Robert Morgenthau at Amherst: Going Out with an Epoch

Managing News Editor Leo Kamin ’25 explores the fraught and foreboding college life of legendary alum Robert Morgenthau ’41, a Jewish student who went on to serve as Manhattan’s longest-serving district attorney.

Robert Morgenthau ’41 was one of Amherst’s most legendary alumni. As Manhattan’s longest-serving district attorney, from 1975 until 2010, he prosecuted John Lennon’s killer, sent Tupac Shakur to prison, and was described as “the scourge of white collar criminals.” His proteges included Sonia Sotomayor, Andrew Cuomo, and Eliot Spitzer.

But when Morgenthau arrived as a freshman at Amherst in the fall of 1937 he was an 18-year-old who had “never taken to books,” writes Andrew Meier in “Morgenthau: Power Privilege, and the Rise of an American Dynasty.” In those days before week-long orientation, his mother dropped him off and promptly left town. Bob, as he was known to his friends, took his first meal alone, dropping his trunk in Morrow and heading to a Greek restaurant in town.

Over the next four years, Morgenthau, who was Jewish, would thrive on a campus still rife with antisemitism, becoming president of his fraternity, the chairman of The Student, and the founder of the Amherst Political Union (APU). Meanwhile, the world marched steadily toward war, a reality that Morgenthau and his classmates increasingly could not ignore.

Morgenthau was, in every way but one, the perfect “Amherst man.” He had been educated just up the road, at the prestigious Deerfield Academy. He was 6 feet tall and had been a multi-sport athlete in high school. And his father, Henry Morgenthau Jr. was the United States secretary of the treasury.

But Morgenthau was also Jewish, one of only five Jewish students in his class of 240. His arrival was just 40 years removed from that of the first Jewish student at Amherst: Mortimer Loeb Schiff, a descendent of two different prominent New York banking families. In “Amherst in the World,” Lecturer in American Studies Wendy Bergoffen details the antisemitic suffering Schiff endured at Amherst. In one account, Alfred Stearns ’1894, of Stearns Hall, remembered that “his favorite pastime ... was to eject Mortimer Schiff from the room.” Schiff’s classmates would pick him up by his four limbs and dump him in the hallway. He nevertheless became a prolific donor to the college.

The atmosphere of open exclusion of Jews continued even into the 1930s. Jewish alum E. Ernest Goldstein ’1939, just two years Morgenthau’s senior, said that Amherst “provided the sole, and unforgivable, experience in my life of being treated as a second-class citizen.”

As a prep school graduate who had spent his childhood summers sailing with the Kennedys, Morgenthau was likely better prepared than many of his Jewish peers for Amherst’s social climate. The obstacles were still there, though. His headmaster at Deerfield had told him that membership in a good fraternity was the key to college success, but Amherst’s oldest and most well-regarded frat — Alpha Delta Phi — had never had a Jewish member.

“Alpha Delt” was founded in 1837, when the college’s mission was still largely ecclesiastical. In a 1950 book on the college’s architecture, former college president Stanley King ’1900 located the origin of the the fraternities in the fact that “even the young men who were attending college in preparation for the Christian ministry had their normal share of high animal spirits which were not entirely sublimated by chapel services at five in the morning.” By the 1920s ands 30s, Bergoffen writes, “fraternities shaped life outside the classroom, including where students studied, dined, and slept.” And though the college no longer prepared men for Christian missions, most fraternities rarely accepted Jews.

That social stigma would ultimately meet the overwhelming force of Morgenthau’s connections. Fellow Deerfield and Amherst alumni were enlisted to make his case, and the matter was subjected to a vote. This was no small matter: powerful figures such as Former Republican Governor of New York Charles Whitman ’1890 made it clear that they opposed Morgenthau’s bid. In the end, Meier writes, the endorsement of Deerfield alumni and the school’s headmaster won out. Morgenthau was the first Jew to be an Alpha Delt.

It would be a mistake to see Morgenthau’s experience as marking some breakthrough for Jews at Amherst in general. The Morgenthau family was fantastically wealthy and intimately connected to political power. Bob’s social successes were “certainly an exception,” Bergoffen writes. For everybody else, this was a period in which “as intellectual doors opened … social doors closed.”

