Revisiting Shakespeare: The Tragedy of “King Lear”

In this week’s “Revisiting Shakespeare,” Senior Managing Editor Edwyn Choi ’27 reviews the technical complexities and perplexing plot lines of “King Lear.” Despite controversial critiques and adaptations of this popular play, there are still intense themes Choi finds worth exploring.

“Thou art a soul in bliss, but I am bound

Upon a wheel of fire, that mine own tears

Do scald like molten lead” (4.7).

“Chaotic” is the first word I’d use to describe “King Lear” — Chaotic, yet somehow beautiful. This centuries-old tale of intra-familial violence, suffering, and love contains some of William Shakespeare’s best poetry but, to me, is also the least structurally sound of his major tragedies. To quote 20th-century scholar A.C. Bradley, “[‘King Lear’] is therefore Shakespeare’s greatest work, but it is not … the best of his plays.” In fact, its multitude of subplots and ensemble cast are so large in scope that it was once considered unperformable. Its ending is so bleak that Shakespeare’s original text was replaced for 150 years with a more optimistic version, Nahum Tate’s “The History of King Lear.” Among other things, Tate’s play kept Cordelia alive and returned Lear to his throne (both of whom are killed in Shakespeare’s text).

Despite these apparent faults, we still read and perform this play to this day, perhaps because we’re willing to forgive its technical faults for its emotional height.

“King Lear,” like many venerated classics, is first and foremost about property and inheritance. Growing old, Lear has “divided / In three [his] kingdom,” between his daughters Cordelia, Regan, and Goneril. Each daughter’s share of the kingdom will be determined by how much praise they can give to Lear, “That we our largest bounty may extend / Where nature doth with merit challenge.” But there are hints that things have already been finalized on paper, suggesting that this “love test” is largely ceremonial, or simply for Lear’s emotional validation. Regan and Goneril flatter their father to the best of their ability:

Goneril:

“Sir, I love you more than word can wield the matter,

Dearer than eyesight, space, and liberty,

Beyond what can be valued, rich or rare,

No less than life, with grace, health, beauty, honor;” (1.1).

Of his third and favorite daughter, Cordelia, Lear asks, “What can you say to draw / A third more opulent than your sisters’?” “Nothing,” Cordelia answers. This is where we get one of the play’s most famous lines in the form of Lear’s retort: “Nothing will come of nothing.” He soon begs Cordelia to “Mend [her] speech a little, / Lest [she] may mar [her] fortunes.”

But Cordelia doesn’t budge, explaining that she doesn’t need to flatter Lear like her sisters did if she truly loves him. Hurt by Cordelia’s honesty, Lear banishes her from his kingdom, disowns her, and divides her share of the family fortune between Goneril and Reagan. Lear also strips Cordelia of her dowry, but one of her suitors, the king of France, still decides to marry her for her honesty.

Lear’s division of his kingdom also included an expectation that he would be allowed to live with his daughters in rotation. However, his rowdy behavior and his retinue of 100 knights are “so disordered, so debauched and bold, / That this [Goneril’s] court, infected with their manners, / Shows like a riotous inn.” Regan isn’t very accommodating, either, and both daughters insist that Lear must cut his retinue by at least half: “How in one house / Should many people under two commands / Hold amity?” Enraged by his daughters’ supposed disobedience, Lear runs away into a brewing storm. Later learning that their father could become a political threat by reuniting with Cordelia and the French king in order to take back his kingdom, his daughters (along with Regan’s husband, the Duke of Cornwall) declare war on France, turning the family drama into a political conflict.

Simultaneously, there’s a separate plot involving one of Lear’s advisors, the Duke of Gloucester, and Gloucester’s illegitimate son, Edmund. Edmund hatches a plan to take power for himself, which involves pitting Goneril and Regan against each other as well as betraying Edgar (his half brother) and Gloucester. Gloucester’s political downfall roughly parallels Lear’s descent into madness, and as the play moves towards England’s war with France, the Lear subplot and the Gloucester-Edmund-Edgar subplot converge … or just crash into each other.

