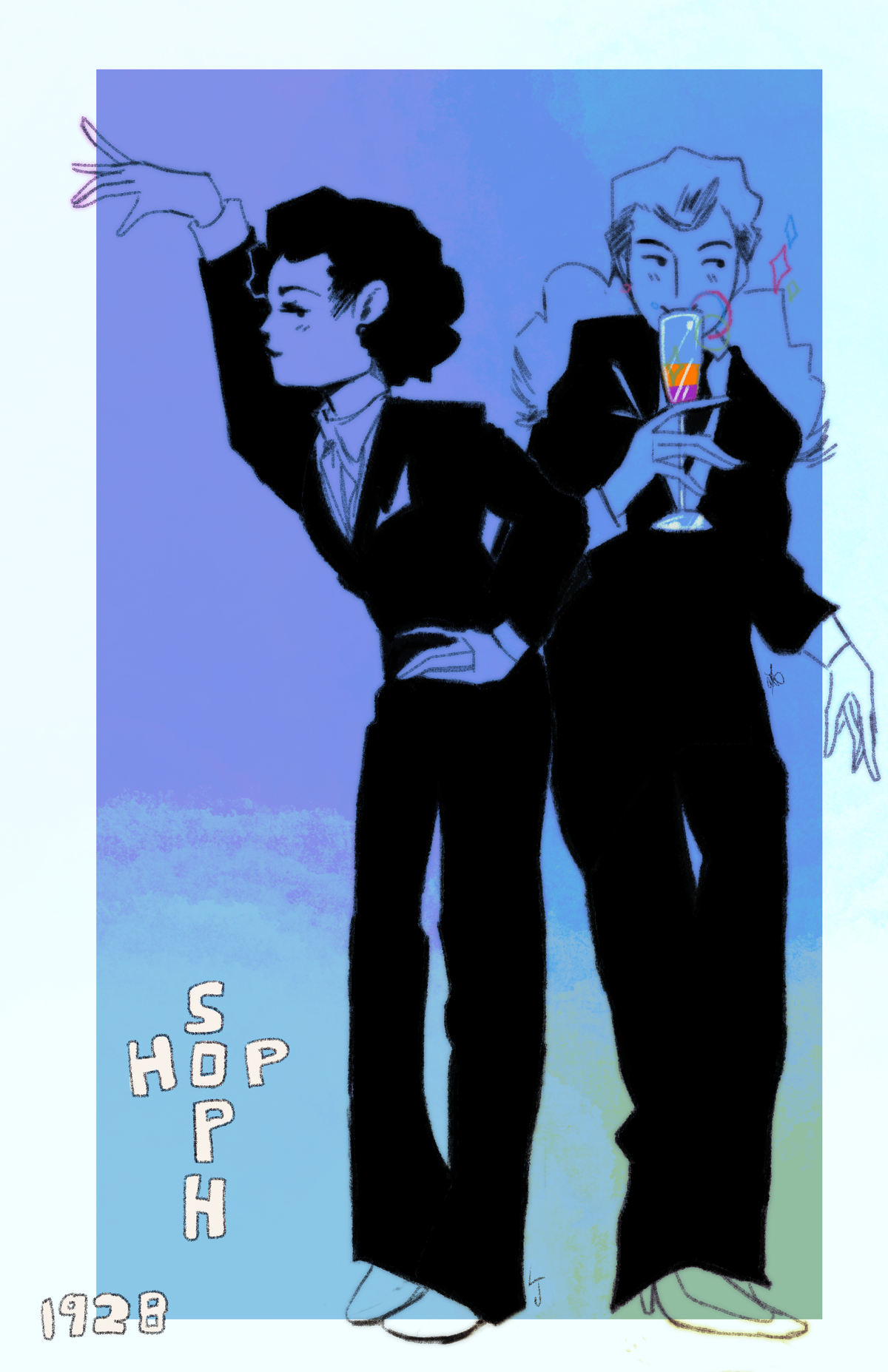

Soph Hop

For those of us who often find ourselves complaining about Amherst’s shortage of fun traditions nowadays, this edition shows us yet another one that we sophomores are now missing out on — Soph Hop! Around this time of year in 1928, preparations were being made for the sophomore dance, although somewhat surprisingly, the planning committee was “disappointed at the lack of response exhibited by the student body.” At the time this article was published, fewer than 70 men had signed up to bring women!

Nonetheless, it looks like the Soph Hop was to be quite the lavish event. An organization called “Bias of Amherst” was responsible for catering, and Mal Hallet’s orchestra was to provide musical entertainment. Mal Hallet was apparently quite the big name — in fact, his jazz ensemble was among the most prominent in New England at the time. No specific details were given about decorations, as negotiations were apparently still in progress, but I’m imagining full ballroom dancing attire. Who knows, maybe this is our sign to bring back Soph Hop!