It is worth noting that religious and ethnic background was not the only gulf between Morgenthau and his Alpha Delt “brothers.” Meier writes that Amherst had long been a “Republican reserve” in those days when the Northeast’s economic elite were firmly committed to the Grand Old Party.

The Morgenthaus, instead, were Democrats. Robert’s father, Treasury Secretary Henry Jr., was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s closest confidant within the cabinet. His grandfather had been Woodrow Wilson’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. The animosity toward Democrats, and Roosevelt especially, ran so deep within Alpha Delt that Henry Jr. decided not to attend his son’s initiation. “He had no wish to rile the alumni,” Meier writes.

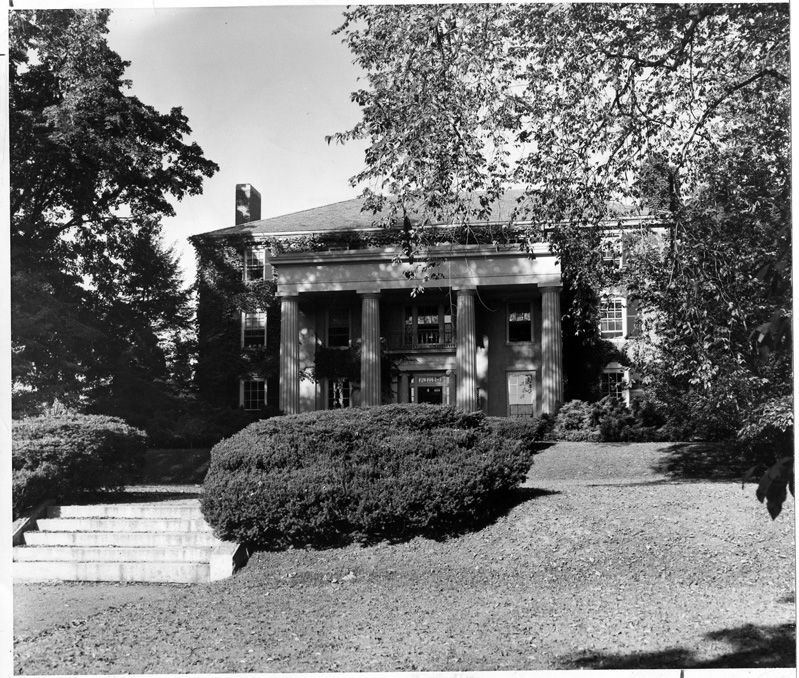

The younger Morgenthau, though, was used to running in heavily Republican circles. He easily ingratiated himself with the fraternity’s current and former members, and the Alpha Delt house (today’s Hitchcock House), became the center of his college experience.

Morgenthau quickly made his mark on the house. In the summer of 1934, a seventeen-year old Morgenthau shot a 200-pound bear while hunting in Montana. (The haul was announced in the Daily Jewish Bulletin: “Morgenthau’s Son Bags Grizzly on Montana Vacation”). In the fall of 1938, the grizzly, now stuffed, was placed in a position of prominence next to the fireplace in the Alpha Delt house.

As Morgenthau settled in at Amherst, joining The Student, founding the APU, and taking up positions in student government, the world careened towards war. Though Morgenthau had “never taken to books” prior to Amherst, Meier writes that he became increasingly interested in current affairs during his college years. Germany’s annexation of the Sudetenland came in the fall of his sophomore year, the invasion of Poland in his junior fall, and the blitzkrieg invasions of France and the Low Countries the following spring. The growing sense that the U.S. was destined for war hung over much of Morgenthau’s work at Amherst, from the events he organized for the APU, to the editorials he ran in the student, to his task as the editor of the 1941 Olio.

Morgenthau and his classmates had a keen interpreter on hand as Hitler drove the world towards calamity: Karl Loewenstein, a German law professor with Jewish ancestry, fled Munich for Amherst in 1933, eventually becoming chair of the political science department. Having watched Hitler dismantle the fledgling Weimar republic, Loewenstein dedicated much of the rest of his career to analyzing the way in which democracies can devolve into dictatorships, coining the phrase “militant democracy.” Morgenthau took “Elements of Modern Politics” with Loewenstein his sophomore year, staying after on at least one occasion for a “long talk.” In a letter to Henry Jr. quoted by Meier, Loewenstein confessed that, in class, he had to “conceal some deep misgivings about the future of democracy and the world.”