If it wasn’t clear already, there’s a lot going on in the play — maybe a little too much. Trying to understand the two plots alone on a first viewing is a difficult task. Then, there are plot holes and inconsistencies that make “King Lear” feel like a rushed first draft (for those who are interested in a near-exhaustive list of the play’s major technical flaws, A.C. Bradley’s 1919 collection of lectures, “Shakespearean Tragedy,” is a good place to start). That’s on top of the fact that there are at least 10 major character roles to keep track of, including the Fool and Earl of Kent, whom I haven’t mentioned but are important to the play overall. This multiplicity makes “King Lear” different from Shakespeare’s other tragedies, like “Macbeth” and “Othello,” whose plots focus on two to four central characters.

Moreover, “King Lear” is one of Shakespeare’s bleakest plays (though we can’t forget the brutality of “Titus Andronicus”). Everyone but one or two of the side characters dies in a fashion typical of Shakespearean tragedies, but this is only after Gloucester’s eyes are gouged out onstage and the major characters suffer at a Christ-like intensity. In other words, experiencing “King Lear” is a difficult endeavor, not only due to its scope and relatively flimsy construction, but also because of the sheer brutality and pain that infects its ensemble cast.

But this focus on suffering is what distinguishes this play from Shakespeare’s other works and very well might make up for its technical issues. Few of his plays focus so much on the meaning of suffering, with Gloucester at one point observing, “As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods; / They kill us for their sport.” This is to say that the characters suffer an almost random, meaningless suffering, and yet still try to create meaning out of their pain: “Why should a dog, a horse, a rat have life, / And thou [Cordelia] no breath at all?” The play’s bleak ending suggests that the universe of “King Lear” does not care about justice — characters who arguably deserve to stay alive are killed (which was one of Tate’s gripes with Shakespeare’s text when he was rewriting the play).

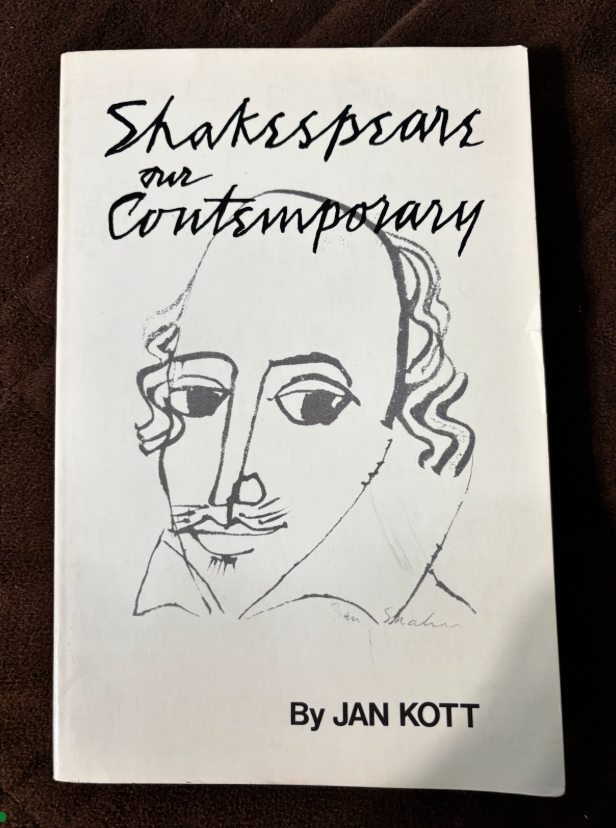

This focus on the absurdity of suffering in “King Lear” has garnered the attention of many scholars, especially in the mid-20th century, when absurdist fiction (Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s “The Visit,” etc.) had taken over the theater world. Following the horrors of World War II, this movement was focused on the human struggle to establish meaning in a seemingly meaningless universe. Jan Kott’s influential 1961 essay, “King Lear and Endgame,” uses absurdist theater (mainly Samuel Beckett’s “Endgame” and “Waiting for Godot”) to reinterpret “King Lear” as a work of absurdist art.