Afterthoughts

A column titled “Afterthoughts,” signed by the initials R.T.R., features a poetic reflection on a hockey game in Springfield and America’s relationship with sports. The section uses miniature drawings of “The Thinker” by Auguste Rodin as bullet points for each thought.

The column begins: “A large indoor hockey rink; stands for several thousand people; crowds milling about between periods, talking loudly or consuming quantities of hot dogs and rank coffee; air heavy with smoke so that the flood lights seem to breathe forth a brilliant haze of illumination.” R.T.R. reflects warmly upon familiar game dynamics: referees attempting to control unruly players, crowds demanding “more disorder” and less referee intervention, hassling the referee, and the breakout of player on player fights.

R.T.R writes that America is a “sport-loving nation,” comparing it to Rome and gladiators. The author advertises a nearby local game: “Drop down to the next hockey game in Springfield.” They elaborate on this advertisement: “It will be a delightful evening, perhaps a player will get his head broken by a hockey stick; perhaps there will be a riot. The possibilities are endless.”

The author calls for a continued love of sports, but their attitude towards violence in sports appears puzzling. Despite having described broken heads as part of a “delightful evening,” they praise the decency and sportsmanship of college crowds and conclude: “A rule should be passed immediately to the effect that any undergraduate who emits even a faint cat-call at an opposing team shall be straightway hanged.”

Advertisements

There seemed to be two main themes amongst the featured advertisements: 1) Thanksgiving, and 2) Where the incoming class (and those returning for the academic year) should look to find their essentials — transportation, cigarettes, clothes, and so on.

One company found a way to combine the two themes to market their clothing: “A well-dressed young man reflects the prosperity he feels, and radiates his thankfulness in Braeburn University Clothes.” The College Candy Kitchen, a former restaurant in Amherst, advertised that they would be open all day Thursday, in addition to serving a special turkey dinner.

One advertisement targeted students (particularly those scared about life after graduation) directly: “Will you be prepared for business leadership?” This initial question was followed by even more intense fear-mongering questions. “When you finish college, will you have a knowledge of business fundamentals that will enable you to succeed? Or are you facing years of apprenticeship — the trial and error method — which may never lead to success?” Fortunately, the Babson Institute offered the perfect training to aid with the transition from college life to the business world in a nine-month program.

Other advertisements appealed to students through humor that was specifically tailored to them. The Shredded Wheat company advertised: “Notwithstanding the Profs, you can retain your eligibility or your good scholastic record more easily when you feel wide awake and energetic. There’s plenty of roughage and bran to assure this in Shredded Wheat,” followed by the simple slogan “Eat it With Whole Milk.” This ad invoked academic anxieties, arguing that the proper fuel gives students a better chance at success in school. Shredded Wheat actually still exists today — Kellogg’s Frosted Mini-Wheats are a common modern example.

The 1928 Frosh questionnaire indicated that almost half of the freshman class smoked, and advertisements reflected the continued popularity of tobacco. An ad titled “Army Man Find Tobacco ‘Like Old Friend’” showcases Edgeworth Extra High Grade Smoking Tobacco. Signed by E.H. Fulmer, the ad discusses the point of view of a fictional character who would rather wait for high-quality tobacco — as one waits for the companionship of an old friend — than use poor quality products that "punish my throat and lungs and nostrils with inferior grades.”

On Nov. 26, companies began preparing for the Holiday Season. James A. Lowell Bookseller advertised (Personal Christmas Cards). Some of the cards simply displayed “college views” and “snow scenes.” Their most special service, however, was the chance to have them develop your own film camera negatives into a personalized Christmas card.

The arts were also present in the advertisements. Amherst Theater, which is now Amherst Cinema, was set to screen the two-reel comedy (approximately 20-minute-long short film) “Revenge” on Nov. 26 and 27. Dolores Del Rio, who previously starred in “Resurrection” and “Ramona,” was now set to play the “turbulent, dashing spitfire maid of many moods!” Del Rio was the first major Latina actress to be popular in mainstream Hollywood: A must-watch for all Amherst cinephiles of the 1920s.

Ultimately, reading The Student from November 1928 feels less like looking into the past and more like overhearing an earlier version of the same conversations students are having now. From first-years puzzling over their place on campus, students debating expansion and identity, clubs competing for attention, and a community inventing new traditions while letting others fade — the details may have changed, but the impulse to define what Amherst should be has not.

Comments ()