In The Student and elsewhere, Morgenthau expressed similar sentiments. Editorial after editorial published during Morgenthau’s tenure as editor-in-chief make note of the ongoing war in Europe and the increasing probability of American involvement. One, titled “If War Comes” and published on March 4, 1940, decries the apathy of a student body committed neither to energetic patriotism or idealistic, well-defended pacifism: “The primary ethical problem is a potential one: What is to be the stand of young Americans in the event of American entanglement?” it reads. “Most of us have given it no thought whatsoever ... Are we not drifting, pitiably oblivious, in a moral vacuum?”

Beyond these editorials, though, the pages of the Morgenthau-era Student are still mostly full of the everyday concerns of the college. Students engaged in lively debate over whether the pledging period for fraternities should take place before or during the school year and whether or not hazing ought to be banned. Also at issue was the college’s relation to its Christian past: in the March 18, 1940, issue, the editorial board came out against the continuance of mandatory chapel attendance.

For Morgenthau, foreboding coexisted with classic college antics. As Laura Turner ’08 reported in The Student in 2004, Loewenstein was Morgenthau’s interpreter of fascism, but he was also the referee in a beer-drinking contest Morgenthau organized and subsequently covered in The Student. The article was pivotal in his appointment as Student chairman.

However, by Morgenthau’s senior year, “the war overseas had consumed him,” Meier writes. While still in college, he joined the Naval Reserves, putting him on track for potential officer duty. And though the family was thoroughly assimilated and not religious, Morgenthau had come to a “new consciousness of his Jewishness” through his obsession with the plight of Jews abroad; through his father, he requested copies of the government on the number of Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler. In February of 1940, he invited Eleanor Roosevelt, a close friend of his mother, to speak to the APU. She, too, could speak of nothing but the war in Europe and the possibility of American involvement.

It is clear that Morgenthau came to see college life — the sports, the student committees, the fraternities — as a tranquil and somewhat unreal interlude before he and his classmates were subjected to the harsh realities the real, war-torn world.

One lyrical Student editorial published while Morgenthau was chairman (perhaps penned by future Pulitzer-Prize winning poet Richard Wilbur ’42?) conjures the mindset of students in Morgenthau’s time, presenting a night out at Amherst as a temporary joyful prelude to the dark realities of the world

“Tonight the better part of Amherst’s sons will clasp hands with some maenad Alice and take a header down the rabbit-hole of hedonism. They will ... drink the little bottle from the table, and, the world grown miraculously large and dim, enter for a while into the garden of wonderland.

In this bright wonderland there is no rattle of Lewis Guns, but the pleasant racket of ice in the shaker; no menacing totalitarian mandibles, but the smiles of pretty maids. … Never before have young men so seriously required this yearly journey into oblivion …

For the world is grown too big for all but the strong, and even the strong must succumb to gentle unreality now and then. The door to wonderland is here, and the key and the little bottle are on the table. Drink it, gentlemen, drink it.”

In the spring of 1941, with the Nazis in control of much of Europe and American entry into the war all but assured, Morgenthau saw his Amherst as a world that might soon cease to exist. He said as much in the valedictory letter he wrote as editor of the 1941 yearbook. “The class of 1941 has the bitter-sweet satisfaction of knowing that it goes out with an epoch,” he wrote.