For those interested in watching Shakespeare instead of reading his work, do not fret: “King Lear and Endgame” inspired English director Peter Brook in 1962 to direct his absurdist “landmark production” of the play, first onstage and later as a film adaptation (available for free on YouTube). But this push toward making Shakespeare modern didn’t come without some backlash, which Maynard Mack examines in his 1965 book, “King Lear in Our Time.” Another essay, which I’ve been recommended by both professors and more casual followers of Shakespeare, is Stanley Cavell’s 1969 essay, “The Avoidance of Love: A Reading of King Lear,” which approaches the play’s so-called universal themes of suffering and love from a philosophical perspective.

There are too many “King Lear” adaptations for me to cover them all here, and they’re equally as complex and fascinating as Brook’s work was. But some “canon” adaptations that must be mentioned include Grigory Kozintsev’s 1971 film adaptation, “Korol Lir” (“Король Лир”), and Akira Kurosawa’s 1985 samurai film, “Ran” (“乱”). They are available on YouTube and Kanopy, respectively.

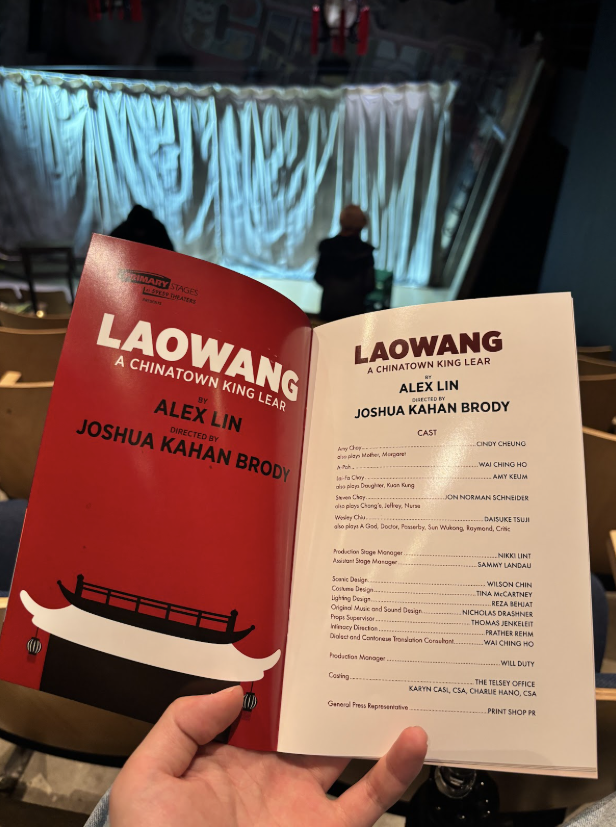

On the note of Kurosawa's film, “King Lear” has garnered a lot of interest in East Asia, becoming the subject of many Taiwanese, Japanese, and South Korean theater productions in recent decades (one could teach a class just on Japanese “King Lear” adaptations alone!). There are adaptations that are being performed now, such as Alex Lin’s off-Broadway “Laowang: A Chinatown King Lear,” which will continue its run in Manhattan until Dec. 14.

As for literary texts, one major work is Jane Smiley’s 1991 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “A Thousand Acres” (granted, there is a film adaptation, but I hear it’s bad), while a more recent book is Julia Armfield’s 2024 “Private Rites.” However, I also can’t help but recommend some Lear-adjacent stories that touch upon themes of suffering and familial relationships: Sophocles’ “Oedipus Rex”; the Bible’s Book of Job; Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1880 novel, “The Brothers Karamazov”; and HBO’s “Succession.” I’ve been told that “Oedipus Rex,” “King Lear,” and the Book of Job are all taught in sequence in Samuel Williston Professor of English Geoffrey Sanborn’s class, “Narratives of Suffering,” which will be offered in Spring 2026.

While “King Lear” certainly doesn’t have the polish or neat construction of “Othello” or “Julius Caesar,” it hits an emotional rawness and intensity that’s unrivaled by anything else Shakespeare wrote. I’m willing to accept its technical flaws for its examination of pain and suffering; but for days when revisiting “King Lear” feels rather boring, however, there’s still a breadth of scholarly work, adaptations, and even Lear-adjacent work for me to turn to.

Comments ()