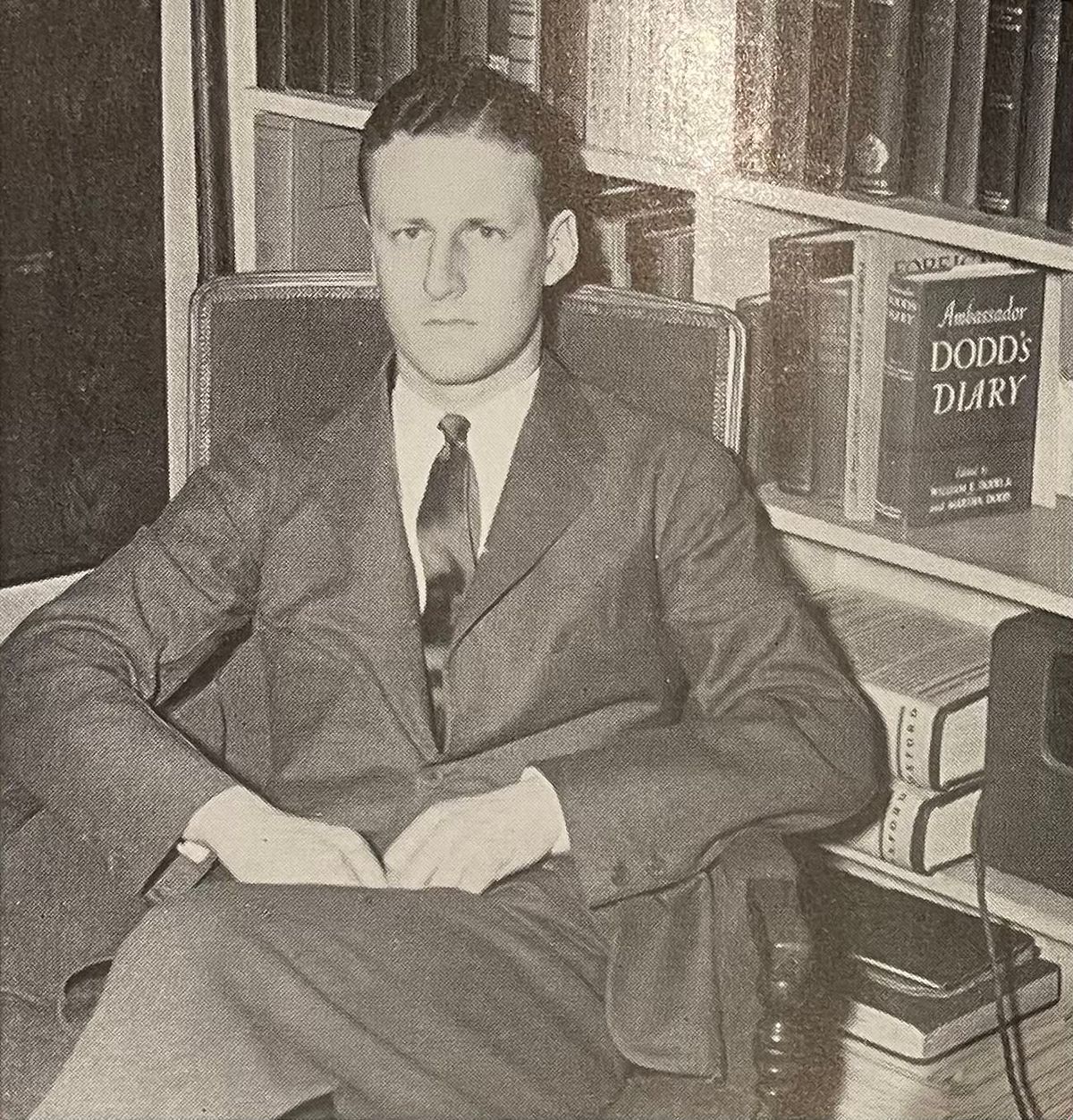

That yearbook displays both his remarkable achievements at Amherst and his sense of foreboding. As chairman of The Student, president of the APU, president of Alpha Delt, and member of the Committee of Seven, he is pictured time and time again at the front and center of a large group of suit-clad men. In each photo, he stares directly into the camera, ultra-serious. He never smiles. His eyes are those of someone who knows what is coming.

Robert Morgenthau joined the Navy as an officer in the fall of 1941. He eventually served on destroyers in both theaters of the war. He lived through the sinking of his ship at the hands of German bombers in the Mediterranean and Kamikaze attacks in the Pacific. He survived the war to pursue an unparalleled legal career in the public service; he died in 2019, just 10 days short of his 100th birthday. Many of his classmates were not so lucky. 108 Amherst alumni died in the Second World War.

As he signed off as Olio editor in the spring of 1941, Morgenthau foresaw this carnage. In the valedictory letter, he made reference to the town where the Greeks beat the Persians in 480 and the Germans had just beat the Allies in 1941. The beautiful final sentence reveals so much about Morgenthau — his gift for writing, his vision of the future, and the way in which even a Jew as connected as he was nevertheless had to subtly conform to the Christian world.

“As the last year draws to a close” he wrote, “the Greeks and British have fallen at Thermopylae, America stands not far from Armageddon, and the class of 1941 prepares to do battle for the Lord.”

Comments